The night before Michael Isikoff came to Dallas, I got an e-mail from Barrett Brown. “Apparently Isikoff is freaked out about having another journalist here,” it said. “But I’ll secretly record the proceedings and provide to you.”

A little context: Michael Isikoff is a former investigative reporter for Newsweek. Now he’s a correspondent for NBC News. He flew in from Washington, D.C., in late February with a producer and a cameraman to talk to Brown about his involvement with a notorious international group of hackers called Anonymous that recently used their Low Orbit Ion Cannon to bring down the websites of MasterCard and Visa and the Swedish government, among others, because the institutions had made moves hostile to WikiLeaks and its founder, Julian Assange. It’s complicated—as Isikoff would learn. But more on that in a moment.

Me, I first encountered Brown in 1998, when he was a 16-year-old intern at the Met, a now-defunct alternative weekly where I worked. Brown and I had not kept in contact, but last year he returned to Dallas from New York City, we got reacquainted, and he wrote a story for this magazine. I’d been talking with him for a few weeks about his work with Anonymous, about how they’d exposed a scheme by a government cyber-security contractor to conspire with Bank of America to ruin the careers of journalists sympathetic to WikiLeaks, about how Anonymous helped the protesters in Tunisia and other Arab countries. I wasn’t about to miss out on the surreal scene of Isikoff and a television crew descending on Brown’s apartment.

I had been to Brown’s Uptown bachelor pad before. The 378-square-foot efficiency was dimly lit and ill-kept. Dirty dishes were piled high in the sink. A taxidermied bobcat lay on the kitchen counter. Brown is an inveterate smoker—Marlboro 100’s, weed, whatever is at hand—and the place smelled like it. An overflowing ashtray sat on his work table, which stood just a few feet from his bed in the apartment’s “living room.” Two green plastic patio chairs faced the desk. I left with the feeling that I needed a bath.

On the morning of Isikoff’s visit, though, I see that much has changed. Brown’s mother, having heard that company was coming, paid to have the carpet shampooed. The kitchen is now tidy. The bobcat has been hung on a wall, replaced on the kitchen counter by a bowl of fresh fruit. A lamp casts a warm glow on Brown’s work table. His 24-year-old girlfriend, a graphic designer named Nikki Loehr, sits on his bed with a laptop. She borrowed a framed Peter Saul drawing worth tens of thousands of dollars from her client, Dallas art dealer Chris Byrne, to spruce up the place. Brown, of course, would have none of it. Bobcat? Yes. Fancy artwork? Television viewers might get the wrong impression. The drawing sits in his closet.

Isikoff’s cameraman and producer are the first through the door. Then the man himself, suited, gray hair, short. We shake hands. It feels awkward.

Ever the congenial host, Brown introduces us. “Tim’s a friend,” he says to Isikoff. “He’s writing a story. You guys can have a turf war if you want, but I’m on day four of withdrawals from opiates, so I don’t want to get involved.” Only, because he speaks in a low, rapid baritonal mumble, like he is the world’s worst auctioneer, it comes out:

“Timsafriendhes‑writingastoryyouguyscanhaveaturfwarifyou

wantbutImondayfourofwithdrawalfromopiatessoIdontwanttogetinvolved.”

Having mumbled the introduction, Brown steps out onto the tiny second-floor patio to smoke a cigarette, leaving me with Loehr, Isikoff, and his two-man crew. The guys from D.C. stare at me.

“What did he just say?” the producer asks.

“Barrett said that I’m a friend of his and that he’s on day four of withdrawals from opiates.”

“Anonymous is a process more than it is a thing. I can’t speak on behalf of Anonymous, because there’s no one who can authorize me to do that.”

Barrett Brown

Brown has used heroin at various points in his life. On the night about a year ago that he met Loehr, in fact, at the Quarter Bar on McKinney Avenue, he told her he was an ex-junkie. “Ex” is a relative prefix. To manage his addiction, Brown was prescribed Suboxone, a semisynthetic opioid that is meant to be taken orally, but he had been dissolving the film strips in water and shooting the solution to produce a more satisfying high. On the Sunday before Isikoff’s visit, Brown showed me the track marks on his arm. He said he had run out of Suboxone, though, and was saving his last dose because he didn’t want to suffer through withdrawals during his big television interview. Then Isikoff rescheduled from Tuesday to Thursday. Brown couldn’t wait. Now he is hurting.

Isikoff and his crew seem to have trouble processing it all. Was Brown kidding about the drugs? Who is this friend again? And will he have to interpret everything Brown says? They are too befuddled to fight any “turf war.” In any case, Brown returns from his smoke break and launches into a primer on Anonymous, sending the cameraman scrambling to set up his lights. The producer clips mics to Brown and Isikoff. I slip into the kitchen, where I can eat the grapes that Brown’s mother bought for him while I watch the proceedings.

