Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

Sticky rivulets of Weller, gin, and Jack Daniels washed down my lower arms and then to the floor through my fingers. The cocktail napkins scattered on my serving tray dissolved into white splotches of wood pulp. They looked frothy, like mini-icebergs stranded on a carbonated sea of spilt whiskey and Coke. Embarrassment and self-pity engulfed me as I was batted about by drunken members of the crowd. I wasn’t used to this. I wanted to roll up in an old horse blanket and die somewhere. Somewhere dry. Even the floor felt swampy, ready to gobble up my wobbly ankles and feet.

My only hope was to reach the waitress station — a dimly lit alcove the size of a utility room — before the smoke and sound smothered me completely. I made a determined dash, wiggling under elbows and over many different sets of legs, gaining incentive by mentally measuring the diminishing distance. At 25 yards, I could see the silhouettes of the other waitresses. At 30 feet, the girls began to wave. Finally, I jogged up three steps, almost tripped from my own recklessness, then realized I was safe. And there.

The biggest honky-tonk in the world was packed. There were 8,243 undulating torsos (that’s 1,743 beyond what the fire marshal has declared to be legal capacity), crammed rafter to rafter, wreaking havoc, celebrating mayhem, all standing on their chairs to get a better view of ZZ Top.

The band was throbbing its earthshakingly amplified tribute to man’s primal motives:

I’ve got a gal; she lives on the hill. She won’t do it, but her sister will…

Seven of us, all waitresses, huddled hip to hip. The situation was clearly getting out of hand. One of the girls shouted: “Don says not to go into the center of the crowd. Do not go into the center.”

She do the boogie-woogie, baby. Boogie-woogie all night long…

“What?” said one of the others. Through the smoke of the cigarette she was holding, I could see bits of sweat beading on her nose and brow. We were all tense. We had to shout to be even faintly audible to each other.

“Don says not to go into the center of the crowd. A waitress has been knocked over and hurt.”

“Who? Who?”

“What?”

“I don’t know. Just fell down or got pushed. Don sent her home. I think it was one of those two from Albuquerque. She hit her head.”

“Oh, my God.”

“So what’re we s’pposed to do?”

“Don says serve people up and down the aisles. Up in here, see. But don’t go into the mob, okay? It’s not worth it. There’s lots of money to be made up these aisles.”

I chucked the soggy cocktail napkins into the trash, placed my cork-lined tray on an empty beer case and turned to Tammy, one of the 12 new waitresses — 13 including me. Tammy rolled her eyes and gave me a contemplative look I couldn’t interpret. The corners of her mouth were tight. Then with the fastidious and slightly apprehensive mannerisms of a domesticated raccoon, she took all the money out of her cash caddy and quickly crammed it into the front pockets of her jeans.

The trash bin was leaking again, and the floor of the waitress station was like a reflecting pond with wildly varied highlights glistening on a thin pool of stinky beer. I waded over to Tammy.

“Making anything?” This, I had learned, is the way cocktail waitresses initiate conversations.

“Eeeeeeh. Not really,” she said. Then, in a whisper: “Screw this. Let’s get outta here, listen to the band. We can see the show!”

I’d been surprised when Tammy told me she was 19. She seemed older. I liked her, admired her really, for being able to quit for the night and call everything off so effortlessly. I followed suit.

I felt as though we’d slipped out of school. The crowd was going crazy now, and there we were — unsupervised! People loomed out of proportion from the height of their chairs. The shadowy figures swayed like dandelion stems, their faces aglow from the golden stage lights. Everywhere the air was white and rank, heavy with the smoke of several thousand cigarettes. Tammy and I trudged on, our heads at the level of their hips, until we found some people willing to spare a chair. I found myself standing next to a raggedy-toothed young man drinking bourbon from the bottle. Behind us, people were passing a reefer rolled as thickly as a Cuban cigar.

I could just barely see the tops of the heads of the men on stage. The guy next to me yelled “Lift you up?”

“What?”

“Want me to lift you up?”

“No, no.”

Then I fell into a trance. It was the first time I’d felt my real personality coming back to comfort me. I’d been so caught up in the spilt drinks that I’d forgotten to remember that this place, for me, was only temporary. I was not really one of these people. I told myself: “Don’t worry. This will be over soon. You’ll get out!”

Then I realized that the people in the audience, the people with whom I’d just resumed my rightful place, also saw Billy Bob’s as temporary. Even the waitresses come and go; they stay until they realize that life’s too short. It’s temporary.

What’s permanent are the people ready to fill the places left by those who disappear. It’s not even the people or the place that will endure then, it’s the predicament: cocktail waitressing, an indentured bondage. Servitude for spare change. It’s based on the concept that if you smile and act humble before faceless strangers when you bring them their drinks, they’ll leave extra money on your tray.

It is a job many women find degrading. It is not a job for which our culture reserves a great amount of social esteem; nor is the title “waitress” one that many women would want etched on their tombstones. But when I report for work each night at Billy Bob’s Texas, I have to deal with another term. Imposter. Perhaps even “fraud.” I was, as they say in B movies, not really a waitress. I am a journalist; perhaps a voyeur as well. I was out to see life on the other side of town, to experience a foreign world, and then return to my safe, secure, white-collar world to write about it.

Thinking this, holding on to these racing thoughts, afraid I might lose them all if I didn’t tie them down, I turned to Tammy. She was clapping her hands, swinging her hips from side to side, periodically throwing her dark hair over one shoulder. Her eyes brightened, and she shouted something I couldn’t hear over the music. I leaned close enough to feel her breath in my ear.

“They’re great!” was all she was saying.

I hadn’t been listening.

