Director Oliver Stone put Dallas on the map as a desirable Hollywood film shoot location in the late 1980s and 1990s with Talk Radio, Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July, JFK, and Any Given Sunday. He’s also the subject of my book The Oliver Stone Experience and has been a friend for 15 years.

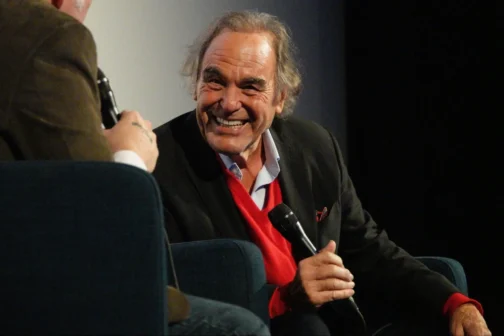

Texas Theatre honchos Jason Reimer and Barak Epstein invited Stone to attend a mini-retrospective earlier this month titled “4 Days in Dallas with Oliver Stone,” which screened his Dallas movies Talk Radio, Born on the Fourth of July, and JFK. Natural Born Killers was also part of the lineup; it wasn’t shot in Dallas, but celebrated its 30th anniversary this year. While he was in town, Stone fit in visits to Dealey Plaza, the Sixth Floor Museum, and the municipal archives beneath City Hall where records related to the Kennedy assassination are kept.

The centerpiece of the weekend was the Oct. 4 screening of 1991’s JFK at the same theater where accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested, and where Stone re-created the arrest with Gary Oldman portraying Oswald. I sat with Stone in the back of the theater, a row behind one of the two seats Oswald occupied on November 22, 1963. When police onscreen spotted Oswald circa 1963 and demanded his surrender, they seemed to be addressing the assembled audience in 2024: a through-the-looking-glass moment.

After the screening, Stone spoke to me onstage about researching and making the movie as well as his personal experience of the assassination and its aftermath. He was 17, and spent the day “watching the coverage, like everybody else.” He didn’t begin seriously questioning the official version of historical events until after the 1974 kidnapping of Patty Hearst, when he read that some individuals involved in the crime had connections to the federal government. “Through the 1970s, I began to educate myself,” he said. Stone became fascinated by alternatives to the “lone gunman” and “magic bullet” theories in the late 1980s, when he was sent a nonfiction book as possible adaptation material: On the Trail of the Assassins by Jim Garrison, who, as the district attorney of New Orleans in 1960s, brought the only criminal trial related to the president’s murder.

“I really thought ‘this is a great thriller,’” Stone said of Garrison’s book. “I hadn’t done the research. I just believed what I was seeing [as I read] was…a potentially great movie.” While writing the script with Zachary Sklar, Stone melded Garrison’s book with Jim Marrs’ Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, and added information he’d gleaned while visiting the film’s primary locations of Dallas, New Orleans, and Washington, D.C. He read the Warren Commission Report and books that questioned it. He talked to historians and former and current officials.

Stone had previously explained in my book, as well as in many interviews, that he made Garrison the main character of JFK because he presented the criminal case against alleged conspirators to kill Kennedy. Stone believed him to be a perfect vehicle to present additional information and other theories about what happened. He admitted that Garrison lost because he “had a weak case” against New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), but added that Shaw “was lying” to investigators and the jury about his connections to the New Orleans criminals and hustlers, anti-Castro Cubans, and members of right-wing paramilitary groups, all of whom loathed Kennedy.

Stone told Dallas Morning News writer Sarah Hepola that reading Garrison’s book while filming Born on the Fourth of July in Dallas may have sparked his decision to make JFK. “I never really made that connection [before], but I’m sure someone took me to see Dealey Plaza for the first time,” he said. “When you see it, you realize what a jewel box it is. How small. You don’t realize that from pictures. It’s a perfect ambush site.”

Various Hollywood and independent directors chose to shoot in Dallas before Stone came to town, resulting in films such as Logan’s Run, Robocop, the 1962 adaptation of the musical Stage Fair, and the horror film Phantom of the Paradise (which will receive a 50th anniversary screening this month at its primary filming location, the Majestic Theater). But it wasn’t until Stone chose Dallas as the location of his claustrophobic 1988 drama Talk Radio—based on star Eric Bogosian’s play, and filmed around the city and on soundstages at Las Colinas—that Dallas hosted a production that felt like possible Academy Awards material, helmed by a director who’d already won multiple Oscars (for Platoon, his 1986 film based on his experience as an infantryman in Vietnam, and his follow-up Wall Street, which got Michael Douglas a statuette as Best Actor).

Released at Christmas despite Stone’s objections (“it was so depressing!”) Talk Radio was a box office disappointment that got no awards traction. But his next project, 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July, about paraplegic war activist Ron Kovic, was a hit that was nominated for eight Oscars and won two (for directing and editing). Born was the movie Stone had wanted to make first in Dallas, mainly because nonunion crews would stretch its budget, but he had to wait eight months until his star Tom Cruise finished making Rain Main. He ended up doing Talk Radio as a time killer and—he said during a post-screening discussion—a way to try different directorial techniques and learn about the city.