For the next five hours, Brown explains the concept of Anonymous (an interview session topped off with a B-roll stroll for the cameraman on the nearby Katy Trail). Several factors complicate this process. First, Brown lives under the flight path to Love Field. Southwest Airlines jets continually drown out Brown’s mumblings, forcing the producer to close the patio’s sliding glass door. The bright camera lights proceed to heat up the small room in no time. Exacerbating the stuffiness, Brown chain-smokes flamboyantly throughout the entire interview.

Second, Brown’s computer setup makes it tough to ride shotgun. His parents gave him a large Toshiba Qosmio laptop, but Brown used it to play video games before spilling Dr Pepper on the keyboard. It is out of commission. He does his work on a Sony Vaio notebook that’s so small it looks like a toy. Brown claims to have 20/16 vision, so the tiny screen doesn’t bother him, but Isikoff has to squint and lean in as Brown takes him on a tour of Internet Relay Chat rooms, or IRC, where Anonymous does much of its work. (I tag along, from my iPad in the kitchen, just a few feet away. When they enter a room where Anonymous discusses its operations in Libya, I type, “Say hi to Isikoff for me.” Isikoff: “Who’s that?” Brown, laughing: “That’s a writer I know.” As they click over to another room, I pop in again: “Isikoff is clearly a government agent.” So I don’t help, either.)

Finally, there is the inscrutable topic itself. Anonymous is sometimes referred to in the mainstream media as a group or a collective—the Christian Science Monitor went with “a shadowy circle of activists”—but Anonymous, per se, doesn’t exist. It has no hierarchy, no leadership. So even though Bloomberg and others have called Brown a spokesman for the group (which, again, isn’t a group at all), Brown denies having any position within Anonymous.

“Anonymous is a process more than it is a thing,” Brown tells Isikoff. “I can’t speak on behalf of Anonymous, because there’s no one who can authorize me to do that.”

When he explains Anonymous to a newbie, Brown relishes the inevitable confusion and will toggle between sincerity and irony to heighten it. Until you’ve spent some time with him, it’s hard to know what to believe. When you’ve gotten to know him better, it’s even harder.

“You have to remember,” Brown says, reclining in the green lawn chair, one arm slung over its back, a cigarette dangling between his fingers, “we’re the Freemasons. Only, we’ve got a sense of humor. You have to wield power with a sense of humor. Otherwise you become the FBI.” Here Brown is half-kidding.

Later, when Isikoff gets confused by the online lingo used by Anonymous, Brown says, “I think we’ve done more than Chaucer to enrich the English language. We should get a medal. Where’s the medal, Michael?” Here he is entirely kidding.

I think.

Brown first began collaborating online with Anons in 2006, though an informal organization didn’t exist at the time—much less a formal one that denies its own existence. These were just kids idling on websites such as EncyclopediaDramatica.com and the random imageboard /b/ on 4chan.org. They were interested in arcane Japanese web culture and, of course, pictures of boobs. “Everyone there was anonymous,” Brown says, intending a lowercase “a.” “It just started as a joke.”

Brown was part of what he calls “an elite team of pranksters” that did whatever they could to make people miserable on Second Life. They developed a weapon that propagated giant Marios until certain areas of the online universe crashed. They would go into a concert and produce a loud screaming that no one could stop. They went into nightclubs for furries, people who get off by wearing animal costumes, and hassled them.

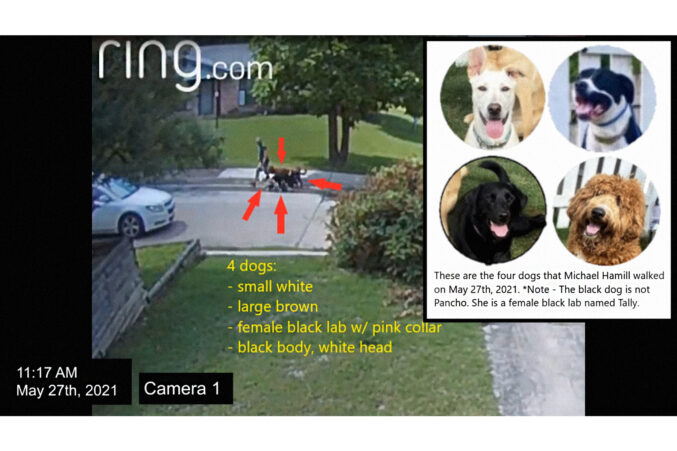

But Anonymous, with a capital “A,” didn’t coalesce into a recognizable phenomenon until 2008, when the Church of Scientology tried to remove an embarrassing YouTube video of a wild-eyed Tom Cruise talking about how awesome Scientology is. Anonymous claimed the move was censorship and, in response, published its own YouTube video. Over images of swiftly moving clouds, a computer-generated voice declared war on the church. That war, Project Chanology, continues to this day.

