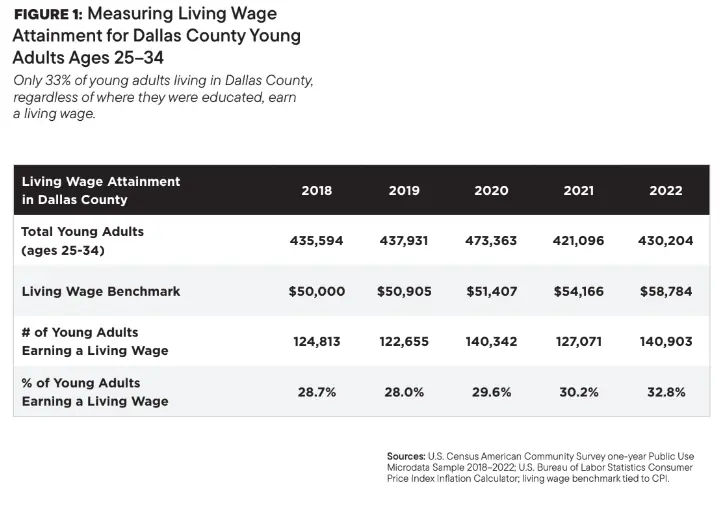

Last month, the nonprofit Commit Partnership released a report that found that 2 out of 3 young adults in Dallas County do not earn what MIT defines as a living wage according to its calculator, which is used by local governments and employers to determine pay. With the report, the organization made its own commitment to invest in an effort to reduce that number to 50 percent over the next 16 years.

The solution, education advocates say, is a two-pronged approach: make sure students who wish to attend college are ready to do so, and provide others who aren’t headed to college access to training to qualify for the high-paying jobs Dallas companies are trying to fill.

This isn’t a new conversation. I recall about seven years ago, two executives with the Dallas Builders Association detailed a plan they felt would help their industry find more reliable skilled workers. Plumbers, masons, framers, and the like were in such short supply that builders were spending an added $4,000 to build a home. It was difficult for contractors to keep job sites staffed as workers were enticed to other projects with more pay.

One way to solve that problem? Boost the local labor pool. At the same time, Dallas ISD was planning programs to teach its students the skills that would land them a high-paying career even if college wasn’t in the cards. Michael Turner, who was then president of the Dallas Builders Association and a Dallas ISD parent, was encouraging the district to partner with local companies to provide more career training. It was a win-win: with the right training students could graduate either licensed in some trades or almost ready to be licensed. It requires being honest that college is not the right fit for every student.

“They could get great paying summer jobs while they’re in high school,” Turner told me. “And if they go to college later, they have a great job they can do in the summer to keep student debt down.”

