Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

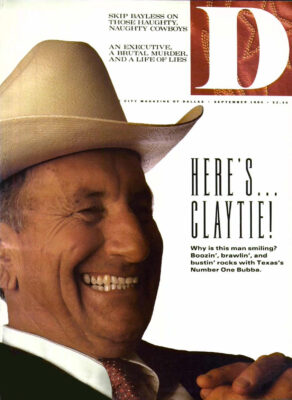

Claytie: The Video: The film is not as explicit as many you can rent today, but it provides graphic proof of one thing: Clayton Williams knows how to have a good time.

This funny home video was shot about five years ago at a black-tie cattle auction in Midland. (This does not mean that the cattle were wearing black ties, so it’s not to be confused with the time Claytie auctioned off the heifers wearing $3,000 strings of pearls. That’s another story.)

Lavish displays of material wealth have never been labeled a sin in West Texas, and this occasion is no different. The ladies of upper-crust Midland are flaunting their rocks and furs the way Mussolini flaunted his tanks. As for Claytie himself, he’s definitely three sheets to the wind. Let’s listen.

Claytie clutches the microphone, his voice drowning out the auctioneer. He’s cutting a private deal with a bidder. If this guy will offer $43,500 for a black cow, Clayton Williams will sing “The Eyes of Texas.” As any native Texan realizes, a true-maroon Aggie would rather be caught reading Wordsworth than singing the official song of that Other School down in Austin.

But what’s this? The good ol’ boy puts down his money and Clayton Williams, literally glittering in a purple sequined dinner jacket, takes the microphone and bursts into song. “The eyes of Texas … uh … the eyes of Texas are upon you … uh … I’ve been workin’ on the railroad … somebody help me with the words … till Gabe-rul blows his h-o-r-n-n!”

Later in the evening, after the booze has kicked the celebrants into another dimension, and grown men are stumbling over match-sticks like they were logs, the crowd of wealthy Midlanders hears more of the music of Clayton Williams. Now he’s singing with a country and western band called Shade Country. Strumming on an electric guitar, Williams bellows out a 20-minute aria, the words of which are as murky as they are at those operas that the big boys of Midland attend, at gunpoint, with their culture-starved wives.

Certain terms, like “Aggie, rodeo, and big buckaroo,” can be understood, but that’s about it. Finally, Clayton Williams finishes his song. An admirer throws his arm around the virtuoso and says, “Damn, Claytie, that was great.”

Williams, drink in hand, turns to the Shade Country band and shouts, “Boys, get it goin’-quick. These people are so goddamn drunk they think I’m great.”

Claytie: The Coronation: Five years later, those who fear and loathe Clayton Williams must wonder if the voters are as drunk as the Midland fat cats on the night of that auction.

At the biennial tribal ritual known as the Texas State Republican Convention, an emotional, grandiose exhibition of red, white, and blue held in late June at the Tarrant County Convention Center, Republicans believe a changing of the guard is at hand. After a century of Democratic domination, the convention would be the ceremonial kickoff of the campaign that could once and for all time mark Texas as a Republican state. And the person to officially apply the brand to the Lone Star backside would be Cowboy Clayton Williams.

By the time he arrives backstage, Texas Republican heavyweights are poised to welcome their candidate. George W. Bush, son of the nation’s chief Republican, stands there in headphones, listening to the Rangers game and grimacing at developments at Fenway Park. “I really don’t know him,” Bush remarks, “but I met him several times at charity fundraisers when I was in the oil business in Midland. The question on my mind is how has he dealt personally with the adverse stuff that happened during the three weeks after the primary. Has all that changed him?” Bush asks. “Has this changed his zest for politics? That’s what I’m interested to find out.”

Is he the future or the past? A friend once told Clayton Williams that he couldn’t ride a horse into the 21st century. “You can if it’s the right horse!” Williams said.

When Claytie marches into the arena from a side entrance, striding through the cheering delegates and waving his white hat, all doubts are erased. What has been an angry convention, splintered by debate over abortion, becomes a coronation-in-waiting. If Claytie lost any of his zest for politics over the rape-and-weather gaffe, his spirit seems renewed now, as he officially declares war on Texas Democrats.

A graph appears on a video screen mounted behind the podium, illustrating the ominous growth of the state budget. The little bar on the left shows that Texas, as a government entity, was getting by on $4 billion in 1968. That number expanded to more than $47 billion by 1990. “Even with my Aggie math. I can see over a thousand percent increase in state spending, and I don’t know about you, but I haven’t seen a thousand percent increase in state services!” thunders the man in the big hat.

