Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

“Help me, I can’t say the light I need to travel by”

–Judith McPheron (1946-1981)

Discovery: Oklahoma City, Spring 1976

While bending down to light the gas in the fireplace, Judith McPheron feels a lump behind her right knee. The doctor tells her it is a Baker’s cyst and that it has to come out.

“Yep, that’s a beauty,” says the doctor, looking at her legs. “You must be quite athletic. What sports do you play?”

“Athletic? I was always the last one left when the volleyball team captains chose sides.”

“Well, you must get around a lot or something. Here’s the name of a surgeon. I think you’ll like him, okay?”

The surgeon, too, wonders what sports Judith plays. The cyst is the biggest he has ever seen, he says. It doesn’t hurt when he prods with his fingers. Fun to take it out, he pronounces.

Judith and her husband travel to St. Anthony’s hospital for the surgery in June. The nurse’s aides elbow one another at the sight of Judith’s stack of books.

“It looks like we got a perfessah here,” one of them says.

She sits down on the bed, overcome by the smell. A man walks by on the roof of the next building outside. She tries to concentrate on the theory of surplus value, but the words dissolve into hieroglyphs.

They take her down to the basement and roll her around on the X-ray table, trying to get a good shot of her cyst. They draw purple lines around it and inject it, but the cyst, it seems, is unphotogenic. When the surgeon lopes in, she starts to cry.

“What’s wrong? Are they hurting you?”

“No, it’s just institutional alienation,” she says.

“Well, that’s the damnedest cyst. Won’t light up. Might be a fatty tumor. Benign of course. I’m sure you’ve thought of that.”

“No, I hadn’t.”

When Judith wakes up the next afternoon, the leg is huge and white in its plaster cast. A nurse’s aide is standing at the foot of her bed telling her that she feels bad.

“Go home, then,” Judith says, and falls asleep.

When she awakes again, her husband is there. The “cyst” is a malignant tumor. At worst, it would be off with the leg, but probably just cutting away more of the tissue where the tumor had been is all that will be needed.

“Okay,” she says. “I’ll stump around like Captain Ahab and disturb all the people reading in the library. Will you buy me a hand-carved wooden leg?”

Groggy from the anesthetic, she falls asleep again. Screaming awakens her. She clamps her hands over her mouth in case it is her own screaming, but it is not. She wishes she could get up. Look what they can do to you if you weaken, she thinks. If you let them. The stern voices of nurses come from the hallway. Suffering turns the nurses’ voices gritty with hatred and disgust. The screaming dies down to a little-girl whimper.

Later that morning the surgeon lopes in again.

“Are you a librarian?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, it’s a malignant tumor.”

“Aren’t you supposed to hold my hand, or something? How malignant?”

“I don’t know. The lab will know more tomorrow, but you’ll need more surgery.”

“Chop off the leg?”

“Maybe not, maybe so.”

“Can I go back to work?”

“Sure. Now, listen, I’m sure it hasn’t spread.”

“How are you sure?”

“Well, that’s fair. I don’t blame you if you don’t trust me. I said before that I was sure it was just a fatty tumor. But this kind, well, it moves very slowly. You’ll be fine.”

“Mind telling me the name?”

“Liposarcoma. Can I do anything for you?”

“Get me out of here.”

“Sure, just want a chest X-ray first. Just relax. I’ll get you some tranquilizers.”

Judith feels her stomach closing like a drawbridge. They take her to the X-ray room in a wheelchair. By the time the fourth person asks how she has broken her leg, she has an answer.

“Ice skating,” she says.

Wearing her only skirt over the cast, Judith receives her friends from the library at home. They bring her food, wine, and snapdragons. She laughs and talks and pretends she is royalty, while pushing the terror down.

The cast is so big she can barely get it into the bathroom. To pee she has to prop the leg up on the garbage pail, but still she wets herself and the floor. She decides to stop drinking coffee.

As long as she is not alone, she thinks, nothing can happen to her.

She wakes up on the couch, groggy, the leg hurting, and calls for her husband. No answer. She calls louder.

She drags herself, step by small step, to the back door. The car is gone. She is soaking with sweat. She drags herself back to the bed and sobs.

A minute later her husband is running through the back doorway, apologizing, crying, smoothing her skirt. He had thought she would sleep on, and he had gone to the hospital for some medical records.

She makes him promise never to leave her alone again, and laughs at herself for not being brave.

The doctor tells Judith she has half a chance. The survival rate from liposarcoma after five years is 50 percent. The doctor tells Judith’s husband that he has never seen anyone take it like she has. He thinks she must have one hell of a strong personality. Her husband tells her she is inordinately proud and mad at herself at the same time. Judith wonders why she should be studying to be a prizefighter of the psyche. It just lets the doctor off easy.

Liposarcoma, she later discovers in her research at the library, is one of the rarest forms of cancer. Less than 2 percent of malignant tumors are in the soft tissues, and only a small percentage of those are liposarcomas. They can occur in any part of the body where there is fatty tissue, which means just about anywhere. This cancer strikes at any age, but most often between 40 and 60. Judith is 30 years old.

She is sunny, chirpy, resolutely normal. Her friends’ relief at this is almost physical. She tells her brother that if he is going to act weepy, he’ll have to stand in the backyard and sing “Cherry-Ripe” with his hands on his head. Somewhere, something is resolutely hiding that will split everything apart, she thinks, as she smiles.

She has been writing poetry, and the first of six poems on cancer emerges:

Is cancer a

violent revolution or

the ebbing of the tide

I wonder as I stare

at the acoustical-tiled ceiling

trying to erase

the insistent pattern there.

Blood or salty water

it’s all the same

to me

my bones reply.

They drive to New Mexico, where Judith’s father-in-law, a radiologist, has brought in a specialist friend from Houston. They fill the little car with books and papers and create a platform in the front on which Judith can rest the cast. They stay off the interstate and drive through the bright Texas sun. Judith’s husband ticks off the names of wildflowers as they pass. In Lubbock they see a perfect double rainbow in a slate gray sky. It is an omen, they say, a good omen.

In the night, ghosts visit Judith in her sleep, asking her age, asking what terrible sin she has committed to deserve such a punishment. Her father-in-law hears her groaning in her sleep.

He is relieved that she is in good spirits. That night he tells her that liposarcoma is a very rare disease, and no one knows much about it. No one, she notices, uses the word cancer.