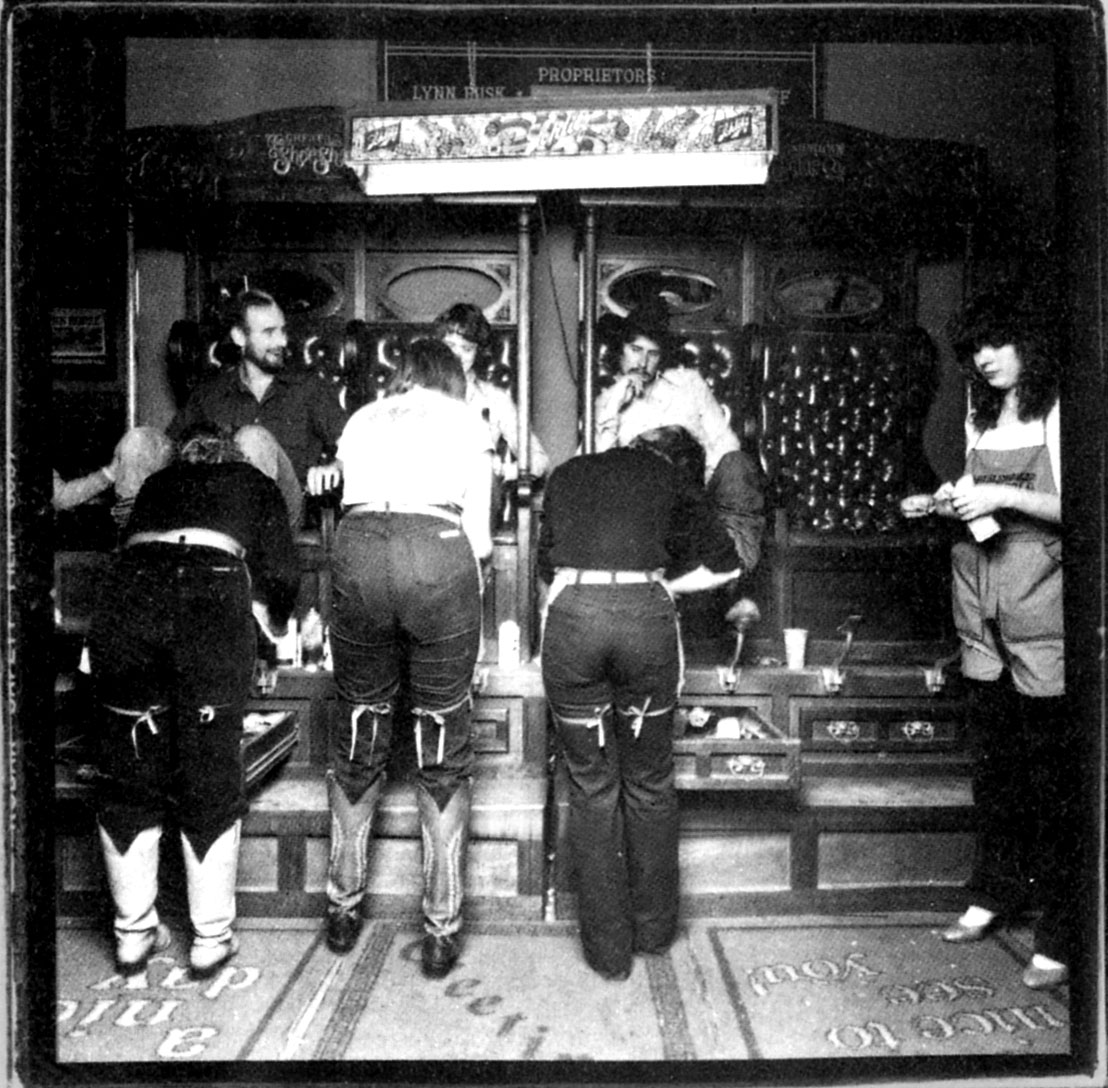

From Fort Worth’s Main Street, Billy Bob’s Texas has the institutional look of a museum or a monument on the scale of something you might see in Washington, D.C. This is not to say it is an attractive place from the inside or the out. It’s not. There is a falseness to the painted adobe-toned concrete and a Disneyland look to the building’s restored exterior. There isn’t any greenery or landscaping to speak of around the 127,000-square-foot structure. A garish Billy Bob’s Texas marquee looms above the four-lane street telling passers-by in no unsubtle terms about the live entertainment of the week. Flags of Texas are staggered across the honky-tonk’s roof, and special speakers transmit country music into the lot to pacify the people waiting for tickets. Sometimes management forgets to turn the speakers off, and the music murmurs on all night spewing melancholia.

The building once housed a Cook’s Discount Store. Before that it was used during the Fort Worth Fat Stock Show. The stockyards lie just behind the club, close enough to enfold the building in a cloud of pig and steer smells when the wind is right. During the day, the enormous front lot is spotted with the old trucks and cars of a few employees, but at dusk the place takes on a pulsating vitality. It becomes a rumbling, puffing, and blinking throb as if the surrounding property were one trembling engine, one big machine.

Mickey Gilley ain’t got nothing over Fort Worth now that Billy Bob’s Texas is the biggest, baddest honky-tonk in the world.

When Billy Bob Barnett, a well-moneyed Lampasas native, and his entourage of interested investors decided to build a nightclub that would outdo Mickey Gilley’s famous establishment in Houston, they relied most upon the know-how and venture capital of Fort Worth nightclub magnate Spencer Taylor. What they built was the ultimate in Texas overstatement.

40 bar stations. Count ’em. 40. A 30,000-square-foot dance floor. A 48-by-22-foot stage for live acts. A real rodeo ring with bleacher seats for 500. No mechanical bulls; real bulls. A private club for VIPs. A dry-goods souvenir store. Twenty-three pool tables. Pretty girls giving sexy shoeshines. An oyster bar and a pizza place. Video games. Portrait studios. Popcorn stands. No one has ever seen anything like it. People will flock to it from all parts of the world.

No one’s saying how much either Barnett or Taylor and the other partners have sunk into the bottomless pit of a project. Suffice it to say that few cities outside Texas could support another country and western nightclub in a heavily clubbed part of town more than a year after Urban Cowboy was released, just when country was starting to seem “uncool.” Maybe Billy Bob’s Texas is a testament to the Fort Worth ego or the egos of its native sons. Surely the biggest honky-tonk in the world means more to its owners than the dollars and cents that went into it. But maybe not; maybe it’s just the biggest, brashest nightclub money-making scam to ever hit the Guinness Book of Records. One thing is certain: If disco is out and country and western is well on the wane, people will still be honky-tonking someway, somehow. The people running Billy Bob’s are banking on that.