The numbers on that graph, Williams insists, represent a modest advance on a kid’s allowance compared to what will happen if Ann Richards and “the Austin crowd” are given control of the credit cards. The same thing applies to the Democrats’ approach to Texas’s public education woes, an approach Claytie likens to “putting a Band-Aid on top of a Band-Aid on top of a Band-Aid.”

Most of the speech is delivered in staccato 12- and 15-word sentences, the kind of plain talk that supporters would expect from the favorite son of Pecos County.

Specifics are few. Williams’ idea of school reform, basically, is to stress “the Three Ds … don’t do drugs,” a departure from what he sees as the approach of an Ann Richards, who, after all, is simply a card-carrying professional politician.

Flag burning comes up. Williams asserts that it took Ann Richards three days to determine her stance on the issue. “It took me about three seconds.”

Then, delegates are treated to an oral outline of what they might expect from life in Clayton Williams’ Brave New Texas. It will be, of course, a drug-free Texas, a Texas where deserving kids can anticipate a two-year shot at college at state expense. (“They’ll have to work nights, but hard work never hurt anybody.”) Finally, Texas, our Texas, will be a place where “somebody’s 13-year-old daughter cannot obtain an abortion without her parents’ knowledge.”

This is Williams’ only reference to the abortion question, and it comes late in the speech. But it serves to bring the Right-to-Lifers roaring from their seats (this one brief utterance from the nominee being the single motivation for their being seated in that auditorium in the first place).

While none of Claytie’s material rings exactly with the echoes of Lincoln-Douglas debates, it is profound enough to draw cheers and happy ovations from the throng at the Tarrant County Convention Center. And if it’s not precisely the stuff of 1990s Republicanism, so be it. Claytie has an answer to critics of his self-styled O.K. Corral political image. A friend, Williams says, “once told me, ’Claytie, you can’t ride a horse into the 21st century.’ And I said, ’You can if you’ve got a good horse.’”

A speech that was originally scheduled to last 12 minutes finally finishes 35 minutes later, closing with Williams tearfully embracing his wife Modesta, while the crowd —several thousand of whom are wearing red heart-shaped “A Lady For Claytie” buttons — roars.

Were it not for the phenomenon of Clayton Williams, the political currents in Texas might be flowing anywhere but toward the Republicans. For one thing, Williams is asking voters to send him to Austin at a time when the Republican incumbent, Bill Clements, owns the lowest approval rating of any governor in Texas history, including Mark White in the days when he was perceived as sinning against the religion of high school football. Ann Richards, on the other hand, seems to have successfully mobilized women as an organized and determined voting bloc for the first time in southern political history. Claytie’s gaffes about rape and getting “serviced” have lost him the support of even some die-hard female Republican activists. And despite what Republicans are saying about crime and drugs being the keys to voters’ hearts this year, the abortion issue is the ballot-box bombshell. Polls are showing that a majority of the electorate is sympathetic to Richards’ pro-choice stance.

So if the Democrats ever had a golden opportunity to retrieve the Governor’s Mansion from a Republican grip, 1990 would seem to be the time.

But in late summer, public and private polls continued to show Clayton Williams leading by 8 to 10 points. Campaign finance filings in mid-July showed Williams raising money at a rate of $3 to Richards’s $1. Those who say that Democrats can lie back and enjoy Ann Richards’ journey to the Governor’s Mansion may not indeed have met Clayton Williams.

ROOTS, PART ONE: LA RAZA FOR CLAYTIE?

Even in West Texas, with its 10,000-square-mile blocks of solitude, Fort Stockton is a unique kind of place. Along Interstate 10, between Kerrville and El Paso, Fort Stockton is a rare stopover where the traveler has an option of more than one restaurant. That is a 390-mile stretch.

Around these parts, absolutely no one who grew up with or around Clayton Williams was surprised by his resounding win, over several better-known rivals, in the Republican primary. Nor were they particularly surprised when Williams informed a gathering of major media reporters at Williams’ Alpine, Texas, ranch — folks primed to quote cactus plants and moo cows, if necessary — that “bad weather is like rape; if it is inevitable, just relax and enjoy it.”

Not that the townspeople were all that thrilled about Williams’ little fireside chat.

