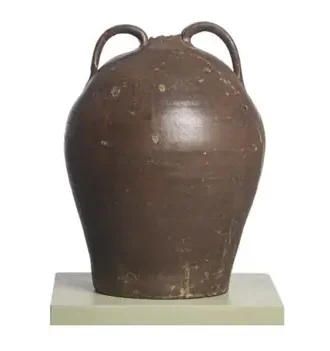

A jug tells the story of the African American Museum of Dallas. Harry Robinson Jr., the museum’s founding director, always wanted a piece made by David Drake. This artist was better known as Dave the Potter, the 19th century Black man was believed to be the first enslaved potter.

“We never thought we’d get one,” Robinson says.

The museum, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this November, has proven time and again that any ephemera important to telling the story of Black Americans was fair game to be acquired and displayed within its walls at Fair Park. No matter how rare.

“Before I die and go to Jesus I wanted a Dave the Potter,” Robinson says. When he found a collector who had one but refused to sell, “I wouldn’t let him out of my office until I got it.”

Indeed, Robinson recounted this story while sitting proudly next to 5 Gallon Jug in the Sam and Ruth Bussey Art Gallery, a room the size of a small apartment. It’s enlivened by a mix of furniture, décor, and folk art made by Black people. To understand why Dave the Potter is a big deal to Robinson, consider this: The 19th-century potter was the first known enslaved potter and also a poet. He was a rebel, too, in both practice and personality. The South Carolinian inscribed his pots and jugs, which was rare because it was illegal.

While he made thousands of pots and jugs during his life, the National Gallery of Art estimates that only 270 remain. Robinson did not disclose how much the museum paid for this one. But one recently sold for $1.6 million in a 2021 auction. The buyer was The Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, founded by the Walmart heiress Alice Walton. Another is currently on display at the Dallas Museum of Art in the performative show When You See Me: Visibility in Contemporary Art/History.

Every acquisition is special and methodical to Robinson, which makes sense for a librarian and archivist, a band of highly organized and diligent professional hoarders. Alongside Dave the Potter’s jug is a spoon by silversmith Peter Bentzson, which is one of only 10 known spoons and 20 flatware pieces in existence, according to the Smithsonian. There’s also a folding cabinet bed by Sarah Goode, who in 1885 became the third Black woman to receive a patent. (“People say she’s the first,” Robinson says. “She’s not.” The first two were Judy Reed and Miariam Benjamin.)

They are three items of the 350 artworks and artifacts in the permanent collection and 60 archives spanning the 18th century to the present. But Dave the Potter is also a big deal because Robinson knew that Dave the Potter was important, and that meant the museum needed one of his works so everyone else could know about Dave the Potter, too.

Robinson speaks confidently, has an opinion on seemingly everything, and knows how to tell a story. He has a contrarian streak and a charming ego.

Robinson has been the museum’s sole executive director since he founded the institution in Dallas in 1974 at the since-shuttered Bishop College, where he also ran the library. It’s had multiple homes, because of both Bishop’s financial instability and a failed capital campaign. After a successful second capital campaign, along with money allocated following a bond election, the museum finally broke ground in 1989 and opened in 1993 in the cross-shaped building in Fair Park, near Grand Avenue.

In his mind, he’s created an unrivaled encyclopedic museum with a vast collection that documents the Black experience by way of textiles, furniture, and baskets, which to more traditional curators may see little use to save or display. “We don’t have any glass—yet,” Robinson says in response.

Random ephemera is the core of any regional museum. They’re repositories for local archives, family heirlooms, and photographs. Scattered through the museum are names of prominent local Black leaders. The solarium is named for former Rep. Helen Giddings. They hold the archives of the original Dallas Express, when it was a Black newspaper, and the Juanita Craft Civil Rights House Collection. But it’s also home to the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame and the archives of Sepia magazine, which started in Fort Worth.

So, while it has the same collection and character as any regional museum, Robinson wanted it to be the grandest Black history museum, a goal befitting of go-big Dallas. Granted, that goal was declared before the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in 2016 in Washington, D.C. Robinson of course attended the opening, was impressed, and toured the White House. He realized his museum’s collection complements the larger one in the nation’s capital.

Folk artists accounted for the museum’s earliest acquisitions in the 1970s, which remain the museum’s largest collections. The Billy R. Allen Folk Art Collection, named for a founding board member, has grown to include more than 500 objects.

Black folk art is the subject of a major exhibition about once a decade. Robinson rightfully doesn’t like the term “self-taught.” It implies someone wasn’t versed in anything at all. The artisans were trained as basket weavers, silversmiths, and potters who told the story of Black life through their work.

“They’re painting from life experience wherever they are,” he says, “and typically use religious symbols.”

One, Sister Gertrude Morgan, thought she was a religious figure herself. “She thought she was married to Jesus,” Robinson says.

In 1976 the museum inaugurated the annual Southwest Black Art Competition and Exhibition, later renamed the Carroll Harris Simms National Black Art Competition and Exhibition in honor of the co-founder of the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at Texas Southern University in Houston. Local corporations donated money to fund the acquisitions.

He’s not done collecting. He mentioned the gaps in the collection. He wants sculptures by Bill Edmonson and paintings by Horace Pippin, among others. He wants to expand the design collection. He wants to curate more exhibitions.

Then he had to end the interview. He needed to call a donor.