The club has four “phases,” so it won’t seem empty if only a thousand people come out some night. Phase I is when the front bars and the dry-goods store are the only things running. Phase II is when recorded music is being played and the club is host to up to 2,000 people. Phase III is when a live band is on stage. Phase IV accommodates 6,500 people and is like a candle flaming at both ends: rodeo, jewelry store, restaurants, pinball and video games, even portrait artists to immortalize you in chalk and paper, so you’ll never forget what you looked like at the precise moment you were there.

It’s hard to describe the size and scope of Billy Bob’s Texas in words without resorting to cartoonish expressions like Powwww! and Whammmm! It is a rush just to walk into the place. Whhhhooppp! It swallows you up at once. Big as an airport. So dark and cavernous that you find yourself checking for bats. And music — loud music — blaring from speakers standing as high as houses.

And it’s the illusion of strength, this idea that biggest means best, that attracts dozens of employee applicants every week. The jobs that are perpetually open are for cocktail waitresses. No experience necessary. For your time, you get $2.01 an hour and whatever you can wrangle for yourself in tips.

I remember turning in front of the full-length mirror in my Dallas apartment an hour and 15 minutes before I was due in Fort Worth for what I thought was to be my waitressing interview. Something about the costume was wrong. I was wearing my own jeans, an oxford-cloth shirt bearing the nametag of my brother’s prep school roommate, Frye boots, and a borrowed doeskin jacket that smothered me in fringe. I changed shirts. Still bad. I jogged to the medicine cabinet and found an old tube of Mary Kay eyeliner sealed with a scab of its own contents. I brushed on some mascara, too. Improving some, but still all wrong.

The problem, I decided when I glanced into my car’s rearview mirror and saw the top of my head, was with my hair. The short haircut comes from Neiman’s and is, in my mother’s words, “smart.” I didn’t think smarts were going to be what I’d need.

My looks didn’t matter, as it turned out. My being reared in Chicago didn’t matter, and the mysterious three-year gap in my employment record from 1978 to the present didn’t matter, either. What you do to get a job at Billy Bob’s is wait, however patiently and as long as it takes.

I found Don Howard, the man who hires and fires all waitresses, at the designated hour in the VIP Room, a bar within a bar for people who pay a $300 annual membership fee. The VIP Room is the site of most of Billy Bob’s parties, public and private; it’s the only part of the club except backstage in which you can be somebody or do something to garner attention. If you dance on a table or yodel real loud in Billy Bob’s proper, you’re apt to get ignored; in the VIP Room, you’ll get laughed at. So there Howard was in the VIP Room being cool. A slight man with coarse whiskers, Howard always wore a black hat, jeans, and a Western-cut corduroy sport coat. He surveyed me brusquely from under his hat and asked me to take a seat in the management office, an outer holding cell trimmed in chocolate-colored paint that was chipped in several places where office chairs had hit the walls. I took a chair beside a heavy-set waitressing applicant who introduced herself as Jeannie. For 15 minutes or so, we sat quietly, watching the telephone receptionist punch blinking red buttons and listening to her say “Billy Bob’s Texas… Jerry Max Lane and the Hill City Cowboy Band… $3 for men, $5 per couple… Unescorted ladies get in free…” in a lyrical little country voice, over and over.

It’s hard to describe the size and scope of Billy Bob’s Texas in words without resorting to cartoonish expressions.

Every minute or so, someone would burst through the door on the left-hand side of the small room, step over our feet and into the next corridor. Howard strode through six times, clomping his boots heavily with a gait that was obviously calculated to display superiority. Each time, Jeannie and I sat up straighter and looked as though we were ready to be spoken to. Howard never acknowledged us, but it was clear he knew we were there.

“There he goes again,” Jeannie whispered after Howard had passed us by for the fifth time. “Sure is a lot of coming and going here. Busy!”

A well-tanned, dark-haired man swaggered into the room wearing a classy looking brown suede sport coat. The man stopped at the desk and rifled through some messages, then left the room.

“Wasn’t he a nice looking man!” Jeannie said in a grandmotherly voice with a didn’t-you-think-so curled onto the end.

“That was Spencer Taylor,” the receptionist said as she shifted the mouthpiece beneath her chin. “Whoops, hold on.” Buzzz. Click. “Billy Bob’s Texas.”

Howard suddenly rematerialized. All told, we’d been waiting about 20 minutes. “Read this,” he said, handing me a Xeroxed sheet of paper. “Read this,” he repeated when he handed Jeannie the same thing. “There will be an orientation meeting tomorrow at 3 p.m., and all your questions will be answered then.”

“There’ll be some part-time openings?” Jeannie asked.

“I said all your questions will be answered at that time.” Howard turned to leave.

“Three o’clock,” I said.

He was gone.

“Golly,” Jeannie said as she folded the paper into eighths and jammed it into a pocket. “Now I’ll have to miss some work tomorrow. Don’t you think he could have told us that before making us wait all this time?”

The three o’clock meeting was actually a get-together for working employees and an opportunity for them to meet George Bray, the new director of personnel.

They seemed to like Bray straight off (Jeannie whispered: “Now he’s a nice looking man.”), maybe because he used an appealing country guy/football coach vernacular that made them relax into forgetting he’d just been appointed the nightclub’s Mr. Fixit.

After the meeting, the waitressing applicants (there were six of us now) sat together on the top two rows of bleachers and watched Don Howard talk to some people, then leave without acknowledging us. Where’d he go? He was here a second ago. Do we have jobs?

We found him in the VIP Room. He had another meeting to go to, he said, and he’d be back with us after that.

An hour and a half later, a couple of girls got up to call their husbands to tell them they were running late. We’d exhausted our topics of conversation by then. We’d discussed country music (“I love Willie Nelson,” said one girl. “He looks like a dog but can sing like a dream.”); we’d listened to stories about utility cutoffs (“All my life, we’ve been jacked around, having some utility cutoff or another,” Tammy said.); and we’d exchanged what folklore we’d heard about the club. “If you’ve worked at Billy Bob’s Texas,” one girl said, “you can go off and work in any nightclub in the country.”

“That’s true,” Tammy said. “My parents wanted me to get an office job or something, but I said ’no way, man.’ This is where all the money is.”

“Oh, and watch the floors,” a girl named Connie said.

“That’s right, that’s what I heard,” said Tammy. “A friend of mine who worked here said she found a hundred-dollar bill by the popcorn machine.”

“Can you imagine?” someone said in awe.