“That’s just Clayton,” sighs a middle-aged waitress at Sarah’s Cafe, a landmark establishment in Fort Stockton that could become the West Texas equivalent of that feed store where the Carter brothers used to hangout. “Around here, we just refer to it as that silly remark Clayton made about the weather.”

The home boys were less forgiving of Blunder II in Williams’ post-primary malaise, when Claytie admitted that he frequented cat houses as a young man and implied that “getting serviced,” as he expressed it, was as normal a part of growing up in West Texas as getting baptized.

“Well, he was right about one thing. A lot of kids did that,” says Gregg McKenzie, a Pecos County commissioner. “Although I’m not going to say that I did.”

Ever since he was just a li’l buckaroo, Claytie Williams has been comfortable with horses and guns. Sometimes, however, the Indians—and his own words—come back to ambush him.

But gaffes or no, McKenzie and other Williams cronies believe that the man has enough of the right stuff to win in November. For one thing, Williams has the strongest ties to Hispanics of any modern Texas Republican. Traditionally, and especially in recent times, the Democrats pin their hopes for victory on landslides in the mostly Hispanic boxes from the Rio Grande Valley. Williams, who delivered six or seven minutes of his Fort Worth speech in a slow, drawling Spanish, may cut into the Hispanic vote. He’ll get nowhere near a majority, but if he could crack the Democrats’ Hispanic lock with even 10 or 15 percent, it could be a lethal blow to Ann Richards, especially if Williams is able to good ol’ boy his way into similar gains in yellow-dog Democrat territory, East Texas.

McKenzie recalls that at the end of World War II, the city of Fort Stockton integrated, a bold stride in regional race relations, “That’s with the Mexicans, that is,” the commissioner says, speaking the standard Fort Stockton drawl. “Until then, they weren’t allowed to go to school. They had to sit in the balcony at the movie theater and weren’t allowed in the public swimming hole, which was part of Comanche Springs. The Mexicans had to go down and swim in the creek.

“There was a little trouble, at first, with integration and all,” McKenzie recalls. “But I remember Claytie having a lot of respect for the Mexicans. He could speak Spanish fluently in high school. And even to this day, if Claytie is in a room with a lawyer and a banker and some old Mexican cowboy walks in, Claytie will ignore the other guys and go over and hug the Mexican’s neck.”

After a stint at Texas A&M and later in the U.S. Army, Williams returned to his Fort Stockton roots. He sold insurance and dreamed dreams of ways to scratch his itch to get rich. Claytie was clearly a disciple of what was then the unwritten law of Texas finance: scrape up every dime that you can (about two grand, in Williams’s case, money he says came from selling insurance and waiting tables in Mineral Wells) and roll the dice in the oil patch.

“I remember Claytie sitting down in a restaurant one night years and years ago and mapping out exactly what he was going to do with his life,” says Fort Stockton optometrist Omer Price. “He said he would make a million dollars, go on an African safari and kill a lion, and marry a beautiful woman. It doesn’t take a special man to say those kinds of things, but Claytie’s the only one I know who then went out and did it.”

Clayton Williams’ zodiac was apparently in order when the time came for him to make a stab at his special destiny. His first well didn’t come in until 1959, but after that, the drilling successes appeared in such sufficient numbers that Williams would found (in 1961) Clajon, a company that would become the largest individually owned gas company in the world. The next venture would be investment in raw West Texas land, which would lead to cattle raising. This is Claytie’s strongest area of business endeavor, since he was trained in animal sciences at A&M and maintains a passion for techniques in insemination and advanced embryonic transplant. His ranch near Alpine, adorned with a large boot-shaped swimming pool, is the seventh-largest venture of that type in the country.

By now, Williams had moved up the interstate to Midland, that unusual tract that at one time probably contained the largest assortment of rural millionaires in the United States. It was there that he met his wife Modesta in a Mexican restaurant in the mid-’60s. “I’d go in there and drink beer and sing with a mariachi band. Modesta was in there with a girlfriend. I like to say that we sort of picked each other up.”

Williams was living in “Middling” on New Year’s Eve 1975, when one of his wells came in with such force that a small town had to be evacuated. That hole in the ground in Loving County began producing $50,000 worth of natural gas a day. Claytie would establish a bank and Claydesta Communications, which is heavy into digital and fiberoptic communications — a fact that Williams is quick to point out when political foes accuse him of maintaining a stagecoach mentality at a time when Texas requires some progressive ideas.