Out of this avoidance, another cancer poem comes:

To name a lump

is to distinguish

something we wish

were still nothing

to give it shape

and almost

the status

of a piercing organ.

(Who, really, eats

liver without wincing?)

I relinquish control

but do not want

to stop knowing

the names of things.

And it is curious,

yes, like words

we can’t imagine

once they grace

the formerly empty

piece of paper

that something grows

from nothing.

After her cast is removed, Judith is taken to another doctor. He is facing the wall when she enters the room. He turns and greets her as Mrs. McPheron. Judith notices he is 6 inches shorter than she is. He wants to know if she realizes why she is there.

“To swim the English Channel?”

The doctor suggests that perhaps she doesn’t understand the gravity of the situation.

“Well, yes, I do. I’m the gravity. I manufacture my own.”

He is annoyed and confused and doesn’t know what to say. Judith decides she is in enemy territory.

“Well,” he says, “Friday I will cut a section out of your leg, and Dr. Collins will implant radioactive gold seeds, and you’ll have another cast, and then we’ll see. Where’s your husband? What does he do for a living?”

“I’m a librarian.”

“Oh. Read a lot of books?”

“Yeah.”

“Go home, and wash with this soap every hour. This is the easy part, you know.”

“Oh. What’s the hard part?”

“Waiting. Want a tranquilizer?”

Judith rides back to her father-in-law’s house in the fine desert air, sorting things out.

Liposarcoma is a rare form of cancer. It strikes at any age, but most often people between 40 and 60. Judith is 30 years old.

She thinks of the medical shows that were popular on television when she was in junior high school. It seemed that 20 minutes of an hour-long program would be taken showing the doctors and relatives agonizing about whether to tell the patient he or she had cancer. All the factors were considered, and added up slowly, like the counting of a bridge hand.

They must have been taking payola from the American Medical Association, she thinks. Off the air, doctors are so casual and matter-of-fact that she is forced to create a counter-theory. Since no one, especially the good-guy doctors, could be so callous, they are really acting gruff to hold in their torrential feelings, which would drown them if given a chance. It is the Puritan demeanor with a vengeance. Since anyone who shows his feelings is crude and probably an emotional fake, then those who show nothing are the genuine, but dignified, emoters. This leaves no room for the truth.

The desert air is like raw silk. Between washings of her leg, Judith fussily bunches her papers together. Doves coo in the backyard. Her husband brings her a blue cowboy shirt for her return from the hospital. Presents are a kind of insurance to him, she thinks. A grandfather clock rings every 15 minutes until it is time for her trip to the hospital. She dreads it. She thinks it is like prison.

She makes a list of things she is afraid of: Being in the clutches of people who would want to lock her up in the loony bin if she acted normal. Acting normal. Getting stuck on a bedpan for an hour. Her job dissolving and floating away while she is gone. Dissolving and leaving a ring around the tub as she goes down the drain.

From her hospital window Judith can see yucca, mesquite, creosote and crown of thorns. She has no complaints about the vegetation. People peek in to see her, squeeze and poke her. She concentrates on her breathing and counts the tiles in the ceiling. Her father-in-law comes in with the Houston specialist, who sports a waxed mustache. He tells her twice how lucky she is to have virtually an entire hospital at her disposal. Judith wants to tell him that her grandfather was a socialist, but stops herself.

“Yes,” she says, “and I will soon have the most valuable leg in the Permian Basin.”

She has the room to herself because of the radiation she will emit. She will contaminate those who come near her, especially women of childbearing age, if they stay too long.

“Why,” she wants to know, “won’t I contaminate myself, then?”

She makes up a melody for Dylan Thomas’ poem, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” and sings it aloud: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” She brings it down to a whisper when she hears someone coming down the hall.

The next morning the anesthesiologist comes in early to prepare her for the surgery. He is a New York Jew, like Judith, and she is flooded with a secret comfort. She represses an urge to wink at him. Her husband comes in and lays out a hand of solitaire on her blanket, asking the cards, it seems to Judith, for an answer. The surgeon comes by and tells her she will be able to do anything she wants after the operation except play tennis.

“Fine,” she says, “I’ll give my racket to the Salvation Army.”

No one laughs. Judith feels guilty for not being athletic and promises herself she will take up running, or at least serious walking, if she gets out of this okay.

After giving her a shot, they wheel her away to the operating room with side rails up. They cannot keep her from floating. She watches everyone dancing around in the operating room for as long as she can. No one says a word to her. Why should the actors talk to the props? she thinks before going completely under.

A gray blob comes up to her cheek, touches it. She is gray. A voice tells her to wake up. She struggles to open her nostrils, her eyelids. She is singing a chain-gang song.

Never been to Houston, boys,

but I been told

women in Houston

got that sweet jellyroll.

Raise ’em up higher, higher,

drop on down,

raise ’em up higher, higher,

drop on down.

Someone is massaging her toes, a young Chicano; Judith can tell through her hands she is not in a hurry.

“Hey Ladybug, how you feel?”

“Glub, glub,” says Judith.

Judith giggles, thinking of the man in Oklahoma who had gold football emblems fitted into his front teeth. She tries to point to her teeth, giggling, but her hand seems glued down. None of this seems to make the nurse nervous. She sees her leg, white and huge again, with a plastic sack of blood sitting near it. A pudding? she thinks.

She talks to the nurse, Carolyn, and finds out about her four children, how one of her daughters wants to be a doctor. Carolyn loves her work. Judith struggles to find her father-in-law’s phone number, written on a matchbook. She gets excited, wondering where her husband is, and tries to calm herself. She picks up the receiver and asks it how she will ever call her husband. Her eyes won’t focus. Carolyn finds the number and calls him for her.

“Where are you?” she shouts. “Where? You’re abandoning me.”

“Don’t you remember?” he asks. “I was there all afternoon.”

She remembers nothing.

He comes and stands in the doorway because he has had his limit of her radiation that day. He smiles and caresses her with his eyes. Nurses want to know if they can get her anything for the pain. A sledgehammer? Judith thinks. She wants to know why she feels so funny, and her husband says it’s because they have given her a shot of something to bring her out of the anesthesia.

He leaves, and Carolyn asks her if she wants to pee. Judith loves her for not saying urinate or eliminate or empty your bladder. At night someone gives her a sleeping pill, and she wants to say she doesn’t think she’ll need it, but she can only cluck her tongue.