Every so often, Jeannie would glance at her watch and say it didn’t seem right to keep us waiting so long.

“I don’t mind,” Tammy said. “I got nuttin’ to do.”

It was well past dark when Don Howard and George Bray came out of the management office. Howard’s hat was pushed up toward the back of his head. Bray’s sport coat was open, and his hands were pocketed in the front of his jeans. Thumbs out.

“Okay now, girls,” Howard said, “You’ve all met George Bray. You’ve filled out applications, right?” We nodded.

“There will be a waitress training session Saturday at one. Okay? So ya’ll need to be there, and then you’ll know whether we can work you in or not.”

“What should we wear?” Tammy asked.

Bray moved a little closer to the table and said, “Come naked.” There was an awkward silence.

“Okay, so thank you all for coming,” Howard said in his best stage voice.

We gathered up our purses and coats.

“And we’ll see you Saturday.”

Outside in the cold, Jeannie pulled the furry hood of her parka up over her head. “You’d think they could have told us that without making us sit there so long.”

“Macho. Macho. Macho,” Connie said.

“I wonder what Don Howard looks like, you know, without his hat,” Tammy said.

“Oh, don’t get me wrong,” Jeannie said. “He’s a nice looking man.”

What they were doing was really a test of our qualifications. Waitressing doesn’t require specific skills, just a lot of patience. Waitressing at Billy Bob’s is for people who know the company’s time is more important than their own.

Some of the girls got fed up with waiting for Howard to appear and left. Others arrived just in time for the third meeting and got hired without having been at the previous two. At the training session, we were given a list of drink prices, taught how to use a tip tray, and told by Bray that our tips would improve if we gave male customers “just a hint or a hope that you might go home with them.” We were introduced to Barbara Adair, the backstage waitress, who was exhibited as The Successful Cocktail Pro, but Bray and Howard never gave us the chance to ask her any questions. As she sat there in an overstuffed Spanish-American-style chair, she reminded me of a waving, smiling, self-satisfied beauty queen on a tissue-paper float gliding in a parade.

When the meeting adjourned, Howard called us up one at a time and placed us on the schedule. The first thing he said to me was “Can you come tonight at 7?” He was already writing the date and a number 7 down by my name.

“Tonight!” I tried not to seem hysterical.

“Otherwise, I can’t get you on until next week,” he said looking up only as high as my hands wringing nervously and fumbling around with the edge of the table. Okay, I said, sounds just fine.

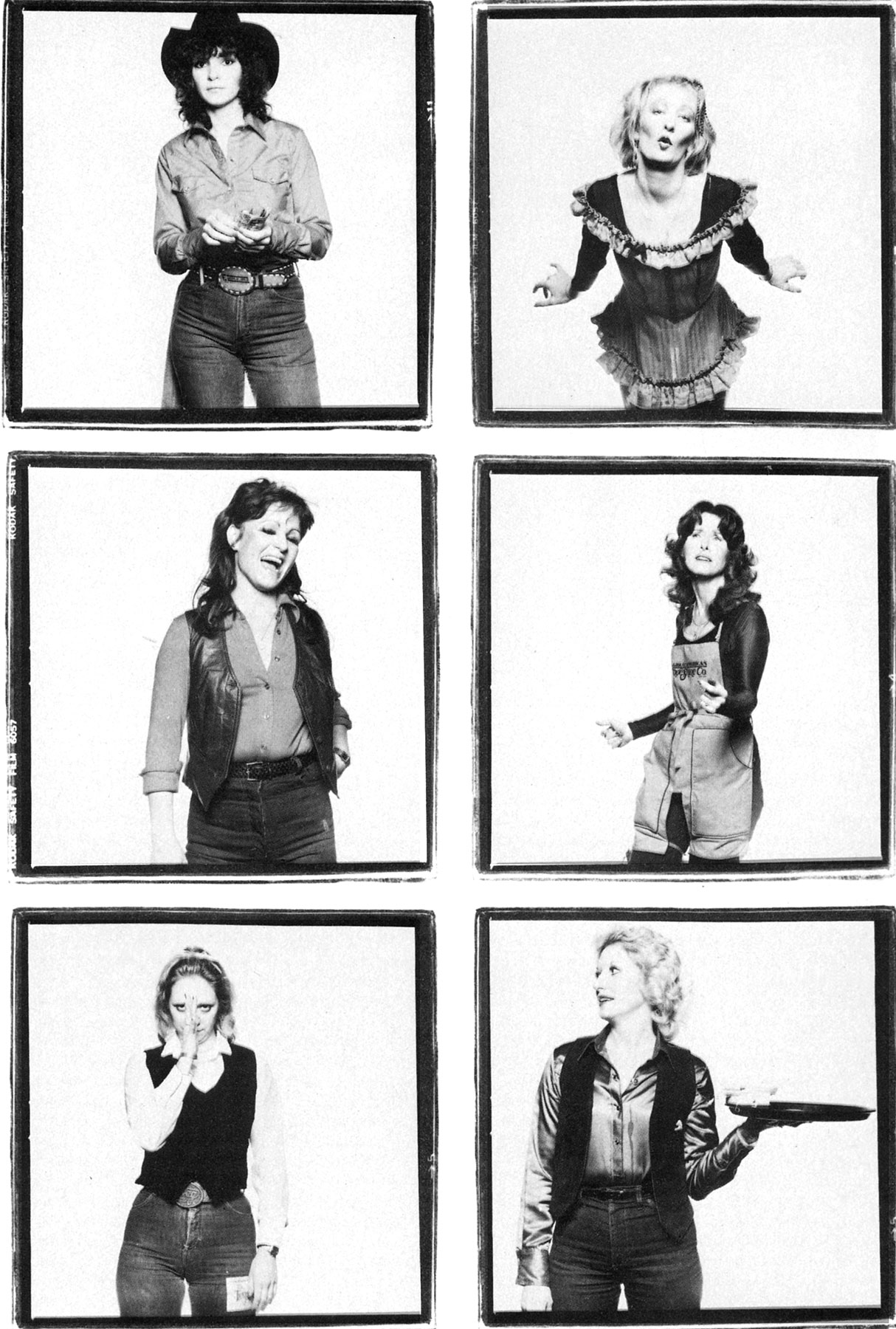

The people working at Billy Bob’s are a little like show people, and they’re at their showiest before going “on,” when they’re behind ominous-looking doors marked EMPLOYEES. The long, high hall extending out beyond the receptionist’s desk gets congested with folks around six o’clock on weekend nights, and for an hour or so, until everyone is assigned a section, it’s like a big, boisterous cocktail party — except no one’s allowed to drink. The security guards (or bouncers) are always big guys, usually weighing well over 200 pounds, and their bodies look as big as mattresses next to the fragile frames of the little waitresses tottering on high heels, holding their serving trays before them like shields. Some of the girls have the faces of angels with features as fine as the feathers in their hair. Others have faces like topographical maps of the Southwest with lines as long as rivers and crevices just as deep. Character actresses in heavy stage makeup — only they’re not acting, they’re for real.

