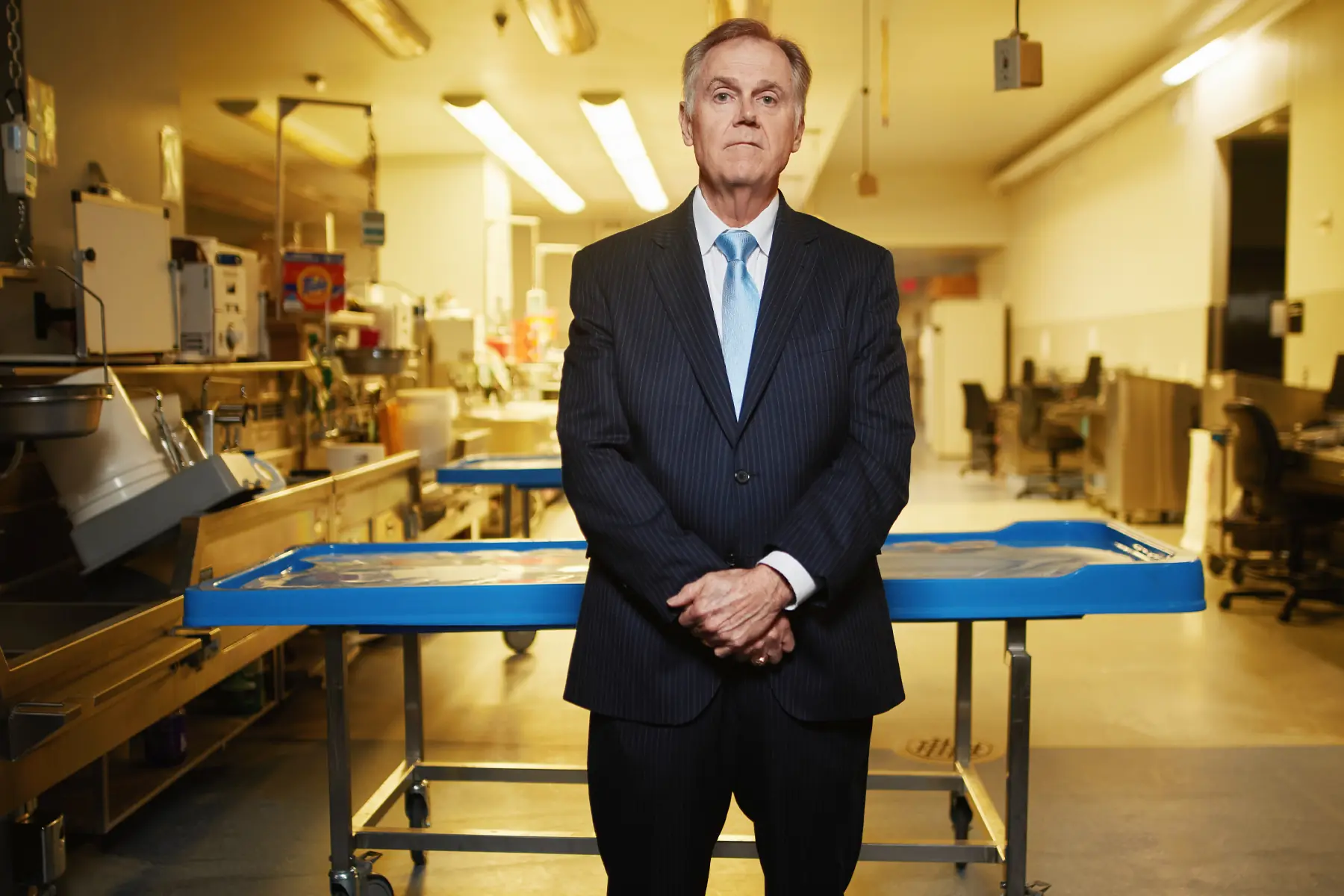

In 1991, Dr. Jeffrey Barnard became the second chief medical examiner in Dallas County’s history. He was only 35 years old. This November, he will retire after 33 years of leading the Dallas County Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences, which is responsible for autopsies but also has laboratory capabilities that have resulted in significant progress in DNA and drug testing.—As told to Matt Goodman

“When I started, there was a chief, a deputy chief, three medical examiners, and two fellows. Now we have a chief, a deputy chief, 12 medical examiners, and two fellows. And we put our fellows to work. If you train here, you can go anywhere. We had a total of just under 4,000 cases in 1987, of which we autopsied about 1,900. That’s about half. We just didn’t have the manpower to do more. In 2022, which was our highest number of deaths, we had a total of 5,885 cases, and we autopsied 4,797. A rate of 70 percent to 80 percent is what I shoot for. Another goal I have is that we not only serve Dallas County but all these counties surrounding us that don’t have the option of a medical examiner. There are no better training opportunities than the cases that come out of East Texas. They’ll shoot them, they’ll set them on fire, they’ll bury them. These are very complicated cases, the type of work some people never get in their careers.

“Every unnatural case needs to be autopsied, as do many natural or possibly natural cases. We tend to take on cases other offices might not; we don’t want questions to go unanswered. Laziness is not a virtue. So, yes, we see the homicides, the high-profile deaths. We also see what I call the tenuousness of life. How many people got up one morning, but they never made it through the full day? They either collapse from natural disease, or they’re driving their car and someone runs a red light and T-bones them. I try to explain this to people: don’t go to bed mad at each other. What if something happens the next day, and it’s your spouse or your parent?

