Editor’s Note: This story was first published in a different era. It may contain words or themes that today we find objectionable. We nonetheless have preserved the story in our archive, without editing, to offer a clear look at this magazine’s contribution to the historical record.

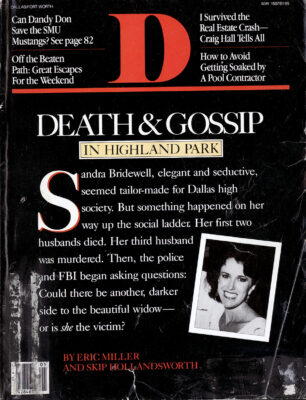

In a spacious apartment near the San Francisco Yacht Club, over-looking the bay, there lives a pretty woman who mostly stays to herself. She is 43 years old but looks younger. Always dressed immaculately, she carries herself in that calm, refined way of those who have known the comforts of money for a long time. Whenever she goes to the shops down the hill, her magnificent dark eyes lock onto the gaze of those she meets, and her smile is so natural that it can make men, even at a first meeting, feel oddly enchanted.

But here in Belvedere, a quiet shoreside village in posh Marin County, the woman keeps her distance. She comes to pick up her mail at a private mail box, and occasionally she eats lunch at one of the little restaurants that face the water. In the afternoon, she picks up her children at their school. Few of her neighbors have even met her. “She had this beautiful voice,” recalls long-time resident Silvia Davidson, who briefly leased a home to the new woman, “and she looked beautiful. But — how do I say this? She was like a mystery. She would say very little about herself.”

For Sandra Bridewell, the serene community of Belvedere, made up of 2,000 wealthy residents, is a good place to start a new life — a life without police investigations, endless gossip, and vaguely suggestive newspaper stories. Sandra Bridewell’s name might not mean anything in Belvedere, but in the wealthiest and most exclusive circles of Dallas high society, Sandra is the subject of intense speculation — by both her neighbors and the police.

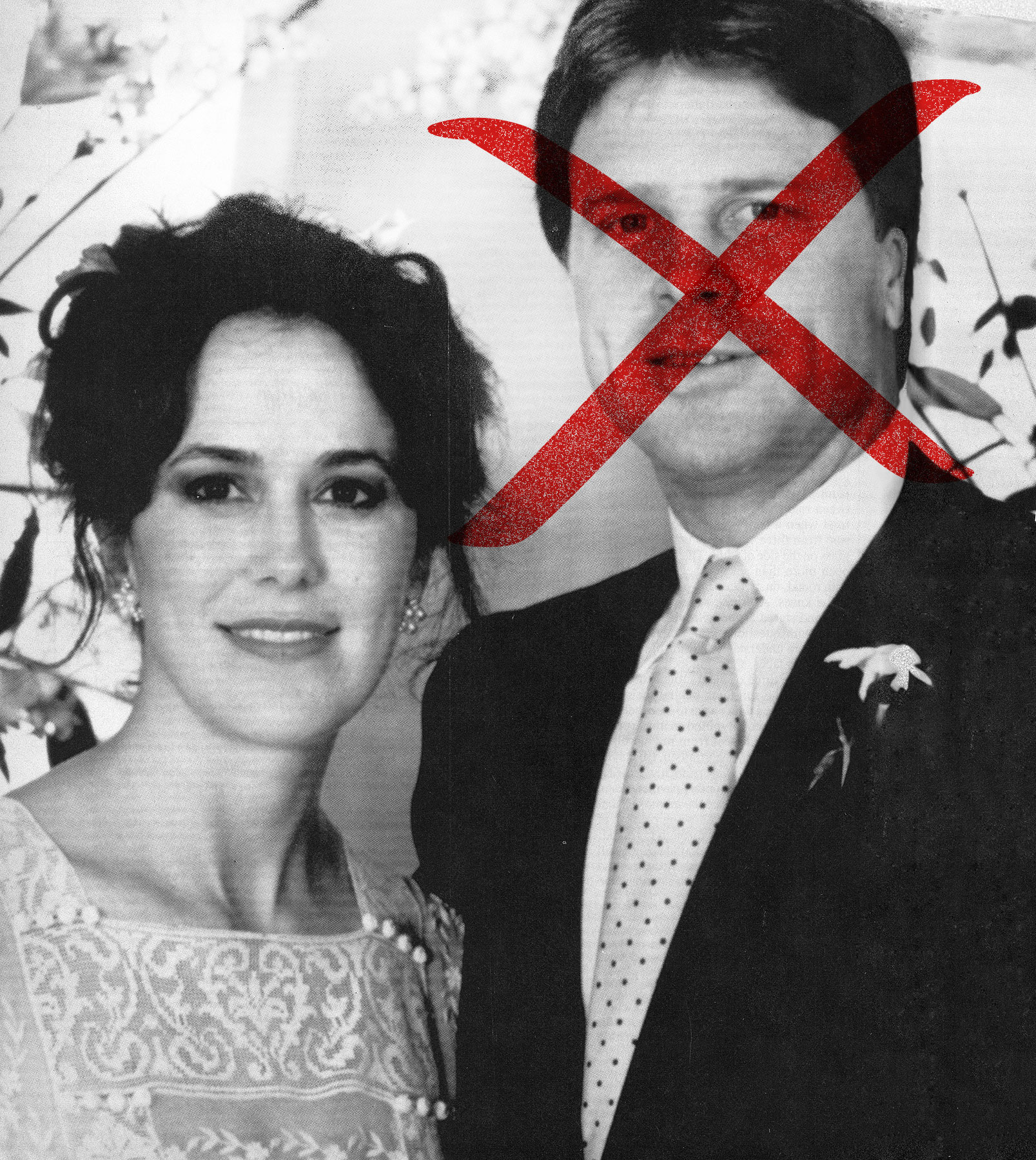

Three times she married, and all three times her husbands died. Her first husband, David Stegall, a young, talented dentist, shot himself to death in 1975. Her second husband, a popular hotelier and investor who conceived the luxurious Mansion Hotel on Turtle Creek, died of cancer in 1982. Her third husband, Alan Rehrig, a former college basketball star in Oklahoma who had come to Dallas to hit it rich in real estate, was found murdered in December 1985.

For a while, it seemed that Sandra Bridewell — an elegant woman who is regularly described by those who knew her as delightful and caring, who had raised three wonderful children and devoted herself to charities and taken an active interest in the arts — was also the victim of a very cruel twist of fate. Tragedy hounded her relentlessly. “You look at her,” says friend Barbara Crooks, a Highland Park native, “and wonder how she has withstood it. Despite everything that has happened to her, she has had to hold up and continue raising those kids.”

But since the murder of her third husband, Alan Rehrig, whose body was found in Oklahoma City, Sandra has had to endure something else. The police are interested in her. Oklahoma City homicide investigators say Sandra Bridewell herself is a suspect in the death of her third husband. Now, in a highly unusual move, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has joined the murder probe and is looking not only at the Rehrig murder but deep into Sandra’s clouded past.

Throughout the spring, FBI agents have been searching for clues to Sandra Bridewell’s personality. They have gone so far as to try to find a paper that Sandra allegedly wrote in college dealing with murder, guilt, penance, and salvation.

The FBI has also heard about the other bizarre death that touched Sandra, one that many people in the Park Cities have been whispering about for a long time. Two months after Sandra’s second husband, Bobby Bridewell, died of cancer, Dallas police found a Highland Park woman named Betsy Bagwell in a Love Field parking lot with a bullet in her right temple. The dead woman was the wife of the prominent cancer doctor John Bagwell, who treated Bobby Bridewell throughout his illness. During that time Sandra became very close to the Bagwells. She was, in fact, the last person reported seen with Betsy, less than four hours before her body was found. Betsy’s death was officially ruled a suicide, but those who knew her well say they cannot believe that she actually pulled the trigger.