The tension in the back room mounts when the department managers begin to pace back and forth with walkie-talkies pressed to their mouths or their ears. Ahhhh, this is Charlessszzzzpt. Don, are you near the vault? sszzzzpt. And there is a constant current of conversation over the noise of people slamming locker doors and punching in. Casual chatter, shared bits of household melodrama, desperation, little dreams.

All the voices accumulate until the pressure within the employees’ section is so great that it stabilizes the pressure being sensed from outside, and whoosh! the managers delegate their workers to specific sections. Finally we spill out to, as Bray once said, “serve the masses,” leaving peace and quiet in our wake.

On my first night of waitressing, I was assigned a section of tables containing 72 seats, all of which were open to the public. Reserved-seat sections often contain higher tippers; the waitresses with the greatest seniority, the highest heels, or the sexiest hairdos are stationed there. I opted for comfort that night and wore construction boots. Thusly, I was no glamorous babe my first night at Billy Bob’s, and my section seemed to suit me well. I think it could be best described as roughly equivalent to the area for “groundlings,” the penny-a-seaters, at the Globe during Shakespeare’s time. But I had to hand it to them: Those people could consume. I spent much of my time taking used nacho trays and popcorn bins off sticky tables. The line for drinks at the waitress station was so long that it sometimes took up to 15 minutes to get service, and I had yet to learn how to alternate the other bartenders working up and down the aisles. At one point, I returned with an order only to find that the customers had walked up to the bar and purchased drinks for themselves. On another occasion, I delivered six Lone Stars to a table while the man who’d ordered them happened to be in the men’s room. “He’ll be right back,” his wife said. I made a mental note to pick up the $9 due and then forgot about it; one foul-up like that can ruin a waitress’ night.

I had all the wrong answers and none of the right comebacks. One customer put his arm around my neck (the music was always so loud, I had to hunch over to hear) and said, “Tell me this, hon, do ya’ll have hurricanes?” Assuming he was one of the countless conventioneers, I thought a moment, then said that I knew we had tornados, but that I didn’t think hurricanes ever came this far north. He had meant the drink, not the phenomenon.

People don’t really drift in and out of Billy Bob’s. When they come in, they’re usually there for the night. That means they might sit in the same chair for six or eight hours, and that means they’ll most assuredly get drunk. Confusing orders from drunks were excruciating things to organize. “Okay, ’nother Bud,” would be a typical beginning followed by, “Charlie, what are you drinking? Okay, that Bud and then a Weller and Coke, then ahhhh … ’nother Bud, a Coors Light, what’s that? A Bud. That’s three, four more Bud, a margarita. A Miller Lite, ’nother Lite, and one more Bud; that’s three, four, five Bud. Oh, and she wants that Weller and Coke in a large glass.” I’d be writing all this down fast and furiously, then on my way down the aisle to the waitress station, I’d get caught by someone complaining that their gin and tonic didn’t have a lime. As a rule, all the limes were stocked at the 16 bars near the front of the club, as many as 95 paces away.

Within two hours, my healthy, happy section had thinned down to a small number of discontented drunks needing cigarettes and service much faster than I was capable of giving it. When Brenda Lee sang “I’m sorry, so sorry” that night, I commiserated.

Things settled down about 1 a.m., after the last rodeo show in the bull arena, and I had the time to wipe down one table and listen to a conversation between two men in their 20s sitting about 8 feet away.

“You know, that girl looks like a schoolteacher.”

“Uhmph, yeah. Short hair.”

They were talking about me.

I retreated to the waitress station and considered adding a wig and a padded bra to my expense account. Later, in the ladies’ room, I gave myself a thorough once-over. Even in my shirt still stiff from the hanger at Cutter Bill’s, I looked too much like a woman bent on a career. In the four years since I’d graduated from college, I’d cultivated a no-frills, let’s-battle-this-out-in-the-board-room-boys look that worked well in Dallas but was failing miserably here. In looking around the club at the best waitresses — the girls that made more than $90 on a good night — I noticed that they all carried a magical kind of confidence, a sensuality that I would have to imitate if I hoped to do well.

Every Saturday night (actually 2 a.m. Sunday), after the sounding of “last call for alcohol,” and after the customary playing of “Your Place or Mine?” the waitresses were responsible for “breaking the club down” from Phase IV to Phase II. This means that after cleaning our own sections, we were obligated to disassemble dozens of folding banquet tables and stack hundreds of chairs to make room for the stage’s advancement about 40 yards deeper into the club. That way the club could economize by using only a portion of its available space during the week. I’d been warned ahead of time that “breaking the club down freaks the new girls out,” but I wasn’t prepared for the kind of work we actually had to do. Some of the girls got pretty good at disappearing into the ladies’ room around table-disassembling time. They soon found out that their lazy ways were doing more harm than good; getting ostracized meant that no one would help you if you got in a tight spot.

My second night of work fell on a Friday. Jerry Lee Lewis failed to pack the house. This was the first night of work for Jeannie, Connie, and Tammy, my friends from the training sessions. They were jittery and apprehensive; I, on the other hand, had vowed to be more approachable and carefree, less stuck-up and scared. Unfortunately, I was assigned to a section of reserved seats that went unsold all night. Don Howard came by the waitress station at 10:30, collected the starting bank of $20 he’d given me, and told about seven of us that we could go home. For the girls paying $2.50-an-hour for baby sitters, a night like that is a money-losing proposition. Disastrous.