For Born, the Elmwood neighborhood of Oak Cliff doubled for Kovic’s hometown of Massapequa, Long Island. Dallas was also briefly home to Syracuse University (faked at Southern Methodist University) and the Miami Convention Center (actually Dallas’ convention center with different signage and some trucked-in palm trees). JFK was the second Stone production to let Dallas be Dallas, and it brought a new level of real-world specificity to its action and dialogue, immersing itself deeply in Dallas’ identity. Where Talk Radio was electrifying for local viewers because of the abundance of recognizable locations and references (a gargoyle-ish rock-and-roller played by Michael Wincott gives a shout-out to “the girls at Valley View Mall!”) Stone’s immense, densely packed JFK—a combination courtroom thriller, detective story, and muckraking work of agitprop–went much further, making the layout of downtown and other parts of Dallas integral to the tale. It weaved in references to actual Texas politicians, institutions, and corporations—including “General Dynamics of Fort Worth, Texas,” cited by Donald Sutherland’s Mr. X as one cog of the military-industrial complex that stopped the United States from pulling out of Vietnam before combat troops could be introduced.

Three of the four screenings were sellouts, which seemed to surprise Stone, and the audiences lined up for good seats well in advance. At the JFK screening, Sutherland’s mammoth exposition dump and star Kevin Costner’s tearful final summation earned rounds of applause.

Stone attended a book signing before JFK, during which he inscribed copies of his memoir Chasing the Light, the JFK screenplay, and The Oliver Stone Experience as well as artifacts related to his filmography and its subjects. He signed a poster for his first directorial effort, the early-’70s horror film Seizure, and November 23, 1963 editions of Dallas Morning News and Dallas Times Herald.

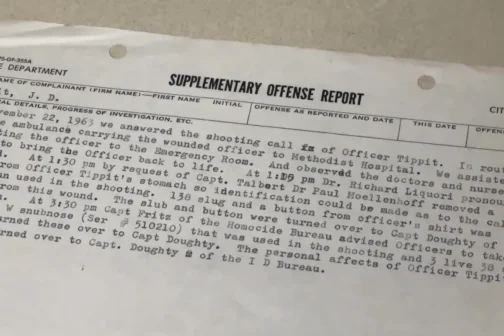

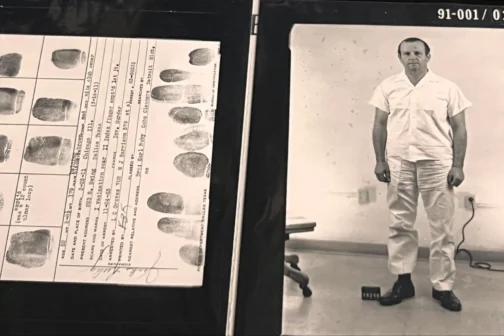

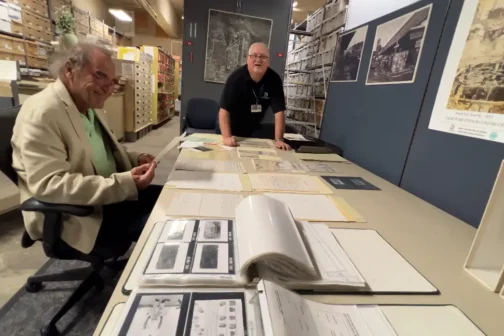

The last time Stone spent serious time in Dallas was 1999, when Jerry Jones let him use the old Texas Stadium to shoot parts of his football epic Any Given Sunday. To my surprise, he said yes to a last-minute offer by city of Dallas archivist John Slate to peruse Dallas Police Department documents and photos from the days following the assassination, including crime scene photos of the book depository and the spot where Oswald shot officer J.D. Tippit in Oak Cliff, arrest sheets, fingerprints, and mugshots of Oswald and his killer Jack Ruby.

The only time when Stone could fit in a visit was a Saturday morning when the archives were officially closed, so Slate met us on a street corner near City Hall. He drove us into the parking garage and escorted us into the guts of the building, a sequence of events that would’ve fit right into the shadow world of JFK. Slate and assistant city archivist Kristi Nedderman had laid out some of the archives’ holdings on a long table. The two alternated showing Stone certain items with their own commentary and letting him sit quietly and flip through materials, which are kept in protective sleeves, at his own pace. (Copies can be viewed online here.)

Slate said the archives began in the late 1980s as a part of the city secretary’s office. The “original stash” of the JFK records was rediscovered in the police department “around 1989. We already had the bulk of the records, and although I don’t know all the details, right after [Stone] finished filming there or during the time he was filming there in 1990 and early 1991, the City Council got rather excited about whether they had done due diligence to take care of whatever was in city departments related to JFK,” Slate said. “A City Council resolution was passed in early ‘92 that all departments were directed to send JFK-related materials to the municipal archives.”

The JFK collection now contains more than 11,400 items that took two years to catalog, annotate and preserve, under the direction of Slate’s predecessor, Cindy Smolovick.

Slate told me he’d heard about the Texas Theatre screening series only a few days before it was scheduled to begin. He did not expect a yes from Stone on such short notice, but felt obligated to make the offer because “it’s fair to say that Oliver Stone was a direct influence on the development of the archives [in the 1990s] and the premiere collection in our archives, which is the JFK materials.”

Author