The investigators have yet to present evidence to a grand jury that would link Sandra to any crime. Nor have they arrested anyone, but that has only added to the intrigue. Few can remember a time in the history of Dallas’ wealthy circles when the circumstances combined to produce such a sensational story — involving an attractive young mother, the men who loved her, and the affluent society that enveloped them. “There was something about her that you just couldn’t ignore,” says Diana Reardon, whose husband is a well-known Dallas home builder. “She would become very close to you, she would hook her arm around your arm when she talked to you. I’ve seen her charm entire groups of people. It was like she seduced them.”

Sandra Bridewell is now a target of constant gossip. Long lunch conversations at the Dallas Country Club are devoted to her past. A group of women, all wives of prominent businessmen, call themselves the “Snoop Sisters” as they track the latest Sandra story. Another well-known woman from one of the state’s old-money families keeps a thick file on Sandra’s doings. They are not alone in considering Sandra Bridewell guilty until proven innocent.

FBI agent Jon Hersley, who is in charge of the case, must be amazed at the attention paid to Sandra. Whenever he shows up at someone’s home for an interview, phone lines begin buzzing all over the Park Cities. In fact, it was Park Cities gossip that drew the authorities to Sandra in the first place, She became a suspect in the death of her third husband when the police got a phone call from an anonymous woman, called “the Highland Park Deep Throat” by one of her friends. The unknown caller spun a tale of mystery that was plausible enough to warrant further scrutiny. As word spread of the investigation, many Park Cities residents began to wonder if the Sandra Bridewell they thought they knew had another, darker side.

But others are quick to defend Sandra. They believe that a flood of unfounded gossip was ruining Sandra Bridewell’s life in Dallas. To Sandra’s defenders, the real crime has been committed by a Park Cities rumor mill operating at dizzying speed. “Highland Park is like a small town,” says Carolyn Day, a Bridewell friend who operates the popular Travis Street Market. “Everybody talks. It’s part of life here. I think it’s like that game you play where people sit in a circle and one person starts a rumor and passes it on down the line, and by the time it gets back to him the story is completely different.”

“Everyone has just jumped on the bandwagon against Sandra,” says another of her friends. “And they don’t even know her. It’s so ridiculous what is being said about her, so far from what she’s all about. People have conveniently forgotten all about the Sandra who once was their close friend.”

Last year, feeling the pressure of a community that scorned her, Sandra moved from Dallas to California with her three teenaged children. The rumors had done their work. Sandra was embarrassed to go out. Some mothers told their children that they could no longer carpool with Sandra’s two daughters. They were being frozen out of their society. Recalls her friend Suzanne Sweet, who now lives in California, close to Sandra: “There are several of us who said to her, ‘You can’t do this to your children. The other kids will rip them apart. Highland Park is not going to give up hurting you.’

In time, the police and the FBI will finish their investigations. But whatever their findings, many Park Cities people will go on believing that Sandra Bridewell is guilty of at least one murder. The story of Sandra Bridewell is perplexing and fascinating, like one of those Renaissance paintings in which the woman’s face is half in shadow, half in light, a tableau of innocence blending into mystery, perhaps evil. The fact that people gossip about her does not mean she is guilty; nor does it mean she is innocent. Sometimes rumors build from nothing. Sometimes they are the advance guard of the truth.

“There are times when I’ve lost sleep because of what has been said about Sandra,” says a respected Highland Park woman. Last February, the FBI interviewed her about Sandra for an entire afternoon. “I know there is something very, very different about that woman than the rest of us. But then there are times when I wake up at night and wonder, ‘What if she had nothing to do with this after all? Then what have we done to her?’”

HER BEGINNINGS

“The times she’s talked to me about her past, it’s like she thinks of herself as Cinderella.”

–former friend Diana Reardon

The Sandra Bridewell who is the target of both gossip and police scrutiny did not have her roots in Park Cities society. In fact, the beguiling woman who loved champagne and trips to New York, who drove expensive cars and took gourmet cooking classes for fun, had no silver spoons during her childhood. Her early years were steeped in turmoil, and they contained no small amount of tragedy.

She was born in 1944 in the little town of Sedalia, Missouri. Given up as an infant by her natural parents, she was adopted by a couple who could have no children of their own. Her adoptive father was a man named Arthur Powers, the owner and manager of the local Dr Pepper bottling plant. Her adoptive mother, Camille, was killed, reportedly in an automobile accident, when Sandra was about 3 years old. Her father soon remarried. When she was 6 years old, Sandra and her family moved from Missouri to a middle-class neighborhood in Oak Cliff, where her father sold cemetery plots for Laurel Land Memorial Park.

As Sandra grew to adulthood, the memories of her early childhood days would become a vivid source of conversation. Many of her friends and ex-friends can recall stories Sandra told of her unhappy youth. Susan Dreith, Sandra’s closest friend during her teenage days (she lived around the corner), says that Sandra and her stepmother “did not have a good relationship at all.”

“I remember how Sandra used to talk about a birthday party that her stepmother was throwing for her,” recalls a former friend who recently lived next door to Sandra. “The day of the party no one came. Sandra says it was because her stepmother forgot to send the invitations. Sandra would tell me that her stepmom would tell her that she was unwanted and had no friends.”

(Sandra’s father is dead. Doris Powers, her stepmother, would not be interviewed for this story. “I think Sandra’s been harassed enough,” Mrs. Powers says. “I don’t know why this is happening to her.”)

Sandra went to Kimball High School in Oak Cliff, graduating in 1962. According to Susan Dreith, she was always properly dressed with very nice manners — “sort of like an Eddie Haskell type” — but she was not very popular, nor did she seem involved in many activities. Her senior class photograph for 1962 does not even appear in the annual, and she is pictured in no other school organization except for the Future Homemakers of America. Dreith says that although Sandra’s beauty was well evident by this time, she didn’t date much.

“She seemed to be just on a pretty even keel,” says Dreith. “And she often seemed a little aloof — and yet there was this one thing that always made you wary. It was sort of like a deception about her. She would always make up stories about things. Now, I know we were all kids, and we all did that sort of thing sometimes, but Sandra was sometimes so ridiculous. One time, we were supposed to go somewhere on a weekend night, and I never heard from her. When I asked her about it, she said she had to leave for Missouri in the middle of the night. Well, of course, I knew that wasn’t true. She was over at her own house.”

Another intimate friend of Sandra’s, Paula Johnson, who got to know her when they were both in their early 20s, recalls Sandra’s habit of lying about her past. “Sandra never mentioned any of her friends from high school,” Johnson says. “I never met any of them. It was odd. There was this time when we were driving through a very nice area of Oak Cliff, and Sandra pointed to this very beautiful home. It was landscaped, it was by a city park, it was so lovely. And Sandra looked at me and said, ‘That’s the house that I grew up in.’ A couple of months later we had to go to her real house — I think it was for the funeral of her father — and when we got there, it wasn’t at all the house she showed me. How did Sandra think she could get away with that lie?”

Signs of deceit continued as Sandra grew older. Some people who have known her as an adult recall that Sandra claimed she attended SMU. The registrar’s office has no record of her taking any course at SMU. On her 10-year high school reunion questionnaire, Sandra wrote that she attended TCU. According to the school registrar’s office, she never enrolled at TCU.

It is documented that she attended Tyler Junior College for a year after high school, where she was a member of the local Sans Souci (French for “without care”) sorority. She returned to Dallas sometime after that, and by 1966 she was living the life of the young North Dallas single woman at the Windsor House Apartments near the Upper Greenville area.

Perhaps as a reaction to her uncertain, troubled upbringing, Sandra developed a taste for the exquisite and expensive things in life. Those who knew her in the ’60s say that even then she was striving for a kind of sophistication that others her age didn’t have.

“She was phenomenal to the rest of us,” recalls Kathy Woodson, a Dallas secretary who was part of Sandra’s crowd at the time. “She was this sort of Southern belle who had come out of nowhere. She had these real sweet manners, and she knew how to make flaming plum pudding. I mean, we were taking movie magazines, and she was taking Southern Living. She instinctively knew what men would want.”