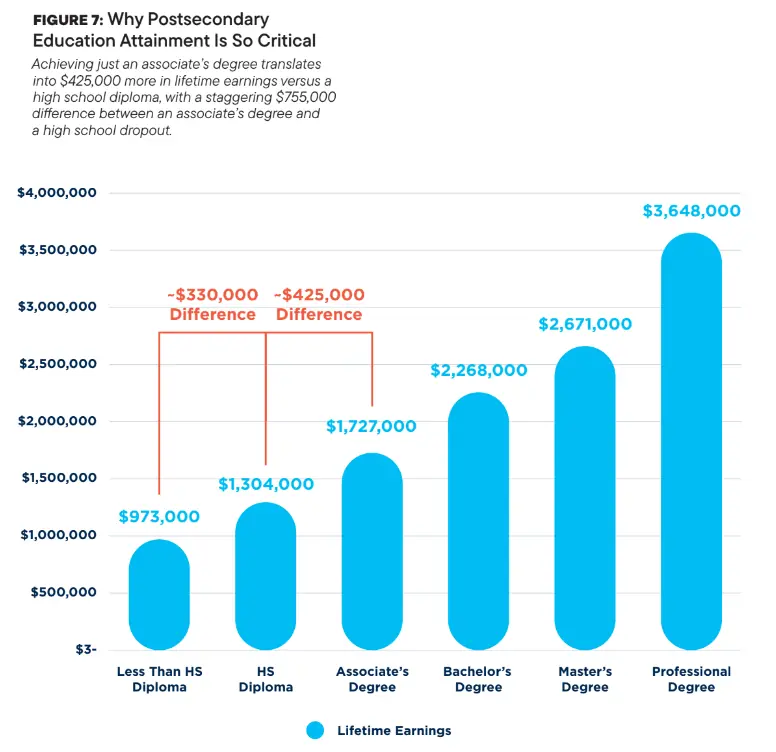

Efforts like the one Turner described may boost the local economy in ways beyond having a steady supply of highly trained, skilled workers. Commit’s report found that when Dallas students are given the opportunity to complete even two years of college, their earnings increase exponentially. Dallas County high school graduates between the ages of 25 and 30 who have some form of college degree (associate’s, bachelor’s, or an advanced degree) collectively earn, on average, almost 60 percent more than a young adult without a degree. Over their lifetime, they can earn over $755,000 more, which equals almost $13 billion more in economic gain among each graduating class.

Commit’s report found that when Dallas students are given the opportunity to complete even two years of college, their earnings increase exponentially.

The number of Dallas County young adults making a living wage is growing, thanks in part to these changing approaches to education. In 2018, 28.7 percent of young adults made a living wage. By 2022, that number had crept up to 32.8 percent. But that isn’t as much growth as most would like. The county ranks seventh in the U.S. in its number of young adults living in poverty out of 3,100 counties nationally. It’s sixth in the nation in the number of children living in poverty.

At a recent panel discussion about the report’s findings, Dallas ISD Superintendent Stephanie Elizalde said the data in Commit’s report should also serve as an inflection point for everyone involved in educating and employing Dallas’ young adults. She believes the district is one of the most critical economic engines for the region.

“Our entire community really needs us to do a better job to ensure that our students have the ability to fill jobs that go vacant,” Elizalde said. “Not just any job, but jobs that require high skill and are high demand and that pay high wages so that we can, in fact, be the hand that lifts our students and their families out of generational poverty.”

In 2024, Dallas ISD’s efforts to improve graduate college and career readiness have grown substantially. There are now three career institutes (with a fourth due to open in 2026) serving several high schools. The campuses offer 16 different career study opportunities that give students the chance to earn professional certifications that will allow them to start a career right out of high school. Those include cybersecurity, construction and carpentry, electrical and solar technology, dental assisting, architecture and interior design, game design, plumbing, and welding. A health science cluster offers the opportunity to become a dental assistant or EMT. All the courses were created after consulting and partnering with local companies that constantly seek workers.

But the district is also focusing on college success, too. It offers dual credit courses and collegiate prep academies that will allow students to graduate with a high school diploma and an associate’s degree—for free. Elizalde said in the last five years, Dallas ISD has graduated about 50,000 students, and nearly 10 percent of them have either an associate’s degree they earned in high school or more than 60 college credit hours.

That support also comes from partnerships like Dallas County Promise, which is helmed by Karla Garcia, a former Dallas ISD trustee who also graduated from a Dallas ISD school. The district is working with Dallas College to allow students to earn dual credits while attending high school, which gets them an associate’s degree along with their diploma. All four say that those efforts might move the needle, but more investment will be needed to ensure that more students graduate high school ready for college or a career and, should they choose college, are supported enough to stay enrolled.

Garcia’s program helps students figure out their postsecondary school options, which is why Dallas ISD offering multiple pathways to a living wage excites her. Her program, along with the district’s investment in extra counselors, aims to help students make the leap from high school graduates to full-time college students.

That support is important. Commit’s report identified two places where students are more likely to lose traction: the period from middle school to high school graduation and then again in the summer between high school graduation and the start of the college school year. Elizalde hopes programs like the career institutes will also improve the district’s dropout rate.

Right now, about 19 percent of Dallas County eighth graders don’t complete high school. Elizalde said giving them sound reasons to stick around—and telling them what they’re learning will help them earn more money—could be a key to addressing Commit’s findings.