In the process of creating this flatland business duchy, Claytie may have stepped on some toes along the way and established a few enemies here and there. But even his detractors will concede that few Texas fortunes were ever established on the basis of fair play and altruism.

Williams’ success came just in time to stage a tough and largely successful battle to stay on top in the midst of brutal economic calamities that would wrack West Texas. At the dawning of the ’80s, Williams was fond of joking to friends that “I’m in oil and gas, real estate, banking, and cattle — everything that’s losing money.”

By the mid-’80s, as oil hit rock bottom, Claytie found himself in the unenviable position of having “seven banks breathing down my neck.” He was forced to sell off Clajon to satisfy his creditors, and everyone still employed by the crumbling Claydesta empire took heavy pay cuts. “It was a very difficult time for me and my family,” Williams says. “We had bankers literally on our doorstep ready to shut our business down. We had to retrench, consolidate, sell. But we survived.”

Even people who have known Claytie for half a lifetime were a little gap-jawed when the man actually pulled the trigger on what seemed a wild and wicked dream to become governor of Texas. Risking everything you own on a 20,000-foot oil well is a calculated risk. Tossing millions into a scheme to become governor, many of Clayton Williams’s friends were convinced, was simply a daredevil stunt.

Obviously it’s a stunt that appears less zany with time. A year ago, marketing surveys indicated that Williams commanded exactly 4 percent of the vote; six months later, Williams would write what campaign organizers from throughout the land regard as a significant chapter in modern American political history. Nothing is unusual about some well-heeled wheel horse from the private sector poking his head into the political prize ring. But the amateur usually gets his head handed back to him. Claytie may be a different story.

“When Claytie actually announced for the race, I thought he was crazy,” says Ted Collins, a Midland oil executive who is one of the few who can paddle his canoe on the same pond as Williams. “Nobody east of the Brazos had ever heard of him. Now, to say he’s crazy is not to say I was surprised that he ran. Everybody who knows Claytie knows he’s on a hard-core ego trip. But he’s got the guts of a daylight bank robber.

“A couple of years ago, everybody out here was speculating that he might be about to go broke. Now look at him. The guy is stronger than horseradish. And that TV ad personality is no act. He’ll drink beer and dance on the table and sing Mexican songs all night, every night.”

Does pure bravado entitle a person to govern the third-most populous state in America? Voters, so far at least, apparently deem it a strong qualification. Certainly, no political unknown before Clayton Williams has proceeded so far on the wings of a five-word phrase: “the joys of bustin’ rocks.”

ROCK ON, CLAYTIE

Williams seems to have struck pay dirt with his idea of hard labor boot camps for adults and teenage drug offenders. It sounds tough — and it sounds cheap. “They have one already in Georgia, and I visited it,” he says. “I thought that breaking up rocks in the Big Bend, to be used for roads and picnic tables, would be useful. The camp would be arranged around a 90-day boot camp, followed by a six-month work camp. The kids would get paid for that part of it. If they complete the boot camp and the work camp, the drug conviction goes out the window. That’s a lot healthier situation than prison. Once a kid goes to prison, you lose ’em forever.”

The problems of his adopted son, Clayton Wade Williams, inspired his efforts to fight drugs, or at least make that the focal point of his campaign. “Early on, Clayton had some problems with his self-image because he is adopted,” Williams says. “Sometimes that happens with kids; sometimes it doesn’t. We have another adopted son, and he never had any problems like that.

“Young Clayton had problems with beer and marijuana. He never reached the point of cocaine or the stronger stuff. But he got kicked out of high school, and Modesta and I enrolled him in the S-T-R-AG-H-T program in Richardson.

“Then he spent a year at Sul Ross (State University], but he didn’t do well in his classwork and started drinking beer. That might sound harmless. But he’d go off drinking beer with fellas and the next thing you know, somebody’s passing him a joint.

“Before I decided to run,” Williams says, “the whole family talked about how the campaign would affect us all, but particularly young Clayton, and how his problems would become kind of a public thing. He said, ’Go for it, Dad.'”