Anonymous’ efforts to bring down the Church of Scientology and other enemies have evolved to include all manner of tactics, both online and off, but the group’s main weapon is the Low Orbit Ion Cannon. (For clarity’s sake, I will hereinafter refer to Anonymous as a group, even though various members of the group have repeatedly stressed to me that it isn’t one.) The Low Orbit Ion Cannon, or LOIC, is a piece of software. Right now, you can download it from any number of easily accessible servers and install it on your computer. Launch it, and you just joined a botnet.

A botnet is a number of computers—could be hundreds, could be tens of thousands spread across the planet—that follow the instructions of a central command. Until Anonymous came along, botnets were generally assembled by bad guys, organizations like the Russian mafia, Chinese hackers. They build botnets on the sly, installing malware on computers that turns them into zombies without their owners’ knowledge. Each zombie can fire thousands of requests per second at a target website. So while you’re working on that cover sheet for your TPS report, your computer is part of a joint effort to overwhelm a company’s server and crash its website. That effort to crash a site is called a Distributed Denial of Service attack, or DDoS. The bad guys use DDoS attacks to extort money, but they can also use their botnets to send spam and steal people’s identities. In 2009, the antivirus software firm Symantec said it had detected nearly 7 million botnets on the internet.

Anonymous was the first group to build an operational voluntary botnet. By running the LOIC on your computer, you are, essentially, declaring your allegiance to Anonymous. You donate part of your computer’s processing power to the cause. That cause—or, if you prefer, the target—is determined by rough consensus among Anons.

If the Church of Scientology gave Anonymous its first major target the group could agree on, then Visa and MasterCard gave Anonymous its first big kill, the trophy that made the world take notice. Last year, at the urging of Senator Joe Lieberman, who heads the Senate Committee on Homeland Security, PayPal froze WikiLeaks’ account, and Amazon booted the organization off its servers. Visa and MasterCard stopped processing donations to the organization, saying in a press release that they were taking this action because WikiLeaks was engaged in illegal activity. Never mind that WikiLeaks had not even been charged with a crime. Anonymous responded with Operation Payback.

Which member of Anonymous first suggested that MasterCard should be a target of the LOIC? There’s no telling. But they discussed it in an Internet Relay Chat channel that anyone could have joined—that, in fact, anyone can still join. Anonymous uses IRC because it conceals identities and because it establishes a technical barrier to entry. Though anyone can join the conversation, only a certain type of person will. There’s software to download. There’s lingo to learn. And so on.

Sometimes Anonymous will actually conduct an online poll to determine the target of a DDoS. It’s very democratic. But the final decision about where to point the Low Orbit Ion Cannon is made by an IRC channel operator, an Anon who has the power to declare the official topic of the channel. As with the animals on Orwell’s farm, all Anonymous are equal, but some are more equal than others. It’s hard, obviously, to get a reliable estimate on the number of those elite Anons who are channel operators. Brown told me it could be a few dozen. When those—don’t call them leaders—change the topic of an IRC channel, all the LOIC-armed computers linked to that channel will automatically fire at the target. That’s when embarrassing things happen to ill-prepared companies (and governments, too).

The great thing about Anonymous’ botnet is, it never sleeps. With involuntary botnets, users turn off their zombie computers when they go to bed at night. The botnet army never fights at full strength. Anonymous’ voluntary botnet might be small, but it packs a powerful punch.

When the Anons working on Operation Payback pointed the LOIC at MasterCard’s website on December 8, 2010, it crashed in about five minutes. Visa crumbled in 30 seconds. Anonymous didn’t target the servers that process credit card transactions, just the companies’ websites. The key to the attack was the realization by Anonymous that Visa and MasterCard had left themselves vulnerable by locating all their servers in the same general area. Anonymous had discussed attacking Amazon, too, because it booted WikiLeaks off its servers, but Amazon houses its servers in data centers all over the globe. Take one down, and the traffic gets rerouted. Amazon stays online. Not so with Visa and MasterCard.