With these charms, it didn’t take long for men to come flocking to Sandra. She began dating a young dental student who had ambitions to become a great dentist in Dallas. He lived in an apartment complex across the street from Sandra, and after just six weeks of dating, he asked her to marry him. In May of 1967, David Stegall became Sandra’s first husband.

THE FIRST HUSBAND

“They loved the idea of being rich. David liked rich things, and so did Sandra. But, being young, or whatever, they had no idea about money.“

–Dr. E.T. Stegall Sr., David’s father

David Stegall was a rather quiet, good-looking young man born and raised in Fort Worth. Following in the footsteps of his father, he went to the Baylor College of Dentistry, where he graduated with honors. But he wanted to do something more in his profession than run a family practice like his father had. “He was obviously set on becoming the big-time, society dentist of Dallas,” says a dentist friend of his who knew him in dental school and later had an office in the same building with Stegall. “He didn’t want to do normal stuff like fillings. He was into full mouth reconstruction, where some patients would get charged over $10,000. And that was an enormous amount of money back then.”

Stegall went to Los Angeles to study with a prominent dentist, Dr. Peter K. Thomas, who had a long client list of Hollywood celebrities. From Thomas, Stegall learned how to make all the right moves to attract the proper clientele. The newlyweds also joined St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church, which on Sundays is filled with some of the wealthiest people in Dallas. In Stegall’s new office at Douglas Plaza near Preston Center, there were Gittings portraits of his children on the walls.

David’s father says Sandra was David’s first girlfriend; he had never seriously pursued a relationship before meeting her. Says Kathy Woodson, who watched the courtship of David and Sandra develop: “David was a real sweetneart, but not a lot of people really liked him because he was a real loner and serious about his work. He never was the type that would have gotten involved in the high society life. But when he married Sandra, it all changed.”

From the beginning, Sandra moved easily into the upscale world, as if this were her natural element. “She was the most beautiful entertainer,” recalls Highland Park resident Marian Underwood, who once was a close friend of Sandra’s. “She was so creative in her home. If she had a little dinner party, she’d go all out for you.” She was a wonderful hostess, she made perceptive comments in the neighborhood book club, she was cookbook chairman for the St. Michael church (her recipe was quail in wine). “Her main goal was to be in the Junior League,” says Kathy Woodson. “She wanted to be the classic Junior League woman. I never really understood why she never got in.”

“She was trying to gain a lavish social identity,” says Jack Sides, who was the Stegalls’ attorney. “She wanted to do things first class.” One acquaintance of the Stegalls recalls a birthday party thrown for one of the neighborhood children. While the other mothers brought little presents that cost no more than $5, Sandra showed up with an elaborate $30 balloon arrangement.

Another acquaintance met David and Sandra Stegall in 1971 at a backyard beer-and-oyster party thrown by the noted Highland Park real estate agent Charles Freeman. She recalls that Sandra seemed offended when she was offered a beer. “She said that she didn’t drink beer,” recalls the woman. “That’s fine, but it was just the pretentious way she said it, you know. We could all tell she was trying to be a social climber.”

But the truth was, David Stegall also found himself enjoying the high life. He didn’t mingle well at parties, but Sandra was able to lead him through it. And the social whirl certainly didn’t hurt his dental practice. Finally, he was making some money: his income almost tripled, from $27,000 in 1972 to $68,000 in 1973. The Stegalls had caught a glimpse of the good life that belonged to Dallas’ old-money crowd, and they found it addictive. Soon they began trying to live like the people whose opulent parties they were attending.

By 1973, they had moved to the upscale Greenway Parks neighborhood, buying a $65,000 house that they quickly began to remodel at a cost of $45,000. Sandra was taking care of the bills at home, and David was heading off to work in a new 1973 Cadillac and a $300 sport coat. They got a live-in maid and had their groceries delivered from the chic Simon David grocery store on Inwood Road. They even looked into purchasing a much larger home in Highland Park.

As the spending escalated, Sandra paid the renowned Dallas interior designer John Astin Perkins $35,000 to redecorate the home with antiques. A dentist’s wife walked in and breathlessly said the house reminded her of the Palace of Versailles. One friend remembers that David and Sandra were quick to point out special touches like a little table in a corner that cost $4,000. Another friend, a member of Sandra’s church, recalls hearing Sandra say that her goal was to get her home featured in Architectural Digest.

By 1974, about the time the couple’s third child was bom, the debts were getting out of control. “They were literally talking each other into spending,” recalls one close friend. The IRS put a lien on their house forunpaid taxes. The Stegalls owed a North Dallas bank more than $30,000. David had stopped referring patients with simple dental problems to other dentists and begun doing the work himself. “He was working night and day to pay the bills,” recalls Paula Johnson, whose former husband, a dentist, also committed suicide. “I would ask Sandra why she would spend and spend, and she would say, ‘Well, David is doing so well.’”

But David Stegall was not doing well. A psychologist who had a counseling session with David a few days before his suicide recalls that David did seem “pretty put out by the bills for household furnishings … The wife seemed to have him in a very painful box. He was completely intimidated by her. The idea, as he saw it, of his inability to pay the bills, stood in pretty sharp contrast to his professional skills.”

In the fall of 1974, the financial picture worsened. David borrowed $100,000 from his father to try to stay above water. But the problems were affecting David’s work in the office. “You could tell that the quality of his work was deteriorating,” recalls an associate, Dr. Paul Radman. “I didn’t know anything about his personal problems, but I knew something was wrong.”

One friend remembers how David, in the final weeks of his life, talked about moving to California, buying a Porsche convertible, and finding a young blonde. Life at home was miserable. Sandra and David argued constantly. Paula Johnson remembers that Sandra accused David of having an affair. One time Sandra came over to another friend’s house with a black eye and said that David had hit her. Sandra had begun to sleep in the children’s bedrooms; friends say she was scared of David’s “violent” temper. Late one night, about three weeks before Stegall actually killed himself, his attorney, Sides, got a frantic phone call from Sandra saying that David was drinking heavily. Sides rushed to the house and found Stegall crouched in a closet pointing a pistol at his head. Sides took the gun away from David without a struggle.

After that night, Stegall told friends that everything was fine and said he would never try suicide again because of his love for the children. But on February 22, 1975, David did try again. This time he succeeded. Sandra told police she was sleeping in another wing of the house and awakened to find David lying in his bed in a pool of blood. Police found the dentist with his wrists slashed and a bullet wound to his left temple. A .22-caliber pistol was in his hand. Later, police would discover that the gun Stegall used to kill himself had apparently been stolen from one of his patients.

Sandra sold the home for $147,500 and got $160,000 in life insurance. Her dead husband’s dental practice sold for less than $15,000. Even after paying off all the bills, she and her children had enough money to live comfortably.

Neither a psychologist nor a psychiatrist who had examined David Stegall days before he died concluded that he was suicidal. But to Sandra’s dismay, David’s own problems didn’t stop many of David’s friends from turning against her. “At David’s funeral,” says Kathy Woodson, “all of the old gang sat around and talked about how David tried to take the charge cards away from Sandra because he felt she was driving him into ruin.”

One of Sandra’s staunchest defenders from that time admits Sandra painted “a fantasy-land portrait of life.” Tragically, that fantasy — of a prosperous little family on the way up in Dallas’ wealthiest community — had come to a shattering conclusion. For Sandra, it was time to pick up the pieces of her life and start again.

THE SECOND HUSBAND

“Here you are, a housewife worried about carpools and working at the school cafeteria, and along comes Sandra talking about someone throwing knives at her. None of this had ever happened to us.”

–Frances Shepherd, Highland Park mother

When David Stegall died, Sandra Bridewell was left with her 7-year-old son and two daughters, ages 4 and 1. She had no job. To some who knew her, it seemed as if the pretty young widow had nowhere to turn except to another man.