Later that night she looks up to see her husband sitting very straight. He talks about Melville and Ahab, and they argue about the metaphysics of missing legs.

“I cannot deceive you now,” she says. “All the ships in Christendom and some beyond will never quell that whale.”

His answers are serious, discreet, always on the side of moody Ishmael, the gazer from the mast, the man who escaped Ahab’s mad quest.

She asks what he is doing there again, so near, and he turns into the IV stand. She is devastated by the self-deception. A nurse comes in.

“Another shot? You want another shot for pain?”

There’s no shot for this. All night long she glides in and out of conversation with him.

Tarantulas crawl down the walls, and she counts the hairs on their legs. The tiles fall from the ceiling one by one, and the ceiling draws closer and closer to the bed. It will all go away, she thinks, if I can hold out for the light.

Judith stares at the bouillon on her tray and shouts silently at it: “But I am only 30 years old!”

Her leg throbs, and she still cannot focus her eyes. Terrified that something is wrong with them, she buzzes for a doctor. A guy she has never seen before strolls in wearing Bermuda shorts and knee socks. He stuffs another pillow under her leg and pokes the sack of blood.

“Nurse, empty this.”

“Well?” Judith asks.

“You rest. I’m gonna go play golf.”

Who knows, she thinks, if you complain they might gouge your eyes out and keep them on a chain in their pockets, a sort of good-luck charm. She hates herself for being so afraid.

Carolyn leaves for another floor.

“Bye, Ladybug. I’m off to the babies.”

Judith tries to hide her disappointment. In three days Carolyn has become her mother — better than a mother. Judith resolves to learn Spanish and fly away with Carolyn to the babies.

She tries to figure out the nurses. They snap like rubber bands when the doctors come by.

Only the ones at the top and bottom of the hierarchy can afford to relax. Those starched caps ain’t just for looks.

Her husband and brother-in-law come for a visit. There is only one chair, so she invites them to sit on the bed, but they are afraid they will hurt the leg. Or it will hurt them, she thinks. She keeps asking when she can go home. Soon, in a few days, they say.

A kid comes around with a fancy machine to teach her how to breathe properly. She didn’t know she needed lessons. She is offended and bored. She still can’t focus her eyes well enough to read more than a few sentences at a time.

But she has gathered some facts about her surgery. One of the doctors has said it was a beautiful incision. Her hallucinations and eye trouble have come from a clash of two kinds of anesthetics. The tissue, muscle, bone and other guck they took from her leg was clean. She wonders whether they had to chop it out. She will need crutches. Her arms feel useless. They tell her to eat red meat, but she gags at the thought of a dead animal making its way down her throat.

The day she is to leave the hospital, Judith sits in her chair, trying to pull her skirt over her head, telling herself over and over again: This is not happening to someone else. She tries to get the skirt down around her hips without getting up but it resists, a live and willful creature. She checks her watch every five minutes and wets her thumb to smooth her eyebrows.

She awakes on her father-in-law’s green couch, sweating, disoriented and full of guilt. She should not be lounging around in full view, advertising her illness, she thinks, but stiff behind white sheets and closed doors. It seems to take half a lifetime to maneuver with the crutches to the bedroom.

It is hard in a world of healthy, white-teethed, smiling, smooth-cheeked, gentile giants, she thinks. I do not care to be cared for by such glittering competence and well-being. She wishes she were an avenging angel. Then she would avenge herself.

Her brother-in-law makes red enchiladas for dinner. Like Judith, he has a passion for northern New Mexico. The red enchiladas are an apprenticeship in loving the region, a sort of ceremony.

I am glad to have a nose to smell with, a tongue to taste with, she thinks. I am happy that all the world is not washed clean and deserted every night.

The Houston specialist has phoned and said she requires no more radiation treatment. Her friends at work have sent her a new fountain pen with a gold point. She ought to write the Houston doctor a thank-you note with it, she thinks; it’s expected.

She brandishes the new pen like a sword. With this she will fight off the encroaching barbarism. With this she will write the poems of her life, and if need be, the poems of her death.

Change: Dallas, Summer 1977

Judith flies to Dallas to interview for a librarian’s job in the humanities division of the public library. She has borrowed a conventional dress for the interview. Her experience in public libraries and her credentials — BA and MA in English, MA in library science — make her a likely choice for the job.

She is determined to get it. She has a clean bill of health from a doctor, a strong love of books (especially contemporary poetry) and wants to change her life.

She is leaving her husband.

They have moved to Cincinnati, where he has a library job. Judith has none. She has tried to manufacture greeting-card verses, but sells only a few. Her mind isn’t formulaic enough. Then she finds a lump in the fatty part of her chin. A surgeon removes it, and pathologists say it is malignant. The doctors are pessimistic. Her husband begins giving her up in his mind. A poem, “Husband,” grows out of this:

Each morning, outside the east

windows, the birds squawk furiously,

recalling me to my life, willing

to sell my secrets for a nickel

to the first person who asks.

Is that what you call the abstract

prerogative? I have

a small lump in my throat

right now.

You think it’s another story,

but I know better.

Our telephone lines connect

in black and buzz

all along my lit-up veins.

I whisper tender things

at the mouthpiece, and

fish swim out your end,

glittering their fins

for all they’re worth.

Boundaries, ah, if only

you’d asked, were never

my intention.

The boundary he cannot deal with, Judith thinks, is that she is going to die and he must live.

He is faithful, he is devoted, he is considerate, but that is not enough for Judith.

One day he comes home and finds her sitting on the couch, crying. He puts his hands over his ears and walks out of the room. She cannot see his pain, for what is his pain compared to her terror?

Then the pathologist changes his mind. The tumor is not a liposarcoma but a lipoma. The two are easily confused. The lump was benign. The doctor expects Judith to be delighted, but she is furious. He can’t understand why. Her husband has yet another adjustment to make.

Suddenly she has been given back to him after he has given her up for dead.

The tension is too much for Judith. She finds an ad in a library publication and applies for the job in Dallas. The doctors send a letter to the library about Judith’s cancer surgery and the benign growth removed from her chin. Her health is good. She joins the downtown staff of the Dallas Public Library and is immediately assigned to selecting poetry and literary criticism. She sets about building the library’s collection of contemporary poetry into one of the best in the Southwest, better than that of many college libraries.

Within months after leaving her husband, Judith is divorced, and her husband remarries.

