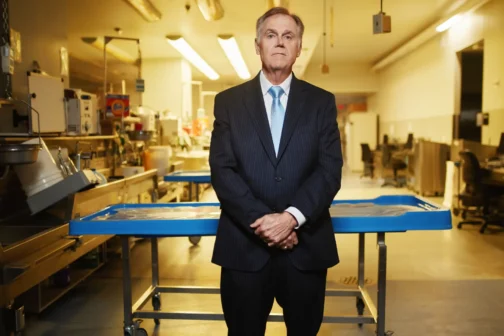

“I’ve been doing this about 30 years. For the first 15 or so, it was all about getting cheaper pricing and teaching people how to talk the lingo. But as time went on, I just started realizing how the death care industry separates us from a very basic need, and that is to take care of our own dead. You know, we hug babies, we hug people. We get close to them, we smell them, we’re involved with them as they grow. And as they die, we visit them in the hospital, and we get close to them. Then when they’re dead, all of a sudden, the system sucks that body out of there.

“You get a look at them at the viewing, and they’re all puffy. They look like the Marshmallow Man, you know, embalmed. And then the box gets closed. Three or four days from the time a person’s dead to in the ground, you’re going through this huge range of emotions, and you don’t have anything to do. You’re just sitting around eating potato salad and pizza, and you’re hurt.

“But if you do it yourself, yes, it’s a little messy. And for the first five minutes, you think you made a stupid decision. But from that point on, you’re involved. And as you’re involved, you’re working through the process. You’re going from that live person, and you’re walking their journey with them.

“I guess the most profound thing with my brother and I was it took four days to get Dad in the ground. And of course, we were around his body all the time, but it took four days for his body to completely go to rest. He went through the rigor mortis at first, and that’s part of it, to experience that, because that’s the body fighting death. So to actually see it is good. And about noon on day four until 4 o’clock, when we got him in the ground, we saw no change, so we knew for sure that his body was completely at rest and that we were going to put him in a hole in the ground in the Texas Panhandle where he could rest in peace. So those phrases mean something to us now.

“Being raised by a man who grew up in the Depression and the Dust Bowl out there in the Panhandle, who got shipped over to Southern Italy in a B-17 bombardment group and then had a career in corporate life and all the stresses of that—to see it all go away in his body was tremendous. Had we just done the standard funeral thing, his body would have just been picked up and stuffed with embalming fluid, and we never would have seen any of that stuff. We would have missed that one opportunity to heal ourselves from what we felt from him over our lifetimes.

“People don’t know that they can do that. And people don’t know that what they’re missing is that deep connection with their family member and themselves on the transition to death, and how beautiful and deep it is.”

This story originally appeared in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline “Bury Me in the Backyard.” Write to holland@dmagazine.com.