Three charter amendment measures spearheaded by the nonprofit group Dallas HERO will appear on the November ballot. Critics say they are unnecessary and likely to “cause harm” to the city if voters approve them. Supporters of the amendments say they will bring accountability to City Hall and bolster the hiring of police officers by increasing pay for recruits.

Earlier this month, City Secretary Bilirae Johnson’s office confirmed that Dallas HERO had collected enough signatures to place the amendments on the ballot. State law requires the city to do so, but councilmembers made it clear they were holding their noses and voting yes on Wednesday night.

“I do think they can cause harm to our city,” said Councilmember Paula Blackmon. “But I will put it forth to the voters and let them decide and have that conversation with them.”

The city charter is the document that lays out the rules for how a city operates. State law requires cities to review their charters every 10 years. The other amendments to the charter—which include moving city elections from May to November, allowing non-citizens to serve on boards and commissions, and giving the City Council oversight of the department that investigates fraud allegations at City Hall—went through a months-long process that started with a citizen commission that reviewed suggestions from residents, and ended Wednesday night. Amendments that go through this repeated vetting and debate have been picked apart, reconstituted, and sometimes even resuscitated over the course of a year. Petition-driven amendments require organizers to collect at least 20,000 signatures from registered voters in Dallas.

So which is it? Are councilmembers merely reluctant to subject the city to more oversight, or are the amendments actually dangerous to Dallas?

First, we can examine the amendments as they were submitted to the city secretary. (What you will see on the ballot changed after some back-and-forth between Dallas HERO attorney Art Martinez de Vara and the City Attorney’s Office; you can read that here.)

The first amendment would allow residents to sue the city if they believe the city isn’t complying with the charter, ordinances, or state law. The amendment would also require the city to waive its governmental immunity to such suits.

The second amendment would require an annual survey of residents that would factor in to the city manager’s pay and continued employment. The measure requires the city to survey at least 1,400 residents, with the results informing whether the city manager gets a bonus of up to 100 percent of their annual salary or whether they get fired.

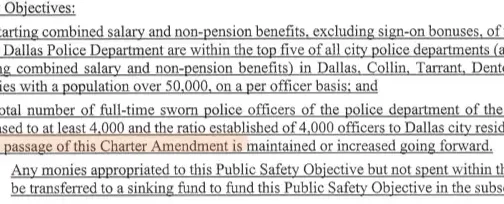

The third amendment is two-pronged. It would earmark at least 50 percent of new excess revenue each year for the police and fire pension system. It would also require that the additional funds go to increasing starting salaries for police officers and maintaining a police force of at least 4,000 officers. (As of this summer, Dallas has just shy of 3,100 officers.)

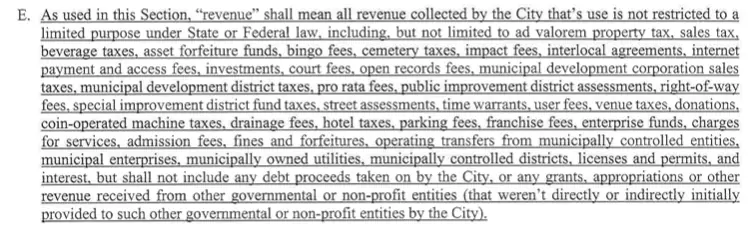

Specifically, the third amendment says that revenue would include more than just property and sales taxes. It would include “all revenue collected by the City that’s use is not restricted to a limited purpose under State or Federal law.” That would include, it says, everything from property tax revenue to asset forfeiture revenue, bingo fees, court fees, open records fees, public improvement district taxes, and hotel taxes.

If any of the measures were to pass, the city would be stuck with them for at least two years; that’s the earliest the city could amend the charter again. And the measures could hamstring a lot that will happen in City Hall between now and election day on November 5. That could include the police and fire pension, the budget, and the city manager search.