“She would often talk about men,” says Diana Reardon, “and how she needed men, and how her children needed a family. I mean, it was perfectly understandable. Sandra looked for men the way other people looked for a job. In the position she was in, it was her way of surviving.”

Some old friends of David Stegall’s resented Sandra, but many friends and neighbors were ready to help her. In time, Sandra began to go out again. And the Highland Park wives who set her up on dates with their wealthy divorced friends discovered something very quickly: Sandra, voluptuous and bewitching, was remarkably appealing to men. She knew how to flatter them, and she knew how to flirt with them. Those who have taken her out describe her allure in many ways — one calls it a “wonderful little-girl aura,” another calls it a “calculated femininity.”

Men looked upon her as they looked upon money: she was one of those things in life that was impossible to understand and useless to resist. “She had this sexy look to her,” recalls Lynn Price, the Highland Park woman who arranged Sandra’s first date with Bobby Bridewell, the man who would become her second husband. “It was sort of a smouldering style.”

“It wasn’t that she dressed in a provocative way,” says Yvonne Crum, a well-heeled Dallas socialite and public relations consultant. “She wasn’t that much prettier than other women. But men were spellbound by her. She had those great big eyes, and she’d stare straight at a man while talking to him, hanging on to every word, and it made him think he was the only person in the room.”

There was another thing people soon learned about Sandra. She was not shy in going after someone she liked. Says one friend who became close to Sandra after Stegall’s death: “Three months after David died, Sandra mentioned three men she wanted to meet. All of them were millionaires.”

Sandra’s defenders believe such stories are born out of jealousy. “It’s true Sandra has a few feminine wiles,” says Barbara Crooks. “Which of course makes her the type of woman other Highland Park women aren’t going to like. They don’t especially take to a woman who is warm and appealing.”

No doubt Sandra did make plays for rich men. Says a Dallas banker who introduced Sandra to a wealthy bachelor friend from Arkansas: “He came back from his date raving about her. Then he caught a flight back to Arkansas on Monday morning. Monday night he heard a knock on his door. It was Sandra. She had followed him home. It was an ugly scene because my friend was with his girlfriend when Sandra showed up.”

A wealthy Dallas investor met Sandra at Northwood Club in 1975. He recalls that she came on very strong right at the start. “She was sweet to the point of being gooey. I remember one time when Sandra and I double-dated with my sister. It was only our third or fourth date together. She was ‘honey’ this and ‘love you’ that to the point where I was embarrassed.”

Perhaps Sandra’s most notorious relationship after the death of her first husband was with Steak and Ale founder Norman Brinker, who began dating Sandra while he was in the midst of a drawn-out divorce proceeding. While dating Brinker in the fall of 1976, Sandra became the apparent target of a harassment campaign. On one occasion, her duplex was broken into, and a threatening message was written in lipstick on a mirror.

Several women also recall that Sandra told them about a woman throwing a knife at her. The stories created the kind of stir that almost never permeates the normally sedate Park Cities community. Brinker briefly hired a bodyguard to protect Sandra. Eventually she was dragged into his divorce; she gave a December 1976 deposition in the case. What she said remains a secret. Brinker won’t talk about her, and his divorce file is missing from the Dallas County records morgue.

And so, by the time Sandra met Bobby Bridewell, a fun-loving, likable hotel investor, she was already the object of great speculation. In the conservative Park Cities, where houses are filled with fine furniture and old paintings and maids, where mothers drive Suburbans and fathers leave work early to coach their kids’ YMCA soccer teams, Sandra certainly stood out. There is a comfortable emotion in “the Bubble,” as Park Cities residents call their own protected community: they know their lives will be safe and sheltered. Many of the residents grow up and die in the same neighborhood. Which is why Sandra was a very different entity altogether.

A lot of the talk was cruel. And the truth was that many women loved having her as a friend. They milked her for details, then burned up the phones passing on new tidbits. “You hung on every word of her stories,” recalls one ex-luncheon partner, “because you never knew how they’d end up.”

“The thing you have to remember is how narrow Highland Park can be,” says Barbara Crooks, who now lives in New York City. “I grew up there all my life, and I know what happens — you see the same people at the same parties, you do the same things, and you need something to liven up your life. People look for a great gossip figure. And that’s what happened to Sandra.”

But none of her past mattered to Bobby Bridewell, the son of a rich Tyler oilman who was beloved among his friends for his partying and wild sense of humor. “He was the master of the grand gesture,” recalls his friend, Dallas entertainment entrepreneur Angus Wynne. “He was a great lover of rhythm and blues, and he would go to all the concerts. Of course, he’d be one of the few white people in the crowd, but he didn’t care. He’d dance in the aisles and imitate the performers. Once he jumped up on stage and threw his coat around James Brown.”

When Sandra, who had been scheming to meet him for weeks, popped out of a closet one evening at Bo and Lynn Price’s home while Bridewell was there for dinner, he seemed utterly delighted. It was late 1977, and Bobby was going through an ugly divorce. His first wife had announced that she was in love with her horse trainer. Many of his friends knew how much the wrecked marriage had devastated him.

Sandra came along at the perfect time for Bobby Bridewell. She loved to go out as much as he did, and she made a point of sharing his interests. When she started dating him, according to one of her friends from that time, she read several books on horse racing, knowing how Bobby loved the sport. “Sandra knew how to indulge Bobby,” says her friend Carolyn Day. “She let him have center stage. He was quite the entertainer and talker, and she let him have his role while she took a back seat.”

After a whirlwind romance, they were married on June 26, 1978. “Bobby was swept off his feet,” says Bo Price. Another good friend, the noted Dallas architect Phillip Shepherd, remembers that Bobby, vulnerable from the divorce, needed companionship. “She was a different kind of girl for him. She doted on him. I think Bobby knew that Sandra thought she was coming in for a lot of money, but that didn’t slow up the relationship.”

What many didn’t know was that Bobby had been sliding into a major financial crisis. He was involved in dozens of joint real estate ventures in the hotel industry, and almost all of them were failing as the 1978 real estate market bottomed out. By the end of 1978 he was bankrupt and had fallen more than $3 million in debt.

Still, say his friends. Bobby refused to be discouraged, and by 1979 he was starting to turn things around again with a unique hotel project. On a drive one day by the old Sheppard King Mansion, a 16th-century Italian-styled villa, an idea flashed through his mind. Why not convert the villa into a pricey hotel and restaurant? He sold Carolyn Hunt Schoellkopf on the idea, and her Rosewood Hotels Inc. purchased the property. Bobby stayed on as consultant to see his idea turned into reality when the Mansion opened for business in 1980. By then, a bankruptcy judge had released Bridewell of all his debts, and he was back to a six-figure income again.

Quickly, Sandra Bridewell found herself thrust even higher into Dallas society. Bobby’s circle of friends, most of them in their mid-30s, were well on their way to becoming some of the most prominent businessmen and socialites in Dallas. Sandra was given the chance to do the invitations for the exclusive Cattle Baron’s Ball. She was given the best table and fawned over at the Mansion. When she traveled to Houston, she stayed at the chic Remington on Post Oak Park Hotel, another of Bobby’s projects.

Bobby even adopted her children, giving them the distinguished Bridewell name. She bought such lavish gifts for her new friends, says Phillip Shepherd, “that it just seemed a little too much.” Lynn Price says, “Sandra became even more glamorous. It was like she did nothing that did not involve the finest taste.”

Many of Bobby’s friends found themselves liking Sandra. “She had a magic spell on people,” says one woman who was close to her then. “You”d find yourself doing little things for her — running errands, taking her children places. Then you’d wonder why you were doing it, when you knew she was down at the Mansion having lunch.”

But the friends continued to help Sandra — especially after the shocking news came in 1980 that Bobby Bridewell had been diagnosed with lymph cancer. The ill-fated Sandra Bridewell, who seemed on the verge of establishing herself in society, was plunged into yet another tragedy. At first, Bridewell continued to work at his usual frenetic pace, seemingly undaunted by the heavy doses of chemotherapy he was receiving. But by 1981, he was losing weight and spending more time in bed.