As soon as she starts work, she shows up in trousers and bright sport shirts, gypsy skirts and hoop earrings, Indian jewelry from her student days in New Mexico, striped knee socks. She stays with another librarian for a week while she looks for an apartment and finally finds one in East Dallas. She is almost ghost-like when she stays with the other woman, so careful is she to avoid disturbing her household.

She begins to make friends. The first she finds is her boss, Frances Bell, the head of the humanities division of the library. She is older than Judith, shyer, sweet-faced, deeply intelligent. Judith decides Frances is a frustrated artist, and plunges her into frank and strong friendship.

She finds Kirby Metcalfe, the library’s artist and exhibit designer, also poet, ceramist, modeler, and self-confessed self-promoter. Kirby is short, rotund, with a carefully trimmed gray beard and a round, jolly face. Sometimes he wears wide red suspenders. Judith knows a fellow spirit. One day she comes up to him and says: “I’d like to be your friend. My name is Judith. What’s yours?”

And there is June, the organizer. She’s the mother of three grown children and a teenager. After her full-time job at the library, she reads proof for local editors, who call her “Mom” Leftwich. Once June makes a decision, she acts.

Nina Israel, eight years younger than Judith, grew up in the same middle-class neighborhood on Long Island as Judith. She is girlish, sisterly, a little insecure. She is someone to giggle with. Judith gives her confidence in herself, because Judith expects it.

Sandra Halliday, of the fine-arts division, is methodical, quiet. Judith picks her out, too. Months after they have known each other, Judith and Sandy are looking at photographs of friends from the library when she comes to one of Sandy, and says to her:

“You know, I tried to get to know her, but it wasn’t easy.”

Judith doesn’t seem simply to make friends, but has a policy of making them. She singles them out, focuses her attention on them, finds out about them, and insists they respond. For some, she is too intense. They back away.

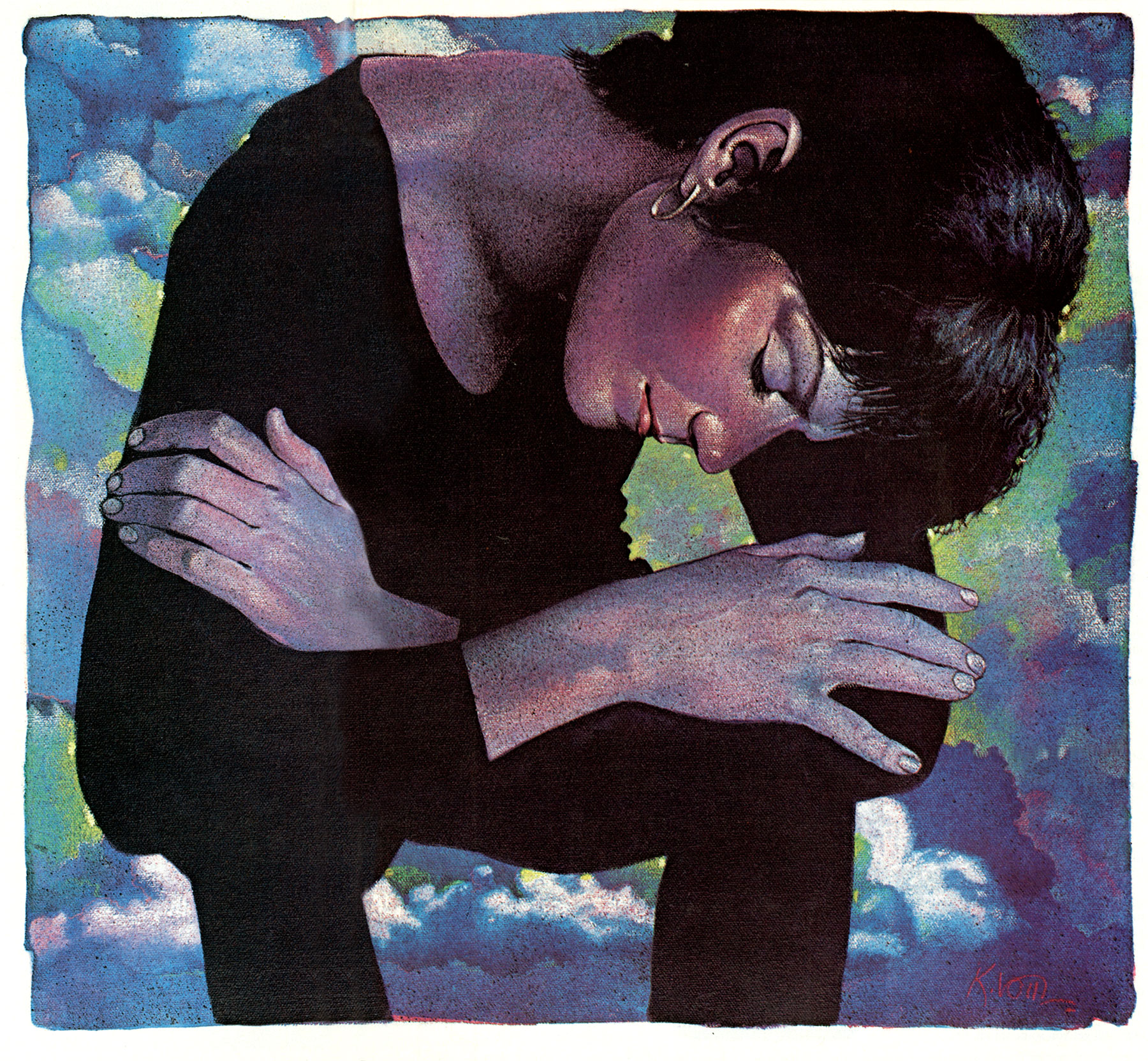

Judith, bright and cheerful, slim and young and beautiful with her large hazel eyes, strong cheekbones, wide laughing mouth and her confident way brings a spirit of levity to the humanities division. She masterminds parties. The humanities division becomes a livelier, more cohesive place.

She writes a note to a friend of Frances’ who refuses to get medical treatment for an injured foot:

Dear Drew,

The subject is hurt feet. If I were a hurt foot and my employer refused to recognize my pain, I would go on strike. I would organize the other feet, hurt or not, and shout, “Walkers of the world, unite.” I might even incite a riot or stampede. And I certainly would get someone to look at me, and find someone to tell about the cruel and unusual punishment I was receiving at the hands of my boss. I would not like very much being twice my usual size; nor would I want the rainbow hues anywhere but in the sky. What I would want is a gentle bath, some foot-wise attention, and a bit of good advice. About how to get myself back on the ground, etc. In good faith, I must warn you that as a potential employer, you may have your walkers organized out from under you, so take care.