But when I met Jeannie by the lockers in the back hall she seemed relieved that she was getting to slip away. I asked her to have a drink with me. No, she said, she needed to get home. Please, I said, just one.

A few minutes later, with our coats falling backwards and inside-out over the bar stools, Jeannie and I were sitting up straight with our elbows on the rail.

The bulk of our time, that 95 percent, seemed so loathsome because it consisted almost entirely of, in the waitresses’ vernacular, “taking shit.”

She told me her husband drove a truck. They had a 12-year-old daughter. Jeannie had a clerical day job with a computer programming firm. Her husband had left her a few years ago and moved to Mississippi. “I was just getting used to being on my own,” she said, “when he came back, and I wasn’t ready for him to come back. I wasn’t ready for him to come back at all.”

She didn’t like this waitressing job already, she said. Too much noise. “I was thinking I could do it, but I’m not so sure now if this is for me.” I walked to her car, suspecting I’d never see her again.

Back in the club, thinking I hadn’t gotten much out of my first covert interview, I bought a slice of pizza and walked down toward the stage where Jerry Lee was in full-tilt — banging on the piano keys with his feet, his elbows, and the backs of his thighs. He slid up and down the keyboard as if he were on skis.

Mesmerized, I chomped down on the last bit of crust, glanced to my left, and noticed a tall man standing confidently with one hand resting on the reserved-seat rail. He’d been pointed out to me before. It was Billy Bob. Billy Bob. Standing there with a glass in his hand, chewing ice cubes, just watching.

What began to disturb me about this secret project was the effect it was having upon the rest of my life. Standing in line at the grocery store skimming magazines, calling in to my Dallas office for messages, carrying on conversations with friends — suddenly everything seemed lackluster. But at Billy Bob’s, there were big-name acts on stage, drunks waving their hands in the air for service, big feelings, big crises, booming music, fights, people practically fornicating on the floor. All from just existing, just from being there. Dodging people in the aisle, obsessed with my mission: delivering drinks.

“Two Weller and Coke. One scotch and water. One bourbon and water. A Bud. Two Lone Star. A Lite and a draw.”

It was poetry. And you never knew when you were about to make a big score. It happened when you least expected it. Nothing was predetermined. Nothing was truly under your control. A man might roll out a $50 bill for a single drink. Keep it. Keep it. One of the bartenders told me that Billy Bob gave her a $100 bill once for bringing him a $10 roll of quarters. Another waitress received half a torn $100 bill when she delivered a man’s first 7-Up; he gave her the other half at the evening’s end. When she got home, she said, she very carefully taped the two halves together and stared into the face of the bill for a long, long time. Something like that happened to everyone at one time or another. What you had to do was forget about it happening. Then it would come. Keep it. Big money thrown into your face for nothing except all the time you’d put in getting stiffed and pretending you didn’t care. Here baby, it’s yours. You deserve it.

George Bray had warned us that 95 percent of our time would be spent preparing to make money. I figured that only one-hundredth of the remaining 5 percent was when the big tips came, the other 4.99 percent resulted in small bills or quarters, depending upon how capable you were. But the bulk of our time, that 95 percent, seemed so loathsome because it consisted almost entirely of, in the waitresses’ vernacular, “taking shit.” Bowing down to the assigning manager, bowing down to the head waitresses, bowing down to the customer. Waitressing is smiling when someone jerks you violently by the arm and says in the surliest of sneers “bring me another shot of Jack.” It’s smiling when the manager moves you to another section that you know he knows no one wants. It’s smiling when another waitress who has absorbed her share of grief for the day says, “Hey, I was waiting here before you.”

“Not taking any shit” is a waitress’ crusade, and it’s the subject of most of their conversations. Despite that, it continues to come in from all sides, perhaps because they fight it laterally instead of rising above.

Once I was watching the spotlight operators climb to their posts before the first of two Roy Clark shows when a waitress named Candy materialized behind me and wanted to talk.

“Something’s wrong with my damn transmission,” she said. “I called AAMCO this morning, and they towed my car to the shop for a free estimate. You know, if it’s free, I figured, why not? And if I don’t like the estimate they give me, I’m going to take it somewhere else.”

I said something like, “That sounds wise.”

“I’m going to say that the price sounds unreasonable,” she went on, “and then I’m going to take the car somewhere else, that is, if I don’t think the first price is fair. I’m getting pretty cranky in my old age…”

“Well, yeah. It happens.” I really wasn’t paying much attention to her. A man on stage was communicating with the light operators through earphones.

“I’m sick, just sick of letting people take advantage of me, you know? And I’ve decided that I’m not going to take any shit from people any more. People will walk all over you if you let them, and I’m just not going to take it any more. You know, enough is enough. Right? I’m no dummy. I’ve just decided ’no more.’” No more.

We didn’t speak for a few moments. Then suddenly she said, “Last night I was so mad at my ex-husband that I threw my boots at him, and they made two dents in the apartment wall.”

I said, “I thought you weren’t going to take any shit any more.”

“Yeah, yeah. He’s real bad news. He’s nuts. And I married him twice.”

The nicest people around the club, the people who troubled us the least, were the security guards, although now that I think about it, their intentions might not always have been so honorable. Ladies and gentlemen, please move out of the aisle. We’ve got to let the waitress through. There you go, doll.

The managers never seemed to have much respect for waitresses as a breed, but then, a lot of the cocktail waitresses didn’t have an inordinate amount of respect for themselves. The owners — Billy Bob Barnett and Spencer Taylor — didn’t have much contact with waitresses outside the VIP Room, but I suspect they perceive waitresses as a homogenous mass.

All the men working at Billy Bob’s made a big deal about how busy they were. My feelings for Don Howard, our manager, kept changing; it’s hard to dislike anyone who always calls you “dear.” There were so many waitresses on his staff who perpetually disappointed him with poor attendance and feeble excuses for having missed work (“My husband wouldn’t let me come,” “My sister came into town,” “My car broke”) that it really took very little to please him. Before long, he was placing me right beside the stage, and more experienced waitresses were jealously introducing themselves and asking my name. By that time I had purchased earrings the size of elaborate fish lures to compensate for the shortness of my hair. I had also learned to wear a leotard under my Western shirt, which I kept open to the waist, and I was tying a $3 bandana tightly about my neck. I’d abandoned the construction boots. I could afford to be relaxed and pleasant with Howard; I didn’t need the money I was making.