To understand how Bridewell’s death made Sandra the object of more whispering and speculation, realize that Bobby Bridewell was adored by his peers. He was like a minor figure in a Fitzgerald novel, wearing loud sport coats, laughing harder than anyone in the room, always the last to leave the party. In a 1980 videotape of Phillip Shepherd’s 40th birthday party, a group of women sang a song in tribute to Bobby. The guests knew by then that the cancer was going to kill him, but they laughed and talked during the song. Still, even in the grainy footage, one can see Bobby’s friends look vacantly at him, as if lost. Nearby, Sandra sits on a couch, weeping softly with her hands to her face.

Bobby Bridewell’s last months should have evoked the kind of love and warm generosity that emerges in people during misfortune. Instead, a deep bitterness grew in Bobby’s friends, and it was directed at his wife — for while Bobby lay dying, Sandra Bridewell was remodeling their Highland Park home.

To some in the Park Cities crowd, Sandra’s actions were outrageous. “That winter before he died, the heat didn’t work in their home,” says a woman who was close to Bridewell. “And here was Sandra redoing her garden room and the wallpaper and what have you. So I brought over some spare electric heaters and a down comforter to make Bobby feel more comfortable, and Sandra wasn’t appreciative of the down comforter because it didn’t look pretty enough.”

“Oh, that’s a crock,” says Barbara Crooks in defense. “They were fixing up that house long before Bobby got sick. And he asked that it be done.” Says another lifelong Highland Park resident who couldn’t understand the complaints of Bobby’s friends: “Okay. Sandra’s actions might not have been the most appropriate thing to do, but it wasn’t like she was being immoral. Bobby’s crowd was just looking for something to hold against her.”

In the spring of 1982, Sandra asked Marian Underwood, a neighbor who was a retired teacher, if Bobby could stay for about a week in one of her spare bedrooms while Sandra had central air conditioning and heat installed in her home. Bobby never returned home. He stayed at the Underwood home for three weeks, until Bobby’s father got angry at Sandra and moved him into a suite at one of his motels, the Twin Sixties Inn on Central Expressway. Marian Underwood, who loved the Bridewells, also had a falling out with Sandra, as did many of Sandra’s friends who had taken care of her children or bought her groceries during Bobby’s illness, and felt little appreciation in return.

“Sandra was so demanding with your time,” says Diana Reardon. “She’d call you constantly and not get off the phone, or she’d come over and never leave. Even if you had something to do, she would stay and talk, no matter how politely you said that it was time for her to leave. It got to the point where you’d have to escort her to the door and shut it in her face. Then she’d call you up crying, telling you how terribly you treated her.”

Bobby remained in the motel room until late April, then spent the last two weeks of his life at Baylor University Medical Center. The remodeling continued on the house.

Bobby died at age 41 on May 9, 1982. A few weeks later, Sandra left for a Hawaiian vacation with her three children. She needed to get away from a world that had come crashing down around her.

Though Sandra might not have realized it, she was quietly being ostracized from her cliquish society. The talk was snowballing, bringing an avalanche of rumor and innuendo to bury her reputation. Sandra had strayed too close to the boundaries of good taste in the reserved Park Cities community. A few months later, the talk would become tinged with fear when one of Sandra’s friends was found dead in a Love Field parking lot.

THE DEATH OF BETSY BAGWELL

“Of all the interviewing I did, with all her closest friends, I could not find anyone who could think of a reason Betsy would have to shoot herself.”

–Bill Murphy, private investigator

Bobby Bridewell’s cancer doctor, John Bagwell, was one of the most distinguished physicians in Dallas, the kind of professional who would leave for the hospital before daybreak, come home at night for a quick dinner, and then go back to the office. His wife, Betsy, was the quintessential Highland Park housewife and mother. A former Highland Park High School cheerleader, Betsy worked on the Shakespeare Festival, belonged to the Junior League, was active at Highland Park Presbyterian Church, and taught a Bible class for children in her home while raising two children of her own.

“Her biggest goal in life,” recalls one neighbor, “was to have a No. 1 family.”

Betsy Bagwell lived the kind of stable life that Sandra Bridewell had long hoped to achieve. For whatever reasons, Sandra became very close to the Bagwells while Bobby Bridewell was dying of cancer. She depended on them as much after Bobby’s death as before.

One of Betsy’s closest friends, who talked to her shortly before she died, says that “it looked a little unusual how quickly she tried to get close to [John].” But Sandra also became very attached to Betsy, a sympathetic woman who was known for counseling and befriending many of her husband’s patients and their families. After Bobby’s death, Sandra even accompanied Betsy to Santa Fe for a short vacation. Sandra began to call Betsy “my new best friend,” says a Park Cities woman who knew both of them well during this period.

Nevertheless, the Bagwells were growing weary of her. Like many people who were once friends with Sandra, they felt she was trying to smother them, always asking them to do something for her. One Wednesday evening in July, Sandra telephoned Bagwell to tell him that her car had stalled while she was out running errands. Reluctantly, John agreed to assist Sandra. But when he got to the site, he saw a policeman getting into Sandra’s car. The car started immediately. Bagwell, who would later tell investigators that he believed Sandra had lied about the car trouble to lure him from his home, angrily told her to get out of their lives. He also told Betsy to stay away from Sandra.

But a few days later, on July 16, Betsy received a phone call from Sandra. According to a private investigator hired to look into Betsy’s death, Sandra was upset about a letter she had found written from another woman to Bobby. Sandra said the letter, discovered inside a frame behind a photograph, intimated that Bobby was having an affair. For Betsy, something didn’t seem right about the story. She told her husband about it that morning and brought it up again with two female friends over lunch at the Dallas Country Club. (Sandra has denied the existence of the letter to the Dallas police.)

According to police and private investigators, Betsy got another call that afternoon from Sandra. Again, her car had stalled, this time at a church, and she needed help. Betsy couldn’t say no. She drove Sandra to Love Field about 4:30 to pick up a rental car, but because Sandra had forgotten her driver’s license, she couldn’t get a car. According to police, Sandra said Betsy then took her back to her car at the church. Again, the car started. The police say that Sandra told them she then left Betsy and went shopping at Preston Center.

At 8:20 that evening, police found Betsy Bagwell in the terminal parking lot at Love Field, slumped in the driver’s seat of her 1980 powder-blue Mercedes-Benz station wagon with a bullet hole in her right temple and a .22-caliber revolver in her hand. The Dallas County Medical Examiner ruled the death a suicide.

No one who knew Betsy Bagwell could believe she had killed herself. According to investigators, Betsy had told her children early that afternoon not to “pig out” because she had dinner thawing in the sink. Moreover, the gun found with Betsy was a stolen Saturday Night Special, a cheap pistol registered to a deceased Oak Cliff man who had kept it in his glove compartment in his car. The man’s wife said the gun had been stolen sometime in the ’70s, but the couple never reported it missing to the police. Police and friends alike wondered how a woman unfamiliar with guns could come across a stolen handgun. Why didn’t Betsy Bagwell just go to a Highland Park sporting goods store and buy one?

But Dallas Police Department homicide investigator J.J. Coughlin, who supervised the case, says the county medical examiner called Betsy’s death “a classic textbook case of suicide.” Tests showed traces of gunpowder, blood, and tissue on her hand, leading to a ruling of suicide.

Still, those who knew Betsy were unconvinced. The death marked a turning point in the way Park Cities people regarded Sandra Bridewell. Suddenly, they were very apprehensive.

“When the first husband died, people felt sorry for Sandra,” says well-known real estate agent Thomas McBride. “When husband No. 2 died, they still rallied around Sandra.” But when Betsy Bagwell died, he says, people grew wary of Sandra. “She became quite a mysterious woman, and people were beginning to realize that the only things they really knew about Sandra were the things Sandra had told them.”