Judith

Judith is a socialist in sentiment, if not in practice, and the following spring, she asks the librarians to think about having a May Day party. The party is never held, for Judith is gone from work that day. She is in the hospital having lumps removed from her abdomen and leg. Two others have turned up in her lungs. They are liposarcomas.

Judith distrusts doctors and hospitals by this time, hates their coldness, hates their lack of humor, hates their lack of compassion. But she finds a cancer specialist she likes, Robert Weisberg, a New York Jew, a guy who can take her needles and wisecracks and give them back. Weisberg usually wears jeans, a silver bracelet. He’s bearded, dark and nearly Judith’s age. He’s also tough and thorough. He believes in a thorough treatment of cancer with no letup just because the patient might feel a little better. He doesn’t like postponements; he doesn’t like skipped treatments.

He can’t offer Judith much. Radiation doesn’t seem to affect liposarcomas. Chemotherapy succeeds in less than a quarter of the cases, but the effects of chemotherapy on the tumors can be detected within two months after beginning treatment.

They begin immediately with chemotherapy, five afternoons a week every fourth week. The drugs are adriamycin, cytoxan, vincristine and DTIC. The adriamycin can damage the heart if taken too long. The other drugs can affect the blood. Part of the procedure of chemotherapy is to monitor the heart carefully and take monthly blood tests.

Part of the procedure for Judith is to mobilize her friends to help her through the chemotherapy. They are frightened, but they plunge ahead. June organizes a schedule and sticks it to her refrigerator door. The first day of the five days is the roughest. Someone takes her to the doctor’s office on Harry Hines Boulevard where Judith reclines on a high table covered with leatherette. The nurse tanks two bottles, a red one with the adriamycin and a clear one, connected to a y-tube, and sticks the needle in Judith’s arm. She must wait for an hour and a half or two hours while the chemicals drip into her vein.

Forewarned of the nausea of chemotherapy, Judith brings her own plastic bait bucket and plops it on a nurse’s desk. She has a favorite treatment room of the four in Weisberg’s office. From there she can see the nurses’ telephone and she can give a cute doctor there the eye. The nurses laugh and watch him come by to make a phone call from their phone just so Judith can get a look at him.

Going home is not so good. Mondays she throws up in the bait bucket while Frances drives. Unable to eat, Judith lies down and heaves. When the worst is over, Frances cooks something frozen for herself and spends the night with her. Whoever is assigned to drive her talks to her, to keep her mind off the nausea. Once in a while she tries smoking a joint, but it doesn’t seem to help. By Wednesday, it is a little easier. Wednesday she goes to June’s house. She gets into her nightgown and lies down at one end of a long couch, with June’s black Labrador retriever, Othello, at the other end. Judith refuses to own a television herself, but on Wednesday nights, she watches television with Robbie and Genie, June’s daughters.

“I love this guy Starsky,” she says.

She can eat a little fruit or cheese.

There is a lot of passing around of food. Judith will take a spoonful and pass it to the others, saying “Here, taste this,” challenging them with her eyes to be afraid.

One afternoon, three weeks after her first chemotherapy, Judith is sitting at her desk in the library. She passes her hand through her thick, curly brown hair, hair so curly a woman asked her at the movies where she had gotten such a wonderful permanent. She is prepared for this. She passes her hand through her hair and thick clumps of it come out in her hand. A librarian drives her home where she brushes the rest of it out with a brush, and ties a scarf around her head. With Kirby and Frances, she decides she will not wear a wig. She wears scarves for the rest of her treatment, and is as striking as a fashion model, Kirby thinks. As for the nausea, she says, “So I throw up for two or three hours, what’s so bad about that?”

Within three months the lung tumors have disappeared. She continues the chemotherapy, five days of every month. She doesn’t miss. She continues ordering books and writing poems. One day Jack Myers, a poet at Southern Methodist University, gets a note from her about library business. She writes a small poem at the end. Myers calls her up. Poets have got to stick together, he says.

“Before you meet me, there’s something you have to know,” she says.

“You’re sick,” says Jack. “You have cancer. That doesn’t matter.”

“I’m dying. I have maybe a year to live.”

They meet on a kind of blind date. She wears a red scarf.

“Want to see what I look like?” she asks in the car.

She takes off the scarf.

“You look great. Okay.”

They go to a bar and talk poetry.

Judith has a crush on Jack, but nothing comes of it. They settle in as poetry pals. She takes his poetry workshop in the spring, sitting in when she is up to it.

“I’m very smart,” she tells him. “I’m very bright, and I’ve read a lot of poetry, but I need help technically.”

It’s a deal. Jack promises her that he will be mercilessly critical, demand the utmost. She responds by working hard. When the new poetry books come in to the library, Judith reads them hungrily, phones Jack up and gives him a critique, a kind of poetry hot line.

She’s also hard on Jack’s poems.

“This line stinks, Myers,” she says. “Sometimes you write brilliantly; some-times I don’t know.”

Talking to Judith is like sticking your finger in a light socket, Jack thinks. She elevates the poetry class. And she keeps zinging him.

“Myers, you don’t know how good you are. If you did, you wouldn’t write like this.”

She zings him and leans back and says, “What do you think of that?” and challenges him with her hazel eyes.

She is writing out of rock-hard despair, Jack knows, because she believes she hasn’t much time, and she has a lot to learn about making her poetry sound and sing. At this rate, in five years she could win a national reputation, he thinks.

Poetry is not decorative, she writes in her notebook, but is chaste and desperate. It is an attempt to pare away lies, then find a core of lies that can’t be touched and are acknowledged as necessary. By turning toward the process, the poet tries not to get an ultimate, definable truth, but a sentence, a phrase, a picture, that is perhaps a little truer. Humility is necessary, and she underlines the resemblance of the words, humility and human.

“AND A SENSE OF THE SMALL-NESS EVEN FUTILITY OF THE JOB,” she writes in block letters in a notebook. “AFTER ALL, A JOB, SMALL INTENSE TOUGH JOBS, ARE (MAYBE) THE PROPER HUMAN ACTIVITY.”

