The crossword puzzle printed in D Magazine’s debut issue was regrettable, to say the least. Unlike anything the average Dallasite had ever solved, it was full of trickery, wordplay, and—making it all the more impossible—British references. One clue: “Potter beside river for stickleback.” The answer: “Tiddler.”

The reward for the first person to send in a correct solution was $50, not a bad prize in 1974. But instead of getting a mailbox full of answers, the nascent publication got angry letters. Except for one. The sole envelope holding a correct solution was mailed in by a Highland Park housewife named Peggy Oglesby.

In fact, Peggy had warned the editors before they published that godforsaken puzzle. She had heard about the forthcoming city magazine from Jerrie Marcus Smith at a children’s birthday party. Jerrie was a board member and vociferous tub-thumper for D, a publication that her father, Stanley Marcus, helped by turning his Neiman Marcus customers into subscribers, and that she helped by giving it a name. (Dallas Magazine had already been claimed by the city’s chamber of commerce.) After that run-in, it occurred to Peggy that this new magazine might want a puzzle, but when she met with the editors, they informed her that a crossword had already been acquired from the London Times. “Oh no,” she said to them. “Nobody’s going to be able to solve that.” She had struggled with, and therefore delighted in, many a cryptic British-style crossword during a year spent abroad at Cambridge University, where she studied number theory.

Naturally, just as soon as Peggy pulled D’s first issue from the mail, she set to work. It took her six days to complete the crossword, including coming up with the British term for a small stickleback fish. Not only did the stay-at-home mother of two collect the prize money, she also won herself a side gig.

“I think that eventually I was paid something like $250 for each one,” says the 84-year-old Peggy, sitting at her dining table, still dressed for her morning workout in leggings, her white bob pulled back by a headband. “You can look around here and see what I did with it.”

She tips her head toward two large bookshelves. Every month, she took her D spoils straight to Aldredge Book Store on Maple Avenue, where she’d pick out a leather-bound edition of Middlemarch or Byron’s Life and Letters with goffered edges.