How many computers did it take to bring down the credit card giants? It’s impossible to peg a precise number. But during the four weeks when Operation Payback was at its height, Gregg Housh says the LOIC was downloaded 60,000 times. Housh is 34 and lives in the Boston area, but he was born in Bedford and lived in North Texas until he was 16. He is intimately aware of how Anonymous works but says he doesn’t participate in any of its illegal activities. In the days following the attack on MasterCard, the task of explaining all the forgoing to reporters largely fell to him. He doesn’t mind speaking to the press and using his real name because, as an organizer of Project Chanology (he and a small group of collaborators posted that first Anonymous YouTube video with the clouds), his name became public in lawsuits filed by the Church of Scientology. Too, he spent three months in federal prison in his 20s for software piracy. Authorities are already well-acquainted with him.

“Everyone just knows that Gregg is willing to talk to The Man,” Housh says. “A lot of news organizations, the New York Times, don’t want to go with anonymous sources. They have policies against it.” On December 10, two days after Operation Payback hit MasterCard, Housh did 37 interviews. “I’ll tell you, man, I work from home, so it makes it a little easier for me to do that, but it was becoming too much. And in comes the cavalry, Barrett, to take some of the load. That was nice.”

Housh met Brown online in February of last year, after Brown had written a story for the Huffington Post explaining Anonymous’ actions in Australia. The government there was attempting to ban three specific forms of internet pornography: small-breasted porn (deemed by the Australian Classification Board too similar to underage porn), female ejaculation (deemed to be a form of urination), and cartoon porn (duh). Anonymous, in response, launched Operation Titstorm, which included not only a DDoS attack that brought down the government’s main website, but a torrent of porn-related e-mails, faxes, and prank phone calls to government officials. In his HuffPo piece, Brown explained the larger context of Anonymous’ actions. After referring to William Gibson’s 1984 sci-fi novel, Neuromancer, which popularized the term “cyberspace,” Brown wrote the following in an essay titled “Anonymous, Australia, and the Inevitable Fall of the Nation-State”:

“Having taken a long interest in the subculture from which Anonymous is derived and the new communicative structures that make it possible, I am now certain that this phenomenon is among the most important and under-reported social developments to have occurred in decades, and that the development in question promises to threaten the institution of the nation-state and perhaps even someday replace it as the world’s most fundamental and relevant method of human organization.”

Bear in mind that Brown was talking about sending pictures of women with small boobs to government officials. In Australia.

“It was an interesting piece about nation-states and about their slow decline,” Housh says. “I found some of what he said to be quite outlandish and some of what he said to be quite interesting. You look at a few of these that are going on right now”—meaning Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and others—“and he might have been a little prescient.”

Housh sent Brown an e-mail saying that he liked the Huffington Post piece and that Brown seemed to understand Anonymous better than most journalists who’d written on the topic.

Brown responded: “That’s because I am Anonymous.”

A week before the Michael Isikoff interview, Barrett Brown and I are sitting on the rooftop patio at the Quarter Bar. Or, rather, I am sitting. Brown is pacing like a caged animal, chain-smoking, and drinking a Cape Cod. He likes the Quarter Bar because he doesn’t own a car and he can walk here from his apartment with his Sony Vaio notebook and get work done while he smokes and drinks. The staff knows him.

It’s a weekday, early. McKinney Avenue is beginning to flow with shiny cars headed north. We have the patio to ourselves. Brown is wearing cowboy boots and a blue pin-striped oxford sloppily tucked into blue jeans. He wears the same outfit every day. He owns a dozen identical blue pin-striped oxford shirts. He wears only boots because he hasn’t bothered to learn to tie shoelaces properly. (When Nikki Loehr told me that being Brown’s girlfriend can be exhausting because she must work to keep him on track, citing as one example of Brown’s ADD-powered absent-mindedness his inability to “tie his own shoes,” I thought she was kidding. She wasn’t.)

As Brown paces and recounts some of the highlights he’s amassed in just 29 years, it’s tempting to brand him as a fabulist. He’ll begin an anecdote with “I once had to jump out of a moving cab in Dar es Salaam.” But then he mentions that he went to Preston Hollow Elementary School with George W. Bush’s twin daughters. My mother taught the Bush twins at Preston Hollow. I tell him this, and he remembers my mother.

“I was the poet laureate of Preston Hollow!” he says. In third grade, he tells me, he used a phone in the principal’s office to order a pizza from Domino’s, which he had delivered to his classroom. He wasn’t trying to make trouble. He simply didn’t know there was a rule against ordering pizza. But his English teacher flipped, sent him to the principal’s office, where he was held in a sort of in-school suspension during which he wrote a poem about getting in trouble. “Ask your mother about me,” Brown says.

Karen Lancaster says her son developed a capacity for moral outrage at an early age. “He was furious when he was 6 and found out there was no Santa Claus,” she says.

Later that night, I call my mother, who taught him art. “Do you remember a kid named Barrett Brown from Preston Hollow?”