Jack compares the writing of a poem to the challenging of an obstacle, a wall. Tunnel under it, punch through it, leap over it, dissolve and pass through it. Judith writes a poem about this that ends:

Over, under, or through,

it matters only

like the tombstone says this

person was and isn’t it matters

because we want to get it

get it right it matters just

a little to the wall.

She writes him a note that ends: “Your class is lovely, makes me happier than ever to be still whinnying.”

She writes in a notebook: “I could write a list of hates to fill this page: all people. I leave it blank and try instead to allow blankness to seep into me: to have a good heart.” She draws a heart on the page with an arrow through it.

She draws close to Kirby and then backs away, afraid to be too close to him, wanting to. Afraid that if they become too close, the pain will be too great if the cancer takes her away and afraid that it will be too much for him, that he will back out. Judith does not want any of her friends to back out. Instead she and Kirby delight one another. When Judith is depressed, Kirby picks her up and they drive into the country, walk along a creek bed, say little. He fixes things for her. When he unsticks the windows in her apartment, she warbles his merits to her friends.

When the ice storm of 1979 hits and Judith loses all the power in her little duplex on Palo Pinto, Kirby arrives with hurricane lamps and a Coleman stove. A tree on her street cracks and splits, and she writes a poem about it, thinking of her own possible death. Kirby digs a garden for her. She plants tomatoes, lettuce, onions, beans, and her poems acquire vegetables.

Kirby and Judith develop an ironic stance to the possibility of her death. She clowns in the Civil War cemetery near the convention center. Behind an old tombstone she stands in jeans and red sweater, as though to say she is not frightened. She has a little triptych of the photographs made there and sets it in her living room.

She writes Frances a birthday letter in the fall, four typewritten densely worded pages about love and work. Judith believes it is possible to have both, will not give up on either one. She sees her life as a poem she is writing, and though the poem won’t be perfect, it is the living of the poem, the loving and the working that make it possible to continue. “Only the work counts, the conversation between you and yourself.”

The circle of friends sustains her. She finds a poem by Charles Wright that she likes well enough to copy and keep around. The last stanza could be about her friends:

This world is a little place,

Just red in the sky

before the sun rises.

Hold hands, hold hands

That when the birds start, none

of us is missing.

Hold hands, hold hands.

Contingency: Dallas, Spring 1980-Jan. 1981

Listen to this, Miss Bell: Contingency (fourth definition, Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary.) “The fact of existing as an individual human being in time, dependent on others for existence, menaced by death, dependent on oneself for the course and quality of existence.”

By New Year’s 1980, Judith has spent 18 months in full remission. She has to stop taking adriamycin but continues to take other drugs. Her hair begins to grow back, at first, a fine, sparse baby’s hair. Judith is pleased.

Within three months, she finds a lump in her leg. It’s removed and found benign. Then another appears. She shows it to June in the restroom.

Frances is on the phone at the reference desk when she sees Judith walk off the elevator. She has returned from the pathologist and gives her a look of despair.

Weisberg has nothing left to treat her with. He suggests she go to Houston’s M.D. Anderson Cancer Clinic for tests and recommendations. She does, but they have nothing to offer, not even an experimental therapy. The only thing she can do is begin another course of adriamycin and have her heart monitored electronically.

“I’m really scared,” she tells June. What should she do about taking the adriamycin, she asks.

“I would like to see you here as long as I can,” June says.

“That’s what I want to hear.”

She dreams she is in an upstairs bedroom like that in which she grew up. She tries to turn on the light, but it won’t work. She tries lamps, one with a three-way switch, and flashlights. The bulbs are there, the switches sound right, but nothing will light up. She wants the light on because she can’t sleep.

It is being in the dark and unable to do anything that bothers her. She wants to be able to at least define the darkness, give it boundaries. Cancer is an experience of being out of control, with no explanations, no understanding. She writes the dream down in an attempt to understand, knowing already the limits of understanding she can get from writing.

She decides she needs to learn to float, to accept the unavailability of explanations and to trust her past experience of the limited nature of all things.

She sends Frances a note with some lines by Adrienne Rich that expresses her gratitude for her loyalty:

But gentleness is active

gentleness swabs the crusted stump

invents more merciful instruments

to touch the wound beyond

the wound

does not faint with disgust

will not be driven off

Judith begins preparing for her death. She has a list with 20 names titled, “People willing to spend nights.” She convenes a meeting with a hospice worker and several friends. She fears most that her death will be taken out of her hands. She wants to die at home in Dallas, and not be sent to New York, where, she fears, her parents would take over.

“Who thinks it would be a good idea for me to go home to my parents?” she asks the meeting.

Frances says maybe it would be a good idea not to close that door. Judith is furious. Frances is so upset that she has to leave the room.

No one wants Judith to leave.

Caring for Judith during her chemotherapy has already been exhausting. Frances is not sure they will be up to handling her death. Making promises is fine when Judith is still in relatively good health; she wonders whether they can handle a prolonged, serious illness.

It takes days for the breach to heal.

Judith makes Sandy a signatory for her bank account. She draws up a will and names Frances executrix. The will includes not only her savings and automobile, but also her baskets, jewelry, post card collection, Navajo blankets, books, even a rosary the unbelieving poet wants to send to a friend in Florida. She secretly writes the names of friends on slips of paper and places them in her Indian vases.

A tumor difficult to detect presses on her sciatic nerve, giving her severe pain in the hip and leg. Nina and Judith dub it the “tushy monster.” That summer she begins taking dilaudid, and when the pain intensifies she takes liquid morphine, a grape-flavored, purple elixir she dispenses from a plastic squeeze bottle into a measuring spoon.

In the midst of her despair she has good news. She phones up Jack, saying she has had a poem accepted by Harper’s.

“What d’ya think of that, Myers?”

Harper’s takes “Water,” part of a six-poem sequence called “Mending the Circle”:

There is always a journey

to the sea, friend.

Put my bones in a good jar

for the salt is very hungry

and I want to rest

a while on the water.

Waves, like the cool white hands

of my dreams, lift me, carry me

home.

One night she dreams that she is with all her women friends and some little girls on a grassy hill. They wrap themselves up in quilts and roll, laughing, down the hill.

Judith takes Nina shopping for a birthday present. She insists she pick her own Guatemalan huipil.

Nina is overwhelmed, doesn’t feel deserving, and can’t choose.