“We want them to know it’s OK to work at McDonalds. But it’s not enough for them to work at McDonald’s as a server for the rest of their entire life,” she said. “When I’m a high school student, and I think that is all I can hope for, then I may be more likely to go, ‘Hey, why am I going to get a high school diploma? What doors does it open?’ Because the high school diploma today by itself does not open the doors that it used to open.”

Elizalde sees the career institutes, as well as an array of programs at Skyline High, as reasons for students to stay in school. “This is hands-on, tactile learning for students who are gaining and developing knowledge and skills that are going to set them up for success,” Garcia said. “I think we’re going to see that dropout rate decline in the coming years as students get to see that, ‘Oh, I can learn this, and I can use it this weekend at this job site.”

A child of immigrants, Garcia developed a love of learning and found support for her college plans in high school. At the time, there were no affordable four-year options locally, so she left the state for college then returned after graduation to work in education in Dallas County.

“You cannot gift a young person who has dreams and aspirations anything greater than there is a pathway for you after high school,” she said. “And not only is there a pathway, but it can be made more affordable, it can be accessible. And at the end of your hard work, there’s an opportunity for you to take care of yourself and your family.”

Dallas County Promise helps students remove barriers to attending college. Keeping them there becomes a collective effort. Dallas College Vice Provost Tiffany Kirksey says the system has focused on removing barriers to continuing toward a degree. That support includes food pantries, DART passes, clothing closets, and even laptops. In the case of Dallas ISD students enrolled in dual credit programs, tuition and books are also included.

Kirksey said Dallas College has also worked to ensure its graduates are prepared to transfer to four-year colleges. Nationally, 80 percent of students say they want to transfer to a four-year school, but “six years later, only 20 to 25 percent of them do indeed transfer.”

Often the likelihood that a student transfers to a four-year school, she says, boils down to being exposed to more opportunities. The more opportunities offered to the student, the longer the student remains in school, which could change their goals later in life, too. Dallas College is collaborating with four-year schools in the area to make the transfer process more seamless and degree plans easier to shift should their goals change. “We take what’s a really complicated puzzle and simplify it to ensure that they can move along their journey.”

Students are introduced to six different, intertwined paths, Kirksey said, all of which are designed to help a student obtain a job in a high-demand field and earn a living wage.

These extra efforts rely on funding. Legislators in the last session allocated more money for community colleges whose students complete their degree program or transfer to a four-year college. But there hasn’t been an increase in the state’s per-pupil spending for public school students since 2019. Education advocates and school districts are watching warily as the debate around school vouchers is poised to ramp up again in next year’s session. They’re also watching what the Trump administration may do—changes to the Pell Grant allocations, how federal financial aid is administered, and other policy changes led by the future secretary of the U.S. Department of Education. (Including abolishing the department, something the president-elect posited on the campaign trail.) All these variables could impact the federal grant dollars available to students wishing to attend college.

But last month, the panelists were optimistic about the impact those early college and career programs were already having in Dallas, and how they would improve the odds that more graduates will earn a living wage.

Perhaps the biggest ambassador for Commit’s argument was holding a microphone at last month’s panel. Garcia said after getting a bachelor’s degree, her first job’s salary surpassed her entire family’s income that year. She can afford to spend now—Scholastic Book Fair books for her nephews, for instance, and trips to the State Fair. Those splurges speak to a career that affords her not just a living wage but something beyond basic necessities.

“I now have nephews who are pre-K students, and the Scholastic Book Fair was there last week,” she said. “When I was in school, the Scholastic Book Fair was the most exciting. There was everything I wanted but couldn’t have.” This year, her nephew could have any book he wanted. “There was not a single thought about what he could have access to because his Tia and Tio and his mother, we can provide that for him.”

“With my wage, a living wage transcends to more than just the paycheck.”

Disclosure: Commit is a client of D Custom, a subsidiary of D Magazine’s parent company that operates independently of the magazine.

Author