“Barrett Brown? Oh, my God,” she says, instantly recalling an elementary student she taught more than 20 years ago. “I don’t remember them all. But I remember him. Yes, he was the poet laureate. I don’t have it anymore, but I kept that poem for years.”

Having now had several corroborative conversations like the one with my mother, I am forced to conclude that most of what Brown says is accurate—if not believable.

He grew up comfortably in Highland Park. His father, Robert Brown, hailed from East Texas and came from a family of means. “I made a lot of money when I originally came to Dallas,” Robert says. “I eventually had $50 million in real estate holdings all across the state. But I got caught up like a lot of people did in the ’80s. I was highly leveraged, lost pretty much everything.”

Partly due to the financial strain, Brown’s parents divorced when he was 7. He and his mom shared a room in his grandmother’s house for a few months, until his mom could get on her feet. Karen Lancaster says her son developed a capacity for moral outrage at an early age. “He was furious when he was 6 and found out there was no Santa Claus,” she says. “He wasn’t mad about there not being a Santa. He was upset with me. He said, ‘You lied to me. How could you make up such a story?’”

Lancaster says her son had severe ADD and that the classroom was torture for him. But he read voraciously on his own, diving into Ayn Rand and Hunter S. Thompson while he was still in middle school.

About that time, Brown also began investigating the possibilities of online networks. This was circa 1995, before the internet as we know it today existed. Back then, bulletin board systems ruled, chat rooms with their own phone numbers for dial-up access with a modem. At 13, Brown found a BBS that changed his life. It enabled him to talk to girls. Years later, he would use the experience as grist for an essay in the New York Press.

“Early in our communication,” Brown wrote, “Tracy informed me that I could touch her breasts if I wanted to. I conveyed in turn that this would be to my satisfaction and that I would entertain other proposals of a similar nature. Over the next months, I was able to graduate to second base, to third, and finally to dry humping.”

In high school, at the Episcopal School of Dallas, Brown continued to distinguish himself. Freshman year he and a friend formed the Objectivists Club. “They began their own civil disobedience then, unbeknownst to us,” Lancaster says. “Ayn Rand was an atheist, and here he was in this Episcopal school. They decided not to sing hymns in chapel. So, of course, we got calls about that.”

The following year, he got into trouble for having sex with an ESD girl on a school trip to New York. The administration couldn’t prove that the act had occurred, though, so he was merely given in-school suspension (he passed the time by drawing comic books about World War II). That summer, in 1998, he landed the internship at the Met. In a brief “Meet the Intern” feature in the front of the paper, he was pictured wearing sunglasses. The copy read: “Barrett wears sunglasses indoors. He was a sophomore last year at the Episcopal School of Dallas, but he refuses to return next year. He has earned a reputation as a phlegmy young man for loudly clearing his throat and spitting in editors’ personal trash cans. He claims to have lost his virginity in New York, on Broadway. And last week he wrecked his mom’s Jeep Cherokee. We asked him what he’s learned here at the Met, and Barrett said, ‘How adults really act when they think kids aren’t watching.’ But Barrett’s a smart, hard-working kid, and he’ll always have our highest recommendation.”

His mother saved that clipping. She says Brown’s boast about his accomplishments in New York would have gotten him expelled if he hadn’t decided to forgo his junior year and instead travel with his father to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. It was there that Brown had to jump out of a moving cab—though because of the mumbling, it’s not clear why. Dar es Salaam was a dangerous place in the summer of 1998. In August, two car bombs exploded at the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, killing 224 people and wounding more than 5,000 others. For many Americans, it was the first time they heard the name Osama bin Laden. Brown says he saw corpses in the street.

The trip to Tanzania was supposed to be a profitable one for Robert Brown. He’s a big-game hunter, and on previous expeditions there, he’d seen vast hardwood forests that had never been harvested. He and his partners brought over $1 million worth of sawmill equipment and planned to launch an export business. But the corrupt government ruined them. With seven shipping containers loaded with equipment sitting on the docks in Dar es Salaam, Robert Brown says he simply couldn’t find the right official to bribe. As the project stalled, Barrett Brown found himself with plenty of time to conduct a dual-credit correspondence course online through Texas Tech, which allowed him to graduate high school and earn college credits. When his father’s money finally ran out, they returned to the States.

Brown moved back in with his mother and got a job at the Inwood Theatre, where he made popcorn, took tickets, cleaned the theater. He remembers one night when the father of the ESD girl to whom he’d lost his virginity came in and was none too pleased to see him. When he wasn’t working, he was reading. Or drinking whiskey with Hockaday girls who’d come over to his house after school.