Sometimes, Howard would tell us how satisfactory we were as a group; other times he would vent his frustrations on us. There were waitress meetings every Saturday night in the bull arena after closing. Once, balanced on the top rail of the ring with his boots hooked over the second rung, Howard bawled us out from under his black hat.

“You know, I don’t ask much of you girls, and I’m getting real tired of you always letting me down. Last Sunday, after I’d given ya’ll that big talk about coming in when you were scheduled, only five waitresses showed up for work. That’s right, only five. And then that makes me look real bad in front of everybody else, and they start askin’ me, ’What’s the problem with the waitresses?’ I don’t know what to say to ya’ll except that maybe a lot of you don’t know what it’s like to work at most of the clubs in town where the managers want to sleep with you before you can get anywhere. That’s the way it works most places, and we don’t do that to ya’ll here, see. But maybe you don’t know what it’s like everywhere else.”

After this particular tirade, I was among the last waitresses out of the arena, just behind a waitress and her security-guard husband who’d been standing beneath the bleachers waiting, probably where Howard couldn’t see.

“No way you’re going to take that from him,” the guard said, pulling his wife closer to him by the edge of her jacket. “No one talks to my wife that way.”

“Aww, honey,” she said. “Don was just pissed.”

There’s something about working in a bar that establishes you almost immediately in a brotherhood, or in this case, sisterhood. In the dimness of the bar light, the edges of things blur, and you begin to feel as though you can grasp the essence of someone’s being within a few conversations, sometimes in just a few words. There’s a flatness to everything. And people come and go so fast, there’s never any time.

One night, I was standing in the waitress station waiting for my section to fill up and drinking ginger ale on the house when another waitress I knew only by sight came up to the bar and just stood there. Our eyes met for a moment, then we fell back into our respective reveries. Out of the corner of my eye I saw her look at her watch and twist it straight on her wrist. Then she stood very still. I turned around so that my back was resting on the bar and so I could face the interior of the club. I took a sip of ginger ale and a bite of an ice cube, then inclined my head to the right, raised my eyebrows and exhaled as if to say, Well, here we are; this is dull. She continued to face the bar, which I figured was her way of expressing closure. If she’d turned around to face the club, I would have known she wanted to talk. Finally, after what seemed like an interminable period, she made one remark, and she said it as if it were just a statement of fact.

“I’m lonely,” is what she said.

I shifted my weight and looked at her. She was looking right at me, but her eyes were saying, “Don’t say anything. It’s no big deal. It’s just true.”

Every now and then, and with greater frequency as the weeks went on, I’d get a little antsy, a little nervous about my role, and I’d tell myself I’m only here to absorb it. Take it all in.

But I really couldn’t help but get involved. I really couldn’t help but hurt. It surprised me every time I found myself listening to a waitress’ life story just as some song with a mournful pedal steel that paraphrased what she’d been telling me flowed through the speakers above our heads.

And I could see them in different stages — as if all the waitresses were tadpoles, but some had tails and others had feet.

Among the youngest was Frannie, who was married to a Billy Bob’s bartender. I caught them kissing once in an empty waitress station. They parted, and he swaggered back behind the bar to make my drinks.

“Baby,” she said as she rested her weight on the front of the bar, “if we make a lot of money tonight, can I put that jacket on layaway?”

He didn’t answer.

A week later, I saw her in the ladies’ room. We didn’t speak directly to each other; we spoke into the mirror.

“I sure wish I could go home,” she said. “I feel sick.” She spread her hands out over her stomach and made a diamond-shaped configuration with her forefingers and thumbs.

“Pregnant sick?”

“Maybe,” she said.

“Is that good?”

“Well, we talked about it quite a while ago, and he said he didn’t want one. Then the next day he told me that he’d thought about it, and he’d changed his mind.”

I asked her if they had enough money to have a baby. She exhaled a huffy little laugh and said no.

“What are you going to do?”

“You don’t need money to have a baby,” she said in an aren’t-you-a-silly-person voice. “You just need to want a baby. If we waited until we had a million dollars to have a baby, we’d never have one.” Then she gave me a sweet, half-confident smile.

This was not the only time I realized there were irreconcilable differences between me and the other girls. One night Connie, Tammy, and I ate in the Waffle House on the Jacksboro Highway. “I’ve never had a bad meal in a Waffle House,” Connie said, unfolding her napkin. She asked Tammy what her name was going to be when she married her fiance next year. Tammy told her and said, “I really kinda like my old name, to tell you the truth.”

I phased in. “Why not use your maiden name?”

Tammy’s eyes widened. “Oh, sure.”

“Oh yeah,” said Connie. “Some people do that. They keep their maiden names legally and everything. Career women do it. Women who have, you know, careers, do it. It’s very big down here.”

“Yeah, right,” Tammy said. “That would go over great with Tony. I can just see his face. He’d die.”

I never worried much about Tammy. She was headstrong and streetwise and about to get married to a man who didn’t look too bad. (“Hey, he is hairy,” said Connie when Tammy showed us his photograph.) Tammy never wore makeup and had skin like varnished oak.

It didn’t take Tammy long to get disillusioned with the $30-a-night she was making as a cocktail waitress. One afternoon she had a conversation with one of the Great American Shoeshine girls working near the VIP Room. “Those shoeshine girls make a fortune!” Tammy reported back to Connie and me. “Over $100 every night. We should all change over.” But Connie didn’t like the idea of stooping over somebody’s boots — that’s what she said; but what she probably realized was that she didn’t have the ooomph it takes to polish, wipe, and buff a man’s boots in the erotic manner those shoeshine girls do.

What people come to find at Billy Bob’s I never discovered.

Connie’s life was considerably more complicated than Tammy’s. Connie was 29, had two babies, and was married to a man in the building business who had a drinking problem and who didn’t want her to work. Her dream was to get back into a bluegrass band. Her husband had made her give up music.

“But now, see, I’m scheming,” she once said. “I never should have gone back to him the first time we split up. But I’ve figured it all out now, and I need to find a job that will pay me at least $7 an hour so I can take the kids and move out on my own.” She wanted to find a factory job, she said. She liked piecework.