Joe Milam, partner in a 10-person Midland ad agency called Admarc, got the idea for the now-famous bustin’ rocks commercial that sent Claytie’s campaign into the stratosphere. Milam had produced a spot for Claydesta Communications in 1985 that featured Williams as a company spokesperson. The theme was a Pony Express station, and Williams was dressed in “period Western attire.” The company CEO seemed so natural, and so effective in front of the camera, that Milam was eager to tap that hidden talent again. He recruited the college rodeo club from Sul Ross State University in Alpine to play the roles of doper/rock-bust-ers and dressed them in tightly pressed convict costumes (actually, they were used security guard uniforms, purchased for $6 a piece). While the cameras rolled, the students pranced in a tight formation up and down a rocky hillside, swinging shovels and pickaxes while Clayton Williams, grinning in the foreground, outlined his plans for the sniggly little dopers responsible for Texas’ ’90-style crime-gripped paranoia. For their efforts, the actor/rock-busters from Sul Ross were paid $50 a day and all they could eat and drink.

The Admarc commercial has become a landmark in the annals of electronic image-making. People within that industry assume that Admarc people came up with the bustin’ rocks slogan, but Joe Milam will tell you that the inspiration for that was pure Claytie. The candidate himself might have been inspired by an Alabama political race about 15 years ago, where a law ’n’ order candidate successfully campaigned for the office of attorney general with the battle cry. “I want to fry ’em until their eyeballs pop out and green smoke comes out their ears.”

Clayton Williams figured that bustin’ rocks was more suitable for the general tastes of chic Texans, a perception that enabled him to blow the doors off the combined Kent Hance-Jack Rains-Tom Luce Republican establishment.

Instantly, the former student body king of Fort Stockton High became an international celebrity. “Mr. Clayton Williams’s television commercials were of a quality that would have met the standards of the most demanding automobile manufacturer,” wrote the Economist magazine, the British version of Fortune.

“And once he appeared on televised debates with the other candidates,” the Economist continued, “Mr. Williams demonstrated an ignorance of government that would have done Mr. Ronald Reagan proud.”

Primary election results proved that voters do not place much value on a candidate’s grasp of constitutional government. This seemed particularly true in Midland-Odessa country, where Texas crude is the hemoglobin for an entire society. One would have thought that Clayton Williams was the man who rescued little Jessica McClure from the bottom of that well shaft in Midland. He carried 76 percent of the vote in Ector County.

If Williams wins, his victory will mean several firsts for followers of Texas political trivia. First Aggie to be elected governor. First person who publicly stated that he was an eager patron of whorehouses to be elected governor. First person who is a second cousin of “Mad” Eddie Chiles to be elected governor.

“How can you not vote for Clayton in November, against a woman who couldn’t balance her own checkbook?” asks Midland oilman Ted Collins. “I don’t believe there is any way he is going to not win.” he says, adding the caveat that keeps Republican campaign organizers on edge, “as long as he keeps his big Aggie mouth shut.”

Clearly, following his tenure at Texas A&M, Williams was involved in extensive graduate studies at the Jerry Jones Academy of Tact and Elocution. But is there an old Aggie anywhere in Texas who would not vote for Clayton Williams in the general election?

ROOTS, PART TWO: WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE?

There is a lot of unwritten history about Clayton Williams’ birthplace, Fort Stockton. Persons of the Comanche and Apache persuasion used to fight over it in the 1800s, committing unspeakable atrocities upon each other for the property rights. Much blood was shed over a bubbling spring that gushed from a benevolent outcropping of the Edwards Aquifer. As was always the case in disputes of those times, the Comanches prevailed, and the area became a significant location on their war trail into Mexico.

Ambitious white folk, when they first began sniffing around that magic spring, encountered an awful reception at the hands of the Comanche. According to the tribal penal code, trespassing was an ant-bed offense.

The post-Civil War United States Cavalry would ultimately provide some muscle on behalf of the buckskin-clad venture capitalists. Thus the name Fort Stockton. Officers’ quarters and what was apparently a mess hall from the original government encampment have been restored as a shrine to the Anglo land grab and are currently available for inspection.

With the Great White Father acting as an around-the-clock security guard, irrigation systems adequate for about 150 farms were established around the creeks and streams that emerged from the mouth of Comanche Springs. They grew alfalfa that was baled into cattle feed and shipped via railroad throughout the West. Even melon orchards became prosperous ventures.

But into this idyllic scene came a stock figure of the Western plot: the greedy land baron.

In 1952, a landowner north of Fort Stockton tapped into the aquifer and, with diesel-powered pumps, flooded his farm land with 70 million precious gallons of water each day — at least 50 million gallons a day more than the spring was producing. That land baron was Clayton Williams Sr.