Mirna Hariz was one of those girls. After Brown eventually got into UT Austin, she wound up there, too. “We all used to hang out at his house,” she says. “One day he had a test. We said, ‘Barrett, I thought you had a test right now.’ He said, ‘I’m not going.’ We said, ‘You’re going to have to make it up?’ He said, ‘No. I’m not going to school anymore.’ He never mentioned it again. That was just it.”

After he dropped out, Brown bounced among New York City, Austin, and Zihuatanejo, taking on a succession of writing jobs and freelance gigs. He got fired from Nerve.com, he says, for “intransigence.” He wrote copy for AOL—but then he stopped. In 2007, he published a book with Jon P. Alston called Flock of Dodos: Behind Modern Creationism, Intelligent Design, and the Easter Bunny. Alan Dershowitz described it as being “in the great tradition of debunkers with a sense of humor, from Thomas Paine to Mark Twain.”

By December 2009, Brown was living on Hariz’s couch in New York City. She had become a lawyer and had moved there to work on the lawsuit filed by emergency workers who were denied long-term medical coverage for ailments caused by inhaling what was left of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers. Hariz’s apartment was in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn.

“Mirna had two rules,” Brown says. “ ‘Don’t shoot up, and don’t f— girls on my bed.’ I broke both those rules pretty quickly.”

He didn’t just break the rules. Again, he bragged about it—in a fashion. For the New York Press he wrote an anonymous story about an encounter in Hariz’s apartment with a girl who asked him to pretend to rape her on their first date. An excerpt:

“The date was going well even before it started going memorably, which was bizarre, as I gave off every warning signal as to my failures as a person, like having to share a coffee mug of vodka with the girl because I’d accidentally broken all the glasses in the apartment. At some point I actually made her look at this video game I was playing, called Dwarf Fortress, in which I pretended that I was some large number of dwarves, all living together in a fortress. Eventually she relented and we had sex, which was probably for the best.”

His date wrote a companion piece, also anonymously, in which she said, “There was something appealingly wholesome about him, so all-American—he was cowboy boots, medium-rare bacon cheeseburgers, and Monday Night Football—that I just couldn’t resist.”

Not every day in Williamsburg was so debauched. Hariz remembers coming home once to find Brown playing basketball with what she calls “street toughs.” “There was the one skinny white guy playing with all these huge black guys,” she says. “He leads this very Kerouac-seeming life. When he goes out, it’s for adventure.”

But Brown wasn’t going out much. By this point, he’d become deeply involved with Anonymous’ efforts to support WikiLeaks, spending marathon sessions hunched over his computer.

“I would try to get him to come out with me, go to a bar, but he wouldn’t,” Hariz says. Instead, Brown would stay home and shoot heroin. “When he’s messed up, all he does is work. It’s not like he’s out there, partying it up, engaging in risky behavior. He’s just working—while doing drugs. I’d get up, and he’d be sitting in front of his computer, with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. When I’d get home, he’d be sitting in the same position, working. I’d go to bed at 4 in the morning, wake up, and he’d still be there.”

This is when Brown wrote the Huffington Post article about Operation Titstorm and wound up admitting to Gregg Housh that he, too, was Anonymous. But Brown didn’t come out publicly until just a few months ago, after the Operation Payback DDoS attacks on Visa and MasterCard and others. Dutch authorities quickly arrested a 16-year-old boy in The Hague, Netherlands, identifying him only as Jeroenz0r, an IRC operator (aka one of the Anons that determines a target for the Low Orbit Ion Cannon). Anonymous decided that it had to get its message out quickly—the message being that MasterCard, according to Anonymous, was processing payments to the Ku Klux Klan but not to WikiLeaks, which Anonymous considers not just a kindred spirit but a legitimate journalistic enterprise. In fact, Housh has said that Anonymous launches DDoS attacks in some cases with the sole aim of spurring the press to ask questions, thereby giving Anonymous a forum in which to discuss its agenda.

With Operation Payback, Anonymous had created a huge forum. Yet it had only one real spokesman to take advantage of the opportunity, poor Gregg Housh, who was, let’s not forget, trying to get some actual bills-paying work done at home when the media came calling.

Enter Barrett Brown, former poet laureate of Preston Hollow.

The promotion to unofficial spokesman for a nonentity might seem like a swell thing for Brown, something he could write home about, tell his parents to stop worrying. There are drawbacks, though.

First, and most obvious, the nonposition comes with a nonsalary. Also no health benefits nor 401(k).