Was there another Sandra Bridewell, a black widow with a fatal bite? Or was Sandra a victim of circumstance, a maligned target of Highland Park rumors? Neither the police nor the private investigators found any evidence indicating murder. Friends report that Sandra seemed staggered by the deaths of her husband and best friend. If she heard rumors, she didn’t lower her dignity to address them. Remaining in the big Highland Park home Bobby had left her, she tried again to pick up the pieces of her life. She bought a new two-seater Mercedes, and she used the memorials given in Bobby’s honor, amounting to nearly $50,000, to help establish a week-long summer camp, run by Dallas’ Children’s Medical Center, for children afflicted with cancer.

Sandra met new friends, and things began slowly to move forward. Her own children, amiable, well-behaved kids, seemed to be coping adequately with the second death in the family.

And then, in the summer of 1984, she met another man. His name was Alan Rehrig. He would soon fall in love with her. And then, he too would die.

THE THIRD HUSBAND

“Alan’s mistake was that he wanted money fast. His mistake was thinking he could quickly become a part of Dallas’ high society — and that left him gullible.”

-Bill Dodd, lifelong friend

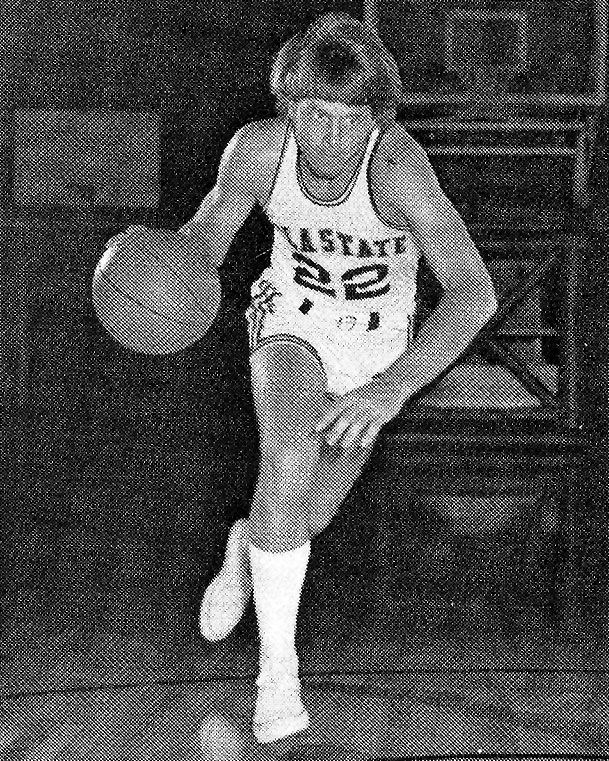

Growing up in the town of Edmond, Oklahoma, Alan Rehrig seemed to have everything going for him. They talked about him at the barber shop. Alan was the high school sports star who had made good, and as one of Sandra’s friends later put it, he looked “All-American cute.” His mother had a scrapbook full of clippings about Alan. Girls adored him. He became an All-State athlete in high school. On a basketball scholarship, he attended Oklahoma State University, where his mother was once homecoming queen. He also played on the college football team his senior year; a defensive back, he made an interception in the end zone during one game to save a victory for OSU. He became the first athlete since 1940 to letter in two varsity sports at that school.

With a teacher’s certificate in hand, Rehrig was planning to return to his home after graduation and work as a high school coach, just as his older brother did in another town. But just before he was to begin teaching at Edmond High School, Rehrig suddenly moved to Phoenix to take up golf, announcing that he wanted to become a professional golfer. Two of his old high school buddies had already made the PGA tour, and they persuaded Rehrig that he could do it too. Obviously, the move just didn’t make much sense — there was little chance that Alan would be successful as a golfer. But for a gifted athlete, the dreams of life in the arena don’t die easily.

For the first time in his life, Rehrig failed. He had to work nights as a waiter to make an income. After two years he returned to Oklahoma, where he decided to try the oil business, When the prices fell and the oil industry bottomed out in Oklahoma, Rehrig found himself out of money and looking for another job. His friends remember that he was feeling a little desperate. He was 29 years old, and he had gone nowhere.

In the summer of 1984, Rehrig decided to move to Dallas to work for an old college friend at Nowlin Mortgage. He reported to the commercial loan division, which acted as a broker between real estate developers and big life insurance companies wanting to invest their money. At a beginning salary of $24,000 a year, he started at the bottom of the ladder, running errands, doing the odd jobs. It didn’t seem like much, but he knew that down the road could come the opportunity to cash in on a big real estate deal.

The day after he arrived in Dallas, on June 2, Rehrig drove down Lorraine Avenue, one of the most beautiful streets in Highland Park, looking for garage apartments that he heard were often available behind the mansions. He saw a beautiful woman talking to her gardener out on the front lawn. Rehrig got out of his Ford Bronco, walked up to her, and asked if she knew of a place he could rent. Soon, the conversation got friendlier. She said her name was Sandra Bridewell.

It was another rapid courtship. Five months later, the two announced their engagement, and on December 8, 1984, they were married in a ceremony at the Mansion. Alan was 29; Sandra was 40.

• • •

Alan told his friends and his mother that he thought destiny had brought him to Sandra Bridewell’s front yard so soon after his arrival in Dallas. He felt some pity for Sandra and her two previous luckless marriages — his friends at Nowlin Mortgage say Sandra had given him the impression that her first husband had died of a brain aneurysm.

Alan adored Sandra’s three children; as the relationship began to develop, Sandra would have the two girls come up to his office on occasion and bring him a flower. Recalls Phil Askew, Rehrig’s boss at Nowlin Mortgage: “One of her daughters, Katherine, would say to Alan, ‘I’m pulling for you and Sandra. We need a daddy.’ It would make his heart melt.”

Sandra was the kind of sophisticated, chic woman that Alan had never known in Oklahoma. Of course, it took a while for him to get used to her style: his mouth fell open at a tailgating party before a TCU football game when Sandra refused to eat hot dogs; they were too messy. Occasionally, without giving Alan much notice, she would fly to New York to shop or discuss an off-Broadway play that she was partly financing. The play, ironically enough, was a dramatic version of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, in which the main character himself is a murder suspect.

“Alan would call me,” recalls Kirk Whitman, one of Alan’s friends from Oklahoma who also moved to Dallas, “and you could tell he loved this stuff. He’d say. ’God almighty, Sandra just showed up in a limousine.’”

But there was another side to Sandra that Alan also found attractive, one that her suspicious ex-friends tended to forget about too easily. She was considerate and giving. She got Alan and his co-workers tickets on the fifth row for a Bruce Springsteen concert, and she was generous with her fourth-row season tickets to the Dallas Mavericks home games. When the wife of one of Alan’s co-workers became ill, Sandra drove over and babysat with the woman’s young child. Recalls Alan’s mother, Gloria: “We were thrilled with Sandra because she seemed so willing to create a Christian marriage. We thought Alan would be the greatest opportunity in the world for her.”

But few of Rehrig’s friends thought the relationship would lead to marriage. “Sandra was sensuous and sexual, and Alan was handsome, tall, and a stud,” says Dean Castelhano, a co-worker at Nowlin. “We thought she was using him as a showpiece, putting him in a tuxedo and taking him to the Mansion. You know, it was exactly the same thing as the older guy who likes to have a young beauty on his arm.”

Ironically, Sandra’s friends were also worried about her new relationship. Some thought Alan was a male gold-digger. “No one knew anything about him,” says Barbara Crooks. “I’m not real sure he wasn’t after money, and he saw in Sandra a way to set himself up financially.”

“The marriage, you could say, for a young guy just starting out, would be a leg up for him,” says Carolyn Day. “I mean, doesn’t anyone think it odd that he showed up out of nowhere at her doorstep, and then he hotly pursued her? And Alan did go after her. Sandra used to tell me how he kept ’coincidentally’ running into her. One time she was at the New York airport with her children on her way back from Europe, and there stood Alan, who said he happened to be on his way home from a business trip.”