A group that called itself Pecos County Water District No. 1 filed suits against Williams and a few other pump farmers, and after a two-year legal wrangle the dispute found its way to the Texas Supreme Court. Those jurists ruled that the water Williams Sr. was using on his pecan grove was “a well-defined surface stream” that happened to be running beneath the ground, and that ground water in any form belonged to the landowner.

So Claytie’s father kept on pumping through the longest West Texas drought since the darkest days of the Dust Bowl. By 1962, Comanche Springs and its fertile accompanying landscape were nothing more than happy memories. An eight-year drought of another variety, this one on the worldwide commodities market, presented West Texas with additional devastation. But as far as Fort Stockton was concerned, the music died when the well went dry.

Leap forward to 1986, when an event some determined to be an act of God took place in Fort Stockton: after back-to-back years of unusually heavy rainfall, and the suspension of pumping operations by Belding Farms, a farming conglomerate, Comanche Springs began to gurgle and spit again — not with its old vigor, but to the tune of 2 or 3 million gallons a day. The community of about 10,000 rejoiced.

Citizens, some with long memories, approached the Fort Stockton City Council, hoping that a new water district might be formed to protect the revitalized spring. But there was opposition. Clayton Williams Sr. had passed away in 1983, but Clayton Jr. was there to take his place.

“He fought us tooth and nail,” says writer and publisher Kirby Warnock, who lives in Dallas but still owns the Fort Stockton farm that was established by his grandfather in the ’20s. “Clayton himself only appeared at some of the meetings, but his Fort Stockton lawyer, Paul Dionne. was there at all of them, constantly raising points of order and keeping anything from getting done.”

Finally, the Fort Stockton council decided to table the water district proposal. Williams continued pumping, and now the spring is dry again. “I’m not going to say that Williams has that council in his back pocket,” says Warnock, “but he is a person of considerable influence out there. He’s selfish and mean-spirited and completely oblivious to the art of compromise. It’s either his way or no way.”

Williams’ people insist that his family is not responsible for the problem, but a 1962 Texas Water Commission report concluded that the wells on Williams’ land depleted the spring.

It’s pretty clear that sour notes like Warnock’s are not plentiful in Claytieland these days. Not everyone experiences the acrid aftertaste. “My grandfather [D.V. Rowels] saw his beautiful alfalfa farm ruined when the spring dried up,” remembers Doris French, now of Fairfax, Virginia. “Waving green fields reduced to wasteland. But my 91-year-old grandmother [Mrs. D.T. Germane, now living in McAllen] is strongly behind Clayton Jr.’s campaign. And she is not a very forgiving person.”

So how is it that a person whose family is blamed, by some, for turning what was once a rare oasis into a moonscape, can be so universally popular in Fort Stockton?

“The people who would have most reason to oppose him were all forced to move when the spring dried up.” says Kirby Warnock, whose grandfather lost a profitable alfalfa business as a result of the elder Williams’ action. “Now they think Fort Stockton will have its own personal representative in the Governor’s Mansion, and that all sorts of pork barrel benefits will be headed out that way. So even the people who might not like him have pretty well shut up.”

THE BRAINS BEHIND CLAYTIE

For the past 21 years, Dick Leggitt’s job has been to transform mortals into gods, or at least create that illusion for the voting public. Maxey Jarman, who owned a huge company that manufactured shoes and therefore felt he should become governor of Tennessee, hired Leggitt away to become his press secretary during the campaign. When the votes were finally counted, the shoeman got the boot. “That was my first lesson with politics. Being rich ain’t enough,” Leggitt says.

Despite the setback, Leggitt found something terribly seductive about the sights, sounds, and aromas of backstage politics, although he will concede that the smell is not all that pleasing at times.

“Every time I involve myself in a major campaign, I swear it will be the last,” continues Leggitt, 48, a vice president with Robert Goodman Agency out of Baltimore and Dallas. His company is one of the big five in the field of political consultants, which handle 60 percent of the major campaigns in the United States. One of the others, Squier-Eskew Communications, is orchestrating the Ann Richards parade.

Williams declared “no more mud,” then slammed Richards for taking contributions from a group supported by Jane Fonda.

For the Clayton Williams handlers, of whom Leggitt is the most prominent, the post-primary lull has produced some tense moments. The opinion polls, which appear every other week, are breathlessly monitored. Williams’ summertime margin appeared safe, but not insurmountable. “This stuff is a lot like football,” says Leggitt. “Our team is ahead going into the second half, so the object now is not to fumble or make mistakes that give the other team, you know, momentum.”