“Make up your mind,” says Judith. “I won’t be able to do this much more.”

“It’s too nice,” says Nina. “I feel funny.”

“That’s your problem,” says Judith.

Judith continues to work at the library, but sometimes she needs to rest while she reads. A cot is set up in a back office for her. Her colleagues do part of her work for her.

She walks with a limp from the tumor in her leg. After four more months of chemotherapy, the tumors show no signs of disappearing. Some are removed surgically, to relieve the “tumor load” from the chemotherapy, but the others persist. They show up in her lungs in the X-rays.

The doctors and she decide to stop the chemotherapy. She has some signs of heart damage. Nothing can be done except take medication for pain, and wait. She insists on working as long as she can. She organizes her poems into a manuscript and binds 30 copies into folders for her friends. The title is This Leaving We Cannot Live Without. She plans to enter it in a poetry contest. She is disappointed she can’t attend Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont that summer.

June and Frances organize a new schedule so that someone is with her constantly. They figure that two of them will need to be with her every night. They begin to wonder if they can do it. They are already exhausted from the long months of chemotherapy.

Judith stops going to work Nov. 11. Within three days she has to be catheter-ized. Her world becomes her bedroom with its ugly blue-green paint and dirty ceiling tiles. Her friends want to paint it, but Judith refuses. She insists that absolutely nothing in her house be changed. She will command from her sickbed.

One of her best poems, “In the Swaying Field,” is a metaphor for what she does. It’s based on a story Kirby has told her about a man who commanded two dogs in a field by hand gestures alone. Like a conductor leading an orchestra, he directs them across the field, circling, dancing.

The pain becomes worse, and Judith wants more morphine. Helpless to cook for herself, clean herself or care for herself, she at least has command of that. Her friends are troubled that she is taking so much she is nearly incoherent. June and Frances are exhausted and worried.

Judith wakes up from dreaming and June’s there.

“Was it real that I had the baby?” she asks. “Or is dying from cancer real?”

June hesitates for a terrible moment.

“The dying from cancer is real,” says June. “Come on, I’m going to give you a bath and then breakfast.”

Frances thumbs through the insurance booklet and discovers rescue. The library’s medical insurance provides for around-the-clock nursing. Within hours, Pinkie Cotton, L.V.N., is at the duplex on Palo Pinto.

She is a large, calm, competent woman. She surveys the situation and goes into action. The friends are loving but hopeless amateurs compared to Pinkie.

Her first words to Judith are, “You’ve got to wake up and look around.”

In Pinkie’s mind, Judith is wiping herself out with drugs. She wants her alert, at least part of the day. Pinkie shares the duty with Florence Bates, who takes a similar, loving, hard-headed approach. Neither of them can be manipulated, especially by Judith.

The house is a constant scene of friends visiting. Someone usually spends the night on the “marshmallow,” a long, white Naugahyde sofa Judith found at a garage sale.

Florence looks at the spare furnishings and improvised bookshelves and tells Pinkie that Judith must be poor.

“See these crates around here?” says Pinkie, pointing to the bookshelves. “That’s not poverty, honey, that’s art.”

When Judith cuts back on her morphine, she starts living a little more, hurting a little more. She commands the cooking, orders up the ingredients for tuna salad, and mixes and stirs the bowl while in bed.

Although her friends fill the house with food, Judith plans menus and insists on eating her food when she is hungry.

She puts on her makeup, carefully, professionally. She gropes for cosmetics in a shoebox and makes herself up lying flat on her back. It takes as long as an hour and a half.

The tumors spread onto the surface of her abdomen. Another swells behind her liver.

Shortly after the nurses come, Judith stays up one night, chanting like an American Indian.

She takes amphetamines to counteract the drowsiness produced by the morphine, but this appears to sometimes make her delirious. But she doesn’t stop being herself.

Once she hurts Frances’s feelings and Frances turns red.

“When you get mad you smell like an apple,” says Judith. “Don’t you want to hit me? Don’t you want to punch me?”

“I don’t express my anger that way,” says Frances.

“I don’t know why you put up with this.”

“Because you know she’ll take it,” says Pinkie.

Barbara Orlovsky, a poet and mother of three children, comes frequently and reads to Judith. At first Judith believes books are the answer. She sends a note to the library asking for fiction titles:

“This is HIGH PRIORITY — over food, laundry, back-scratching, feet-rubbing, etc., and just under morphine in importance.”

To her distress, she can’t read them, though the librarians pile in nearly 200 books. She thinks if only she can find the right book, her confusion will end. Being read to and talked to works better.

It bothers Judith that she is not loved completely by a man. One day Kirby comes over, and she shoos everyone out of the room, and insists he get into bed with and hold her.

But she also thinks she would refuse any man who loved her, because she couldn’t stand the failure. Pinkie says she is wrong.

“But it wouldn’t be fair to him,” Pinkie says, “if he’s willing for happiness, even if only for a week or a month.”

Judith develops an ironic stance to the possibility of her death. In the Civil War cemetery, she clowns behind an old tombstone.

Judith cuts her off. She is hard to talk to, hard to comfort, and deeply suspicious. Pinkie knows how to talk to her. Judith has to be the leader. If she wants to talk, Pinkie lets her.

One day Sandy is sweeping the floor, and Judith tells her to stop.

“I never sweep. The dust rolls up against the baseboard, and I smooth it out of the room with my feet.”

Thanksgiving is bad. Too many people are gone out of town, and Judith feels miserable and disappointed.

She has thought about suicide for months and has even saved up a stash of Seconal, but by December, it becomes obvious that she has waited too long. She’s having trouble swallowing now and she would need alcohol — and help. When someone asks her if she doesn’t yearn for peace, she says, “I can’t believe you asked that question.”

She declares to Pinkie that she will die between Christmas and New Year’s. Her breathing is heavy and gasping, in part from the morphine, which depresses the central nervous system.

She has forbidden the holding of a funeral service, but Barbara asks if they can have a memorial reading. She agrees and starts picking poems and songs.

Dec. 17 is the beginning of Hanukkah. Barbara brings her children, and they light the candles. Judith directs the making of potato pancakes and shortbread cookies. She comes out in the wheelchair in a white nightgown trimmed with blue lace to watch Barbara’s children light the candles. She learns a song from Barbara and her children and sings it for Frances on the telephone.

I had a cow down on the farm.

Golly ain’t that queer.

She gave us milk without alarm.