It was a relationship, then, that sprang from uncertain beginnings. It would end in Rehrig’s death, and Sandra Bridewell would no longer be merely an object of neighborhood whispers. She would be the target of a police investigation.

• • •

Phil Askew says he vividly remembers an emotional scene in which he and Alan were driving back from a Mavericks game in the fall of 1984. Alan, in tears, said that Sandra had told him she was pregnant. He didn’t know what to do. Says Askew, “Alan said to me, ’Sandra’s pressing for a wedding, and I need time.’”

When Barbara Crooks hears this story, she says, “That can’t be true. Sandra had a hysterectomy before she met Alan. She told me that she sat him down before they ever got married and told him she couldn’t have children. She felt it was important that he knew that.”

Obviously, somebody was lying, but Sandra and Alan quickly arranged the wedding. According to Askew, a few weeks after the wedding, Sandra called the Askew home from a 7-Eleven one night. Alan was at Askew’s house; they had once again been at a Mavericks game. Askew says that Sandra told them she was returning from Baylor Medical Center, where that very night she had miscarried. No one had been at the hospital with her.

Says Bill Dodd, “I don’t think Alan had any intentions of marrying her until he learned she was supposedly pregnant. Then he was committed to her.”

“Alan was a dip,” says Sandra’s friend, Suzanne Sweet. “He used that marriage for the social connections it gave him.”

Whatever the reasons for the wedding, within six months the marriage had turned sour. Sandra had sold her home on Lorraine, and they were living in a duplex on Asbury in University Park. One of Sandra’s neighbors there, who had become a close friend, remembers listening to Sandra complain that Alan had become a financial drain on her. Sandra didn’t understand why he was spending so much money. Meanwhile, Alan’s friends at Nowlin Mortgage watched in astonishment as Sandra ran up more than $20,000 on Alan’s American Express card. “He was really being pressured by American Express,” says Castelhano. “They were calling him two to three times a day. You know, he refused to ever ask Sandra about how much money she had. He never wanted her to think he was interested in her that way. But this, he couldn’t figure out.”

Sandra and Alan argued over how to treat Sandra’s son, Britt, who had been receiving bad grades at Highland Park High School and was often staying out late into the night. Alan found his prized golf clubs missing one day from his Bronco and blamed Sandra. He was furious that she hadn’t written notes thanking guests for the wedding gifts. Sandra told friends that Alan was no longer sexually interested in her. Alan’s mother says she even received a phone call from Sandra accusing Alan of having an affair. Alan called Ron Barnes, a lawyer friend of his in Oklahoma, and reportedly said. “I don’t know who I’m married to.”

On and on it went. A neighbor of Sandra’s says that in the summer of 1985, Sandra began talking about how she was worried that Alan might kill her. According to the neighbor, Sandra said she had hired the famed DeSoto private detective, Bill Dear, to check Alan out. Several of Sandra’s friends recall Sandra’s saying that Alan was into serious gambling, or maybe even drugs. Alan’s friends say such charges are ridiculous.

During the first week of November 1985, Alan and Sandra separated. Alan moved in with the Askews, who lived in Richardson. According to Barbara Crooks and Suzanne Sweet, Sandra began investigating the possibility of divorce. A neighbor remembers that Sandra showed her a bill for a $1,000 consultation with one of the city’s most prominent divorce lawyers. But Sandra never filed for divorce.

“Here’s something I’ll never forget,” says Kirk Whitman. “Alan and I were sitting in a bar after they had separated, and it looked like the split was permanent. And he told me that Sandra was frantic that, in the divorce, he was going to take half of what she had. All Alan said he wanted was the stereo and his camping equipment.”

On December 5, two days before Alan disappeared, Whitman says the two of them went to a Mavericks game, where Alan again brought up Sandra’s refusal to pay the American Express bill. “Alan turned to me and said. ’You know, tomorrow I’m going to try to run down some financial data on her.’”

If he did, no one knows what he found. The following Saturday, Alan was supposed to meet Sandra at a mini-warehouse in Garland to help her move a few boxes from the University Park duplex. Alan hadn’t seen her in a month, and Askew recalls that he was nervous about the meeting. The two men planned to meet later that evening for dinner. At around 4:50 p.m., Alan left to meet Sandra in Garland.

Alan Rehrig never came back. At 6:15 that evening, Sandra called Phil Askew to say that Alan did not come to the Garland warehouse. She added that it was just like him to miss an appointment. He had done this to her before.

Though Alan Rehrig didn’t show up Saturday night or Sunday, Sandra did not file a missing person’s report. When Alan did not appear for work on Monday, the executives at Nowlin knew something was terribly wrong; Alan never missed work. Still, Sandra wouldn’t file a missing person’s report. Askew himself filed one at 8 p.m. on Monday with the Dallas Police.

On an icy Wednesday evening two days later, two Oklahoma City police officers were cruising through a remote area in the city’s southwest side. They found a Ford Bronco with Texas license plates parked next to an electrical substation.

Inside, shot twice with a .38-caliber pistol, was the frozen body of Alan Rehrig. It was December 11, 1985, one year and three days after Alan and Sandra were married.

• • •

THE INVESTIGATION

“Sandra is sweet and wonderful, but, look, she’s a bit of an airhead. She’s not smart enough to mastermind a crime.”

–Suzanne Sweet

When the Oklahoma City police called Sandra, they were not able to notify her of Alan’s death. She asked, “Is it bad news?” When they said it was, Sandra did not ask what had happened. She only told them to call Alan’s friend in Oklahoma, Ron Barnes, and then she hung up.

Police say they were puzzled by her action, but they add that a grieving wife, suspecting the worst, might have wanted to hear the information from someone she might have known better.

When Barnes called her, Sandra became hysterical. Phil Askew went over to her home, where she wept throughout the night. The next day, a couple she knew from the Bobby Bridewell days came to see her. They both recall that Sandra, in tears, threw her arms around the husband and said, “No one is going to love me again.”

Another death. On the weekend of the funeral, Sandra looked devastated. Her behavior baffled friends as it had during Bobby Bridewell’s last days. She ordered the cheapest casket available for Alan; this infuriated his relatives, but she said Alan would have wanted it that way. Then, according to statements from Alan’s friends and relatives, she said she had forgotten to bring her checkbook and couldn’t pay for the funeral. Others had to take care of it. Nearly 400 people came to the funeral in Edmond. As far as anyone can tell, only one friend of Sandra’s came to Edmond — a University Park neighbor.

Sandra had talked to two Oklahoma City detectives the day before the funeral. They asked a lot of questions about her past. Had she told the Rehrig family that her first husband had died of a brain aneurysm, when he actually committed suicide? They wanted to talk to her and her children after the funeral. But, in another move that angered Alan’s relatives, Sandra left Oklahoma for Dallas hours after the service.

When the two detectives, Steve Pacheco and Ron Mitchell, came to Dallas that next week to look into the murder, they paid an unannounced visit to Sandra’s home. There they learned something that would change the entire nature of the investigation: Sandra said she had already hired an attorney, and that he advised her not to talk to the police. Nor would the children talk with them. When they asked if she would give them samples of her hair and fingerprints, she again said no.

Sandra’s attorney was none other than Vincent Perini, one of the most formidable criminal defense attorneys in Dallas. Perini wrote the Oklahoma City detectives a letter demanding that they never again try to talk to Sandra or her children. Perini also hired the private investigator Bill Dear to look into the case — Dear, the same investigator Sandra had talked with weeks before Alan’s death. Sandra told Dear that she believed Alan was associating with drug dealers and that she feared for her life.

In retrospect, some of her friends say that Perini came on too strong to the police, which made Sandra seem even more on the defensive. “In the ensuing months,” says Carolyn Day, “Sandra said she had stopped talking to him. She didn’t want him. She was trying to hide from him.” Perini will not comment on the case.