Second, he’s now what Anons call a namefag. The term is not intrinsically derogatory. It just means that one has publicly identified oneself as Anonymous, using the name on one’s birth certificate. I’ve talked to Anons on IRC who are quite happy with the work Housh and Brown have done to explain Anonymous to the media and, in Brown’s case, write about the group and organize legal defense for members who have been raided. One Anonymous hacker told me that Housh and Brown “are strong observers only, giving them the right to identities.” But then there are those who detest namefags.

“It isn’t cool at all being this person,” Housh says. “About 75 percent of the people involved in things are happy someone is trying to keep the media straight. Fifteen percent don’t give a shit either way and just shrug people like me off as namefags and media whores. The other 10 percent spend time every day trying to make your life hell, attacking you, telling everyone lies about you.”

Housh says disgruntled Anons have handed over fake chat logs to the FBI purporting to show that he runs Anonymous. Anons have dropped dox on Brown, too, published his personal information in an effort to discredit and embarrass him.

And it’s not just the lack of anonymity that riles up that 10 percent of Anonymous. Brown believes that Anonymous is a force for good, that it can and should be used to topple oppressive regimes, eradicate the necessarily corrupt nation-state. Brown has been at the vanguard of Anonymous’ operations in Tunisia and other Arab nations, writing guides to street fighting and first aid that Anonymous posted on government websites it had taken control of. Much was made about how well-organized the Egyptian protestors were because they could coordinate their efforts on Facebook. Partly that’s thanks to Anonymous Facebook spammers that mass-invited thousands of Egyptians into the protest groups.

This sort of work gets an Anon branded as a moralfag. I spoke online with the user who runs the Twitter account @FakeGreggHoush. The user said the real Gregg Housh would identify her as a woman named Jennifer Emrick, but the user identified himself as Donald Wassalanya, a name that I could not find in public records. The real Housh said the user could be Emrick—or someone else. Other Anons on IRC told me Emrick was Fake Housh. In any case, Fake Housh seems to speak for that 10 percent.

“Gregg would have ya live in a world where Anon is a force for good, something that can be marketed,” Fake Housh says. “We do what we do because we can, and it amuses us, not because it’s just or right. Morals have their place in our society. Anonymous isn’t a place for morals.”

Fake Housh says that what Brown has been doing in Libya and elsewhere is “armchair protesting” that has little if any effect on the protests. “It’s just a way to look good and feel good.”

Finally, there is a third drawback to Brown’s new, more visible role in Anonymous. He just might get arrested. Because Brown likes to brag. Just like he did with the poem at Preston Hollow and the “Meet the Intern” ditty about the eventful school trip to New York City and the New York Press essay about the rather flagrant violation of Mirna Hariz’s second rule, Brown, now that he’s a namefag, has taken to calling enemies of Anonymous and certain federal authorities (sometimes one and the same) to tell them how cool he is. Of course, that’s not what he explicitly says. He says he’s calling to help.

A few weeks ago, he talked to a woman in the NSA. He says he contacted her as a courtesy, to let them know that Anonymous had a copy of Stuxnet. That would be the most infamous, most complex bit of malware ever written, the world’s first weaponized computer virus, which was revealed last year to have crippled much of Iran’s nuclear program. Some think the Israeli government created it, possibly with help from the United States. The copy Anonymous has—meaning, also, that Brown has a copy of Stuxnet on his harmless-looking Sony Vaio notebook—is defanged, to an extent.

But still. Stuxnet. At the Quarter Bar.

And how, you may well wonder, did both Anonymous and the namefag who bores his sexually adventuresome dates with Dwarf Fortress come to own a copy of Stuxnet? First the slightly technical explanation of Anonymous’ greatest stunt yet, then the way Stephen Colbert described it.

On February 4, days after authorities had raided some 40 suspected members of Anonymous in connection with Operation Payback, Aaron Barr, the CEO of California-based cyber-security firm and government contractor HBGary Federal, stepped up and asked to be a target. Barr gave an interview to the Financial Times in which he claimed to have identified Anonymous’ leadership using social engineering hacks—essentially trolling Facebook and other networks. Barr told the Financial Times he planned to unveil his research at an upcoming security conference.

Brown says Barr had everything wrong. He was about to release names of innocent people whom the feds would then raid. Nonetheless, Anonymous issued a press release, partially written by Brown, conceding defeat.

Then, the very next day, they attacked. Using something called an SQL injection, they broke into the database underlying hbgaryfederal.com. There, Anonymous hackers found what Brown later described in an article for the Guardian as a “farrago of embarrassments”: a carelessly constructed database, systems running software with known security flaws, passwords poorly encoded, and, worst of all, the same password used on multiple systems.

Within hours, Anonymous had destroyed HBGary Federal and its parent company, HBGary.