The primary, as everyone knows, produced an unmitigated triumph for Williams and the vote-gathering brain trust that surrounded him. Organizers from other states call the Williams operation one of the slickest in the history of modern political marketing. The set-up operated around Leggitt and his people in Dallas, the Admarc people in Midland, and Dresner, Townsend, and Sykes out of New York.

“So far, it’s been harmonious,” says Leggitt, who admits that there was one flare-up. The original bustin’ rocks spot was produced with a strange background sound track “like choir music” that he didn’t like. After some hard rethinking, it was agreed by all that the choir had to go.

After the post-primary euphoria wore off, it was inevitable that the summertime tension would creep in. Williams himself generated the angst with what Leggitt calls the “rape-service thing. But we did extensive surveys that determined that only 6 percent were turned off by the remarks.”

It wasn’t until midsummer that the Williams team studied the latest polls and located a downtick. “This was after the school funding mess and a lot of people were not happy with [Governor Bill] Clements, who came out of the thing looking like a mean old man who doesn’t give a damn about Texas school kids,” says Leggitt.

It became a priority of Claytie forces, then, to distance their man as far as they could from any identification with the incumbent and those plaid sport coats of his that are more commonly sported around the crap tables in Atlantic City.

At this stage of the race, strategists attempt to “wear the other hat” — that is, become the devil’s advocate and anticipate where and how the hated foe will strike when the campaign for the big prize heats up in earnest. Dick Leggitt, who wears the other hat for the Williams camp, imagines that the Ann Richards folks are pondering conspiracies against Claytie of Shakespearean dimension.

In a remarkably futile gesture, Williams asked Richards to “Read my lips… no more mud,” but he later attacked Richards for accepting campaign contributions from the Hollywood Women’s Political Committee, a group supported by Jane Fonda, reminding voters of the actress’ anti-Vietnam War protests more than 20 years ago. “I think that’s an issue,” Clayton Williams says. “That’s not mud-slinging. Armed forces veterans look at this business as something offensive. I’m a veteran; Ann Richards is not.”

Whether acting in cahoots with the Richards camp or not, producers from ABC’s Prime Time Live snooped around the state for several months, seeking dirt on Clayton Williams and his allegedly risque behavior. They have returned to New York seemingly disappointed in what they were able to unearth. However, since ABC spent more than $100,000 in its effort, Williams’s handlers are certain that a piece will appear sometime in the fall. They can only presume that the “Eastern liberal establishment” will not provide a favorable perspective of their client.

And Williams has now been linked, in mailers sent out by Democratic national chairman Ron Brown, to ex-Klansman David Duke of Louisiana and conservative troglodyte Jesse Helms of North Carolina. Brown seemed to imply that Williams had KKK loyalties. “That’s bothered me,” Williams says. “It really has. I don’t have a racist bone in my body. The rape thing … I made that remark to a couple of cowboys. I didn’t know that reporters overheard it. But it was still stupid, and I sure regret it. Hopefully, these experiences might help make me a better governor. I think we’ll win, but we’ve got a long way to go.”

It’ll be a long, muddy path, and it is the abortion issue that promises to be the most nettlesome in the final stretch. Williams remembers well the Life vs. Choice squall that blew chilling winds through the Republican convention in Fort Worth. And he’s not about to become sucked into the center of it. “We’re hoping that our lead [in the polls] will be so substantial that NARL [the National Abortion Rights League] won’t spend money on Ann’s campaign,” Leggitt says. “I saw what they did in Virginia. They ran these spots with some actor dressed up like a doctor — sort of a Marcus Welby character — talking about how teenage girls would be going the coat-hanger route if the Right-to-Life candidate got elected. And the Right-to-Life guy — who had a 12-point lead with six weeks to go — got killed.”

Leggitt remains hopeful that the good folk of “Tahoka and Sweetwater and the grassroots Texans” won’t allow that to happen to their Claytie. He lets it be known that while he works in a company of button-down ad men on the Eastern shore, he can never shake his roots in Hereford, Texas, deep in the heart of Claytie Country.

“The guy is genuine,” says Dick Leggitt. He insists that Clayton Williams is not some drugstore, Hollywood cowboy who, after the day’s filming is complete, rides off into the sunset with his hairdresser.

“I guess that, to me, Claytie represents a time and place that a lot of Texans who are old remember and long for,” Leggitt says.

“A more open and cordial society.”

Huh?

Author