Meanwhile, the investigators were persistently retracing Sandra’s steps. They wanted to know exactly where Sandra was on the Saturday that Alan disappeared. The detectives had conflicting statements from Phil Askew and from Austin pediatrician Alan Franks and his wife, Barbara, two friends of Sandra’s who were visiting Dallas at the time. Askew told police that Sandra called him from the Garland mini-warehouse at 6:15. However, Barbara Franks said she called and talked to Sandra between 6 and 6:30 p.m. at Sandra’s home to firm up a dinner engagement that evening. The Austin couple told police that after dinner with Sandra that evening, the three went to see the movie White Nights. (A friend of Sandra’s recalls seeing the same movie with Sandra the evening before.) Police still are trying to verify Sandra’s precise whereabouts that Saturday night and following Sunday.

Only a few days after the officers’ visit to Dallas, according to confidential sources, Perini asked Sandra to submit to a polygraph test. She look one test on December 23 and another on December 30. A friend who went with her to the first examination says Sandra walked out of the polygraph examination office, teary-eyed, and said that she had failed two key questions.

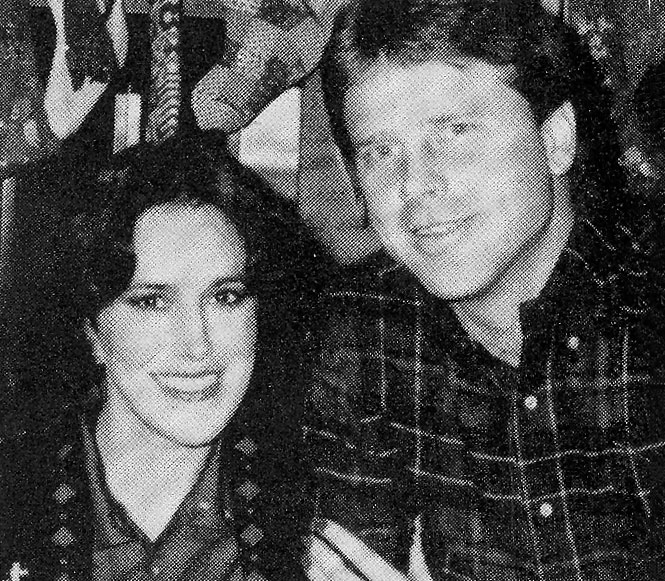

By the summer of 1986, someone else began to pressure Sandra — Alan’s mother. Gloria Rehrig, a high school counselor for 20 years, had rarely communicated with Sandra in the months since Alan’s death. Now Gloria was frustrated with the lack of progress in finding her son’s killer. In May, she came to Dallas to pass out leaflets in the Park Cities, bearing a picture of herself, Alan, and Sandra, and another picture of the Ford Bronco. The leaflet asked if anyone had seen Alan on the weekend he disappeared. Gloria says that when she went by Sandra’s home to ask for some of Alan’s personal items to keep as mementos, like his golf clubs and his Oklahoma State letter jacket, Sandra slammed the door in her face.

In July 1986, Gloria took her battle to court, and it was quite clear who the enemy was. In documents filed in Dallas County probate court, Gloria asked that Sandra be removed as administrator of Alan’s estate, saying that she was “suspected of having complicity” in Alan’s murder. Sandra was to be the primary beneficiary of $220,000 in insurance policies on Alan’s life, and Gloria didn’t want her to have them. By Texas law, a beneficiary of a life insurance policy can be denied the money only if he or she is convicted of murdering that person. If Sandra were indicted and convicted of Alan’s murder, Gloria would receive the money.

Gloria’s move was a long shot. No judge was going to remove a widow from an estate because of the allegations of a bereaved mother who stood to collect if the widow were discredited. Nevertheless, at an August 1986 hearing, Oklahoma detectives Pacheco and Mitchell were prepared to testify that Sandra was their suspect.

After some legal maneuvering, the hearing was postponed. Then, a month later, Sandra did something else that defied explanation: she suddenly resigned as administrator of Alan’s estate. Her attorney noted in a court document that she “has been subject to a series of accusations, which are both false and unfounded in fact.” The Rehrig family was ecstatic. Half of the insurance money was put into Alan’s estate (some of it used to pay the $32,000 in bills that Sandra and Alan owed); the other half will remain in escrow until questions about Alan’s murder are cleared up. Sandra has filed suit in California demanding that the money be given to her. A hearing is scheduled for later this year.

Sandra’s friends are livid about Gloria’s accusations. “Alan’s mother is simply trying to get financial gain out of this,” says Barbara Crooks. “The lady is money hungry.”

It is true that Gloria Rehrig is, as she puts it, “financially strapped.” She says she owes more than $20,000 in legal fees. But she maintains that justice is her real motive. A dedicated churchgoer, Mrs. Rehrig has created a sort of Christian network of friends to whom she regularly sends letters about the work being done to find Alan’s killer. “It is obvious from our trips to Dallas,” she writes in one letter, “that we are engaged in a very real spiritual battle.”

Meanwhile, the FBI continues its investigation of the murder. There is a question as to how much incriminating evidence was found inside the Bronco along with Rehrig’s body. Some hair and bits of fingernails were collected from the truck. And the trajectory of a bullet hole in the driver’s seat confirms that Rehrig was shot while sitting in the driver’s seat by someone sitting in the passenger’s seat. Hamburger wrappers were found in the truck, from which authorities have reportedly lifted fingerprints. Most important, autopsy results show some of the hamburger was still lodged in his throat when he was shot. It would appear that Rehrig knew his assailant well enough to be comfortable having dinner with the person. Since his body was discovered frozen, it is impossible for the medical examiner to pinpoint the precise time of his death. But an Oklahoma City private investigator has told police that while he was taking his girlfriend to the airport at 7:30 on Sunday morning, the day after Alan Rehrig disappeared in Dallas, he happened to see the Bronco by the electrical substation.

• • •

In California, Sandra Bridewell is trying to sever all her ties to Dallas. Although earlier this year her BMW was repossessed (a source says Sandra ran down the street after the tow truck driver), Sandra still has some money. She was able to pay off the loan to get her car back and also paid off a $60,000 loan she owed to the Bank of Dallas.

Her duplex on Asbury is for sale for $275,000. Even now, people driving down the street will slow down in front of the residence and stare. Vince Perini stopped representing Sandra in March 1986, but she has since hired another attorney in Dallas and also retains an attorney in San Francisco. Occasionally, her children call friends here. Her son, Britt, is attending a small college near San Francisco with a couple of his old Highland Park High School friends. “The kids went through everything that their mom went through,” says a Dallas teenage girl who remains best friends with Sandra’s daughter Katherine. “They heard all the rumors. They knew why other kids from Highland Park High School weren’t hanging around them any longer. I don’t blame them for moving to California. They felt deserted. You don’t know how those kids have suffered.”

Barbara Crooks says Sandra herself is calmer now that she has moved. “It was such a difficult situation with her former friends turning against her. She’s more subdued, but she hasn’t lost all her zest for living.”

It has been nearly a year and a half since Alan Rehrig was murdered, and although Lt. Robert Jones of the Oklahoma City Police says the case is under “vigorous, active investigation,” new leads to Rehrig’s killer seem as cold as that frigid December day when they found his body. Could it be that the beautiful Sandra Bridewell — despite her quirks and inconsistencies — is just an innocent, suffering victim of the worst kind of tragedy? Sandra’s close neighbor — a woman who was a confidante of Sandra’s all through the early days of the Rehrig investigation, and who now does not trust Sandra or speak to her — remembers going to a movie with Sandra one evening not long after Rehrig’s death. In the film was a scene where a man is suddenly shot.

“When it happened, Sandra leaped halfway out of her chair and almost fell onto the floor,” recalls the woman. “She was so startled. She had this sick look on her face. She got up and went into the women’s restroom and got sick. I looked at her, and I just didn”t know what to think. I just didn’t know.”

Authors

Eric Miller