On February 24, Colbert did a lengthy segment on the hack, which by then had become international news. Here’s how he played it:

“Barr threatened Anonymous by telling the Financial Times he had collected information on their core leaders, including many of their real names. Now, to put that in hacker terms: Anonymous is a hornet’s nest. And Barr said, ‘I’m going to stick my penis in that thing.’”

Colbert relayed that Anonymous took down Barr’s website, stole his e-mails, deleted many gigabytes of HBGary research data, trashed Barr’s Twitter account, and remotely wiped his iPad. “And he had just reached the Ham ’Em High level on Angry Birds,” Colbert said, to much studio laughter. “Anonymous then published all of Barr’s e-mails—including one from his wife saying, ‘I will file for divorce’—and Barr’s World of Warcraft name, sevrynsten. That’s right. They ruined both his lives.”

Four days after the Colbert jokes, Barr resigned his post at HBGary Federal.

Of course, Brown had called Barr an hour after the hack. He played a recording of that conversation for me. He keeps recordings like these as trophies. As the conversation grows less productive, somewhere around the 10-minute mark, Brown deadpans: “Well, you’ll have a lot to talk about at the security conference.” (HBGary later decided to withdraw from the conference.)

“Our people break laws, yes. When we do so, we do it as an act of civil disobedience. We do it ethically.”

Barrett Brown

The HBGary hack would amount to nothing but lulz—laughs at someone else’s expense, the only acceptable motivation for any Anon who isn’t one of those moralfags—except that’s how Anonymous got its copy of Stuxnet. Someone at the antivirus firm McAfee had e-mailed it to Barr. But, far more important, buried in the 70,000 HBGary e-mails (which Anonymous made available to everyone on the file-sharing service BitTorrent) was clear evidence of a far-ranging conspiracy among several powerful corporate entities to commit what could be crimes. HBGary Federal, along with two other security firms with federal contracts, Berico Technologies and Palantir Technologies, were crafting a lucrative sales pitch to conduct a “disinformation campaign” against critics of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Hunton & Williams, the well-connected Washington, D.C., law and lobbying firm that was soliciting the work, also counts as a client Bank of America. The hacked e-mails show that the three security firms were working on a similar proposal to target supporters of WikiLeaks on behalf of Bank of America, which has reason to believe it might be the group’s next target.

As February drew to a close and D Magazine went to press, about a dozen House Democrats called for an investigation into Hunton & Williams and the three security firms, saying that the hacked e-mails appear “to reveal a conspiracy to use subversive techniques to target Chamber critics,” including “possible illegal actions against citizens engaged in free speech.”

And so it comes to pass that the kid who first used his computer to feel a girl up, then later found he could use it to mess with furries, now finds himself using it to fight for free speech, of all things.

“Our people break laws, yes,” Brown says. “When we do so, we do it as an act of civil disobedience. We do it ethically.”

But everyone who’s Anonymous is anonymous. So there are probably some bad people helping out. Bad people acting ethically?

“We don’t do background checks on people,” Brown says. “There are bad Anons, sure. They could be doing corporate evil or regular evil. But while they’re with us, they’re doing good.”

At one point, he tells me that he’s trying “to show these kids that being bad isn’t awesome.” He’s mostly joking.

Maybe.

On the Sunday afternoon before Michael Isikoff’s visit to Dallas, Barrett Brown and I are having brunch on the patio of the Old Monk, on Henderson Avenue. Or, rather, I am having brunch. Brown orders only coffee and orange juice. He is polite to the waitress, saying “please” and “thank you” each time she fills his mug. He’s smoking and wearing the boots-and-blue-oxford uniform. The weather is perfect.

We come around to the topic of the future and what it holds for him. It’s not something he likes to discuss. He says he doesn’t like to make plans. “Hitler had plans,” he says.

We talk about his prospects of earning a real living. Money hasn’t held much sway over him. Having watched his father lose so much of it, he sees it as ephemeral. But he’s working on a film treatment for a producer in Los Angeles. He’s got another book coming out soon.

I tell him that the drugs and the constant smoking give me concern. I can’t help myself. In some ways, I still see him as that phlegmy 16-year-old intern who could use some good advice. I tell him something Loehr told me, that if he’s going to have an impact, he’s going to have to connect with people, and he can’t do that on heroin. Words to that effect.

“At the risk of sounding like an asshole,” he says, “a lot of the rules don’t apply to me. My heroin addiction is much different than everyone else’s.”

Then he gets serious. Sort of. “Everything I’m doing now is healthier than it was,” he says. “I used to roll my own cigarettes. Now they have filters. I’m doing all this gay shit. I’m jogging on the Katy Trail. I’m dating a girl. How gay is that?”

Author