Connie’s attendance record was fairly disgraceful because her husband often wouldn’t let her use the car. One Friday night she decided to “freak him out” by not going home at all and spending the night at a girlfriend’s. “That way, I’ll keep the car all day and be able to get to work Saturday night. He’s good with the kids, so they’ll be okay.”

Connie failed to appear on Friday of the following week. I saw her for the last time that Saturday, just as I was heading out of the back room. She waved from the far end of the hall and walked toward me. I remember thinking it was strange to see her wearing glasses. Then I saw her black eye.

“This is nothing. It was a black face. Now it’s just a black eye,” she said. She was smiling.

I’ve seen Billy Bob’s in the daylight only once, and that was on one unusually warm but overcast December afternoon after a meeting about how the club was going to deal with the Big Night, New Year’s. A waitress named Vanessa and I were walking through the parking lot toward our cars when she stopped rather abruptly and said, “Where do all those fences go over there?” She was looking right at the stockyards. Then we both noticed some people on the stockyard walkway, a bridge suspended about 30 feet in the air. “Neat! Let’s go up there.”

A few sets of stairs later, we were looking at the Fort Worth skyline on the left and the Billy Bob’s marquee on the far right. Below us there were, of course, lots of cows. As she walked the length of the overpass, periodically pushing the hair out of her eyes, Vanessa told me that she had an education degree from a college in Missouri and that what she really wanted to do was teach. I asked her why she was working at Billy Bob’s. She puffed out her cheeks then exhaled through her nose.

“Well, you know, I hardly feel like I’m really working here. I’ve applied for a substitute teaching job, but I don’t know if I’ll get it this late.

“Waitressing. I don’t know. I’ve waitressed before,” she said. “It’s just … it’s just something. You really don’t have to commit yourself to it. I mean, there are minimal demands, so it works while I’m trying to move out of my sister’s place and kind of establish myself.”

Then she said something like “It’s funny when you leave a waitressing job, especially in a big place like this because they all say ’Who was she?’”

I could barely hear her because she was talking with her head bent down.

“What?”

“‘Who was she?'” she said, lifting it up. “That’s what they’d say if I quit today. Don would say, ’Vanessa quit.’ Then somebody would say, ’Who was she?’”

During four and a half weeks I worked 13 nights at Billy Bob’s Texas, and in that period of time, about a quarter of the cocktail-waitressing staff quit. December is notorious for being the worst of all months for most restaurants and nightclubs, and some of the girls got frustrated with the paltry sums of money they were pulling in. Five waitresses out of 45 quit after the Roy Clark show, which was a success for the club, in terms of ticket sales, but a bust for the waitresses because so many of the old-timers drank soft drinks and didn’t tip. Two girls scratched out their names and wrote “I QUIT” directly on the posted schedule right after that.

What people come to find at Billy Bob’s I never discovered. It is too large for single people to successfully mingle in, and I’ve been told the “action” in Fort Worth is elsewhere. Obviously, the music was always a draw, and the country acts attracted families — Mom, Dad, an older son and his wife was not an unusual combination. More married couples in their 30s and 40s come to Billy Bob’s than any other group outside the tourists. They come in two varieties: happily married and not-so-happily married. The happy ones might get drunk and neck. The unhappy ones argued. It was sometimes entertaining but usually disturbing to be hailed by the husband and shooed away by the wife. That happened at least once a night, and it always posed a problem. Obey her and be thanked, or obey him and get tipped, usually quite generously.

Of course it’s safe to say that people flock to Billy Bob’s to have a good time. What constitutes the “goodness” or the “quality” of the “meaningfulness” of their fulfillment is another issue, but eventually I saw that everything connected, that there were distinct correlations between how well I was working, how happy customers were seeming, how attractive I was feeling, and how much money I’d made. A lot depended upon the enthusiasm of the musicians on stage.

When Billy Bob’s was really clicking — when customers and employees seemed to be cooperatively moving toward a common end — you could feel it as powerfully as you’d feel an electrical charge. It pulsated from the stage.

By 10 or 11, the bartenders could move as fluidly as the liquor they poured. They’d find an inner rhythm and vary it slightly to suit the nature of the song being sung on stage.

These were the times, the uplifting times at Billy Bob’s, that the waitresses were energized by little bursts of self-esteem. Suddenly they were vital parts of a beautiful gymnastic routine. Money was coming in. It was lyrical, perfect.

The service at Billy Bob’s was just that smooth on New Year’s Eve when some 4,000 patrons paid up to $250 apiece for drinks, a lousy breakfast, cheap sparkling Italian wine, and the best all-purpose entertainment lineup in the country that night. Bob Hope (who is said to have made $100,000 for three hours on stage), Johnny Cash, June Carter Cash, Tanya Tucker, Chuck Berry, Razzy Bailey, and the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra.

One-third of the customers were servicemen in uniform who came on donated tickets. That lent a certain USO eerieness to the extravaganza.

At midnight, balloons were dropped, and all the celebrities got up on stage to sing “Auld Lang Syne.” I had a controllable group of likable customers tipping me $20 bills. They were potted by midnight, of course, as were the bartenders and many of the waitresses.

Soon everyone was singing a raucous rendition of “Roll Out the Barrel,” led by Tanya Tucker. Johnny Cash was standing next to Bob Hope, and both of them were singing and gazing affectionately at June Carter, who had enthusiastically hiked her beaded evening gown over her knees so she could wiggle and dance around.

All the servicemen sang. All their wives sang. All the wealthy-looking Texans in their handsome hats and horseshoe-shaped diamond rings clapped their fat hands together and sang. Everyone was singing, and there was very little else I could do but find a vacant chair to stand on and sing along, too.

Roll out the barrel

We’ll have a barrel of fun

Roll out the barrel

We’ve got the blues on the run

I stood there — engrossed — knowing I was enjoying what I heard and saw, but wondering what the hell I was supposed to be getting out of it. What did it mean? I was grasping for available stimuli, hoping something would be triggered. Nothing was coming up. Scratch. So I decided not to try. It was, after all, just another New Year’s, and I’d never seen anything quite like it before.

I hugged my tray and sang until someone pulled me by my belt loop. I’d forgotten who I was. I looked down. It was a man I’d never seen. He seemed irritated. He said, “Can you bring me two double shots of Crown?”

Author