Golly ain’t that queer.

One day she stood in an icy stream.

Golly ain’t that queer.

Froze her tail clear up the seam.

And now she gives us all ice cream.

Golly ain’t that queer.

All this time Judith keeps her parents away, but her friends tell her they will summon them when the time comes. One eye is swollen and blurred. Her face is yellowish and dark with pain. She says there is nothing of her left, but her friends insist she is there and she must not doubt herself. When Barbara reads her some Psalms, Judith punctuates them with “B.S.” and “Not True,” but has her keep on reading.

Although she attacks Christmas as a hypocritical time of gift giving, Judith strings colored macaroni and popcorn and decorates a small tree set on the wheelchair and pushed close to her bed. She sends out for a bag full of spices and makes potpourri. She fills every available chatchka in the house, including a Moosehead beer bottle and Chinese slippers, and invites her friends to choose. She delights in watching them choose.

She becomes more and more conscious of everything she eats and excretes. She doesn’t want anything disturbed. She puts a note on the clear plastic catheter bag:

“Please keep this bag where it is. We understand some important things are not attractive. In this case, gravity greatly enhances the eliminatory function. So let me repeat, do not move the bag to the other side of the bed.”

Toward Christmas she grows worse. She is retching. Her eyes are purple and defiant and angry.

“I love you very much Judith,” says Barbara.

“Shut up.”

“I want to say something. I must be very careful. I don’t want to be corny.”

“Don’t be corny.”

“By being so much yourself you’re giving us a lot.”

“I’ve never felt less like myself. I want you to know I am shitting all over the place.”

Two days before Christmas it doesn’t seem she will last much longer. Frances calls Judith’s parents, David and Ruth Steinberg, who rush to the airport. Nina, who grew up knowing the Steinbergs, meets them at the airport. When she phones Judith’s house from the airport, there is no answer, and she fears she is taking the Steinbergs to a dead child. When they get there they discover someone has kicked the phone cord loose from the wall. Judith stirs.

“Hi Dad, Mother. What’s the bad news?” she says.

“We’re here with you, Judy,” they say.

Judith picks up a little. Her parents insist that everything will be the way Judith wants it. Her dad fixes the car; they both run errands. To give them a shopping list is to make them happy.

Two days before the new year, Judith insists on being taken to the porch in the wheelchair. She is gaunt, her belly bloated; the tumors pebbling her skin are frightening. She is wrapped in a bright patchwork quilt and wears a straw hat, blinking in the wind and sun. She is happy to have friends there, all women.

“I can’t think of one man I want here,” she says.

“Not even your grandfather Steinberg?” her mother asks. “He was a nice man. During the war he took me out to dinner every night.”

“And tried to put his hand up your dress.”

“He never put his hand up my dress.”

“Oh come on, Ma, tell the truth.”

“He wanted to stay alive to play pinochle with you.”

“I would have beaten him.”

What about X? someone asks.

“A shit. He came to visit every two years.”

How about Wade?

“He had to be nice, he’s June’s son.”

Kirby?

“He’s nice.”

Dr. Z?

“Ah. There’s a man. But he’s not too bright. He’s nice though. But not too bright.”

What about A?

“You want to know what I liked about A?”

His intelligence? someone guesses. Gentleness? His cleanliness? His tennis?

“Yes, I’d rather watch him play tennis than almost anything. He gave it everything he had. He didn’t hold anything back. But there was nothing you could do to get him to put his hand up your dress.”

A week later she is depressed. She longs to go to the garden but is too weak.

She cries because she is so young and hasn’t had a baby.

“I would really like to be a mother,” she says.

“I’ll let you adopt my grandbaby,” Pinkie says.

“Are you kidding?”

Pinkie takes a photograph from her purse and shows Judith the baby.

“I don’t mean you have to sign papers, but from my heart to your heart, this could be your baby.”

Judith cries.

Judith’s constipation is bad. Her belly swells. She is in danger of dying of her own waste. She is in and out of sleep by the third week in January.

When she is about to be moved and appears to be sleeping, Sandy proposes they wait until she has swallowed a bit of bread she asked for.

“That’s right,” says Judith, with her eyes still closed. “She may appear to be asleep, but she’s no dummy.”

Sometimes she thinks she’s not in her house and has to be reassured.

“Why do you think you’re in Australia, Judith?”

“Beats my ass.”

She decides that the cat is not her cat but another one that came in the mail, and looks like Sadie and wears Sadie’s tags. She demands the cat be kept away for a couple of days, and then, as abruptly, welcomes her back.

For three days she drifts between living and dying. Kirby comes in and holds her hand and feels enough pressure back that he believes she knows him from his thick, short fingers. Barbara brings in two yellow blooming branches of forsythia. A single tear comes from Judith’s eye. The other has grown swollen and red and tearless from the pressure of a tumor.

By the third week in January, Judith is in a coma. Thursday, Jan. 22, June and Frances rub her with lotions and leave for the night. Sandy is sleeping in the other bedroom. Florence is working the late-night shift. Everyone is exhausted.

Sadie is nervous. She paces around the room and jumps into Florence’s lap, which she has never done before. When Judith sleeps, her eyes are half open, the irises showing. At 2:30 in the morning, in a house blocks away, Barbara’s baby falls out of his crib with a crash and starts crying.

Florence goes to the other bedroom and awakens Sandy.

Judith is dead.

They call Frances and June. June gets there first and finds her as Florence found her. June closes her eyes and covers her with the blanket. Her parents come from the apartment they have shared with Judith’s friends the last five weeks. When the mortuary driver comes, they stand in the backyard until Judith is carried from the house.

Judith is cremated wearing her silver, hooped earrings.

At a simple service a few days later, the poems Judith selected are read.

Frances sings a traditional “holler” that Judith loved:

Pay day, pay day.

pay day at Coal Creek this morning.

The last thing they read is a poem of Judith’s, “Spirit Song”:

This flute I’m playing

wakes the insects,

who are sleeping at my feet.

The plants in the fields

cry all night long

for their cousins.

Even the dew is anxious.

What sounds in the dark

is not some gentle mewing.

It settles, small and wet, in the folds of our clothes.

There are ladders

in the air, and circles.

What creature isn’t

listening, moving?

I tell you, I will not

leave you, though I sing

as you die. I heard this

in a song: pass it on.

Her ashes are sent west, and scattered in the mountains.

Author