Tolbert told the Council that the budget staff will hand them in the coming weeks is now balanced. The Council will vote on it mid-September. But those plans could be thrown into disarray should voters approve the charter amendments.

At a briefing last week, councilmembers were quick to point out the issues they had with the proposed amendments. Words like “draconian,” “drastic,” and “fiscally irresponsible” were used to describe the collection of proposals. Several worried that tying a city manager’s pay and employment to a survey taken by less than .11 percent of the city’s 1.3 million residents would impede its search for a new city manager. Hiring 900 officers rapidly would also be a herculean task and a blow to a budget.

Dallas police Chief Eddie García said he wasn’t sure his department could handle hiring and training 900 new recruits. He acknowledged that attrition chews up a great deal of ground the department gains each year, but that he’d prefer to focus on keeping experienced officers in the department. The city budgets for 250 new officers, he said, but 190 leave. If you do the math, that means it could be 15 years before the city manages to reach Dallas HERO’s goal of 4,000 cops.

Dallas is not alone in its recruitment difficulties. Cities across the country are finding it hard to recruit and retain officers. A 2023 study by the Police Executive Research Forum found a 4.8 percent decline in their numbers compared to 2020. Hiring improved in 2022, the study found, but more officers are resigning than are being hired, something that García has also consistently explained to the City Council.

Next year’s budget, which includes a large property tax rate decrease, would fund 250 new officers to the tune of $30.5 million.

But even if he could find 900 new bodies, García says, the city’s police academy can currently handle only 250 recruits per year. Should the measure pass, “We’d be robbing Peter to pay Paul with regards to training,” he said. It takes roughly a year for a new officer to go through the academy and then field training. “We need to grow slowly. We didn’t get into this mess overnight. We’re not going to get out of it overnight.”

And training isn’t the only hurdle to hiring that many cops so quickly. The department also must consider patrol cars and equipment. City staff estimates that adding another 900 officers would cost more than $175 million. Interim City Manager Kimberly Bizor Tolbert said every city department would be forced to cut services. “There would be no sacred cows,” she warned.

García told Councilmember Omar Narvaez that it would also impact the department’s “weed and seed” program, which works to rid neighborhoods of criminals and then “seed” them with positive opportunities like parks, programs, and libraries. García credits programs like that for helping to reduce the city’s violent crime rate for the third year in a row. If the city is forced to make cuts to accommodate new recruits, it would limit the “seed” García would be able to implement.

One of the city’s public safety unions also questions the necessity of the amendment. The city currently has a “meet and confer” contract with the two main unions for the police and fire departments. That contract sets up a structure for pay increases and benefits, and the pay structure is based partly on pay comparisons to 17 other cities. Recruits make $75,000; Dallas HERO would like it bumped to $85,000. In January, police officers and firefighters are due to get a 7 percent raise, in line with the contract.

That contract came up Wednesday night as Councilmember Adam Bazaldua shared a statement from the firefighter’s union that called Dallas HERO a “rogue group from outside the City of Dallas.”

“While we appreciate the attempt to increase the starting pay of police officers, this group did not consider the fact that we already have a mechanism in place that positively impacts both police officer and firefighter pay across the board,” the statement continued. The union says that police officers and firefighters are currently on their fifth contract, which was passed by 98 percent of its membership in 2022.

Pete Marocco, Dallas HERO’s executive director, says Tolbert and the Council’s concerns are “laughable.” “Kim Tolbert’s spurious allegation that every city agency would have to cut resources is laughably fabricated for anyone who reads the plain english [sic] of the Amendments—so unresearched and lazy, and appears to be deliberate voter disenfranchisement,” he said in a written statement to D Magazine. “The proportion verbatim states the plan comes from no more than 50% of new revenue.”

He also says that he doesn’t “expect many” lawsuits should the city find it difficult to meet the hiring benchmarks in the amendment. He says that “radicals” in the City Council wished to defund the police.