“Our job is to represent and protect the public. These are my patients, so to speak, and we are answering questions about their natural or unnatural deaths. That’s our role. Those answers effect public safety, almost every time. Even if it’s a heart attack case, that becomes, on a grand scale, what is the risk of heart attacks? What if this is a 25-year-old who has cardiac disease? Well, that’s important. Certainly the family has a vested interest in that information. Are there more car wrecks occurring on a certain road? What is it about that road?

“Looking back through my logbooks, fentanyl cases started popping up around 2003. Its rate started to shoot up a few years later, and in the last few it’s been high. But we saw that coming early because we can test blood drug concentrations to the nanogram. Having the drug lab enables us to identify drugs that begin to be seen in our autopsies. Take the cheese heroin crisis, which killed about 30 kids in the mid-2000s. We had to tie together that we had two drugs and that they’re actually combined. Acetaminophen? Well, that’s just Tylenol. But when it’s Tylenol mixed with the heroin, that becomes more significant. That’s the value of having a director who’s a physician and able to communicate that what they’re seeing could have implications for what authorities and public health officials need to know. Overdoses often pop up in clusters. We can trace that, which helps with identifying distributors.

“I did a lot of jigsaw puzzles when I was a kid. Solving a puzzle is always fascinating to me, and that’s basically every single case—a puzzle. That’s why it’s important that we have the Southwestern Institute of Forensics. I’m proud of our work in the forensic DNA laboratory. Before I arrived here, our office had a policy that we store any DNA evidence we can. A lot of other public crime labs, including some police departments, either discarded or lost that evidence because there was no forensic DNA testing in criminal investigation labs back then. But because we kept so much of it, we’re able to prove that an innocent person had been convicted for a crime they didn’t commit. And sometimes it proves it was the right person. That’s all valuable; it answers the question.

“When the district attorney’s office began using DNA to exonerate the wrongfully convicted, it was our evidence that made those cases. But we don’t work for the prosecution. We work for the person who died. It’s a horrible thing for an innocent person to be convicted. I like to go back through our logbooks to find patterns, look at cold cases. In the 1980s, for instance, we found several elderly women who had been murdered in Oak Cliff. Those were unsolved murders. The families never found closure.

“When I came here in 1987, I remember one of the medical examiners saying that there was a serial killer who was killing older people in Oak Cliff. I remember doing an autopsy on what I thought was one of those victims in 1988. You didn’t have any technology. You could find their semen, but that’s about as far as you could go. You couldn’t go further in analysis. Once our technology started advancing, and the feds created a DNA database that allowed us to compare our sample with others across the country, I went through the old logbooks and manually found cases I thought might be of value to investigate.

“There are no better training opportunities than the cases that come out of East Texas. They’ll shoot them, they’ll set them on fire, they’ll bury them.”

“I thought, maybe there is a link between those killings. Maybe we can lock this in to one serial killer. We went back to one of the cases, from 1985 or 1986, and we got a profile from the semen. Then I went back through evidence from those others, and none of them linked up. I don’t know what’s worse, that there’s a serial killer killing many or many killing individuals. We were able to match profiles on two of those cases. One, the suspect had died. But the family called me to thank me for not forgetting about her. The case for the other, a woman named Mary Hague Kelly, will be going to trial the Monday after I retire. That’s because of our DNA testing and the advances in DNA technology.

“Of course, we’ve had to manage many mass casualty cases. You focus on what’s in front of you. You focus on each case, you make your notes, you dictate what you can, then you move on to another. The 1991 Luby’s shooting in Killeen, all those bodies came here. Back then, there were people saying, we don’t need to collect all that evidence. Yes, we do. The justice of the peace in Bell County only wanted to send the shooter. I convinced him to send everyone. Pay the money, let us do the work, catalog the bullets. We had all the bodies on refrigerated trucks in our parking lot.

“Later on, the questions came up: they’re accusing the police of having shot people in the Luby’s as they’re trying to get to the shooter. Because we did the work, because we handled each of those deaths like it was the only case, we could answer that question. The explosion at the fertilizer plant in West, those victims came here. The July shooting downtown, we handled those, too. I did the shooter’s autopsy, where he was killed by a bomb that had been attached to a robot. That was the only time I was able to put on a death certificate the word ‘robot.’ In forensics, you don’t have a lot of funny moments; I thought it would look weird when I wrote that word, but that’s exactly what it was.

“But in this business, your merit is not based on whether you can do a high-profile case. If you can’t do a high-profile case when everyone’s watching, you shouldn’t be doing this. I’ve had a mantra as long as I’ve been doing this work. The merit of how good you are is dependent upon how you handle the cases no one seems to care about, the people whom society looks down upon, the homeless, the drug addicts, the alcoholics. I don’t call them ‘throwaway people,’ but that can be the way the public looks down on them. Those are people, too. Those are my patients. If they’re not going to be cared about by anybody else, they’re going to be cared about by me. Those are the cases who define who you are.”

This story originally appeared in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline “I See Dead People.” Write to matt.goodman@dmagazine.com.