While several on the Council asserted that Marocco’s organization did not talk to the city before embarking on Dallas HERO’s quest to get the three amendments on the charter, he says Dallas HERO did collaborate. “We enjoy our collaborative relationship with the DPD and DPA without division and honor Chief García’s responsible leadership of egregiously thin resources,” he said. “We support a responsible scalable plan mindful of capacity and standards to absorb new officers, and reject defunders’ contrived attempts to portray division, where there is none—we support our blue!”

However, the amendment itself does seem to indicate that the 4,000-officer benchmark goes into effect “as of the date of the passage.” And the amount of collaborating Dallas HERO did with local law enforcement is also a question mark. An official with the DPA said that they would not classify the few conversations they had with the organization as collaborative. Dallas Police Department spokesperson Kristin Lowman said that the department was “not aware of who at DPD he collaborated with—it was not Chief García.”

“To have a community that wants this department to grow is a gift. But, we need to grow responsibly. Acclimating 900 officers in one year is difficult, close to impossible,” García said in a statement to D. “We’re on track to grow, and we appreciate this support, but we must recognize the unintended consequences to the department itself by growing so quickly and having to allocate so much money to simply staffing, not taking into consideration vehicles, equipment and training for those officers.”

Marocco pointed to one organization—the National Fallen Officer Foundation—that backed his organization’s efforts. The letter urged the Council to send the amendments to voters because it would “enhance the city’s crime-fighting capabilities, improve officer well-being, and strengthen community trust.” It was signed by the foundation’s field director, Merlin Lofton. According to the organization’s website, Lofton is a retired 20-year veteran of the DPD. Its executive director is Demetrick “Tre” Pennie, “an active 22-year Dallas Police sergeant.”

At last week’s briefing, roughly two-thirds of the public speakers signed up to support Dallas HERO were from outside the city. Marocco indicated that he was from University Park. Also signed up to speak was Monty Bennett, the publisher of the Dallas Express and controller of Braemar Hotels and Resorts, who also lives in the Park Cities. He ultimately did not speak at that briefing, but he has said plenty in the past about Dallas’ safety. According to press releases from Dallas HERO, Stefani Carter, who also sits on the board of Braemar Hotels and Resorts, is the organization’s honorary chair.

“It’s just weird that somebody from University Park wants to lead this charge,” Narvaez mused last week.

This week, four pro-HERO speakers indicated they lived in Dallas, primarily in North and Far North Dallas. The remaining speakers were either from elsewhere in North Texas, or did not indicate where they were from, including Marocco.

It seems that the Council won’t go down without a fight. Last night, they approved three additional amendments. One would give the Council final authority over city funding, directing it to consider only any instructions in the charter about wages as recommendations. A second states that nothing in the charter allows the city to waive its immunity from lawsuits. Another would put the city manager’s compensation and employment review squarely in the hands of the Council. (In September, a judge threw out those amendments after a lawsuit was filed by one of the petition signers, finding that the language in those amendments was too similar to HERO’s amendments.)

“We must not let our constituency fall for the rope-a-dope from those folks who are outside perpetrating this tale,” Councilmember Carolyn King Arnold said. She and her colleagues were nearly unanimous in their statements that they intended to warn constituents about the amendments.

That effort may be getting an assist from other local leaders. This week, an op-ed signed by former mayors Tom Leppert, Ron Kirk, and Mike Rawlings—and written with input from several other notable Dallasites—addressed several proposed amendments, including the HERO amendments. The three said the HERO measures “would undermine the city’s budgetary management of its police force and unduly interfere with the City Council’s oversight of city management.” Word has it that more opposition from the business community could be forthcoming.

The City Council didn’t have a choice in putting the amendments before voters. State law requires them to place petition-led charter amendments on the ballot if organizers can collect enough signatures. But come November, residents do have a choice—and the outcome may depend on whose ground game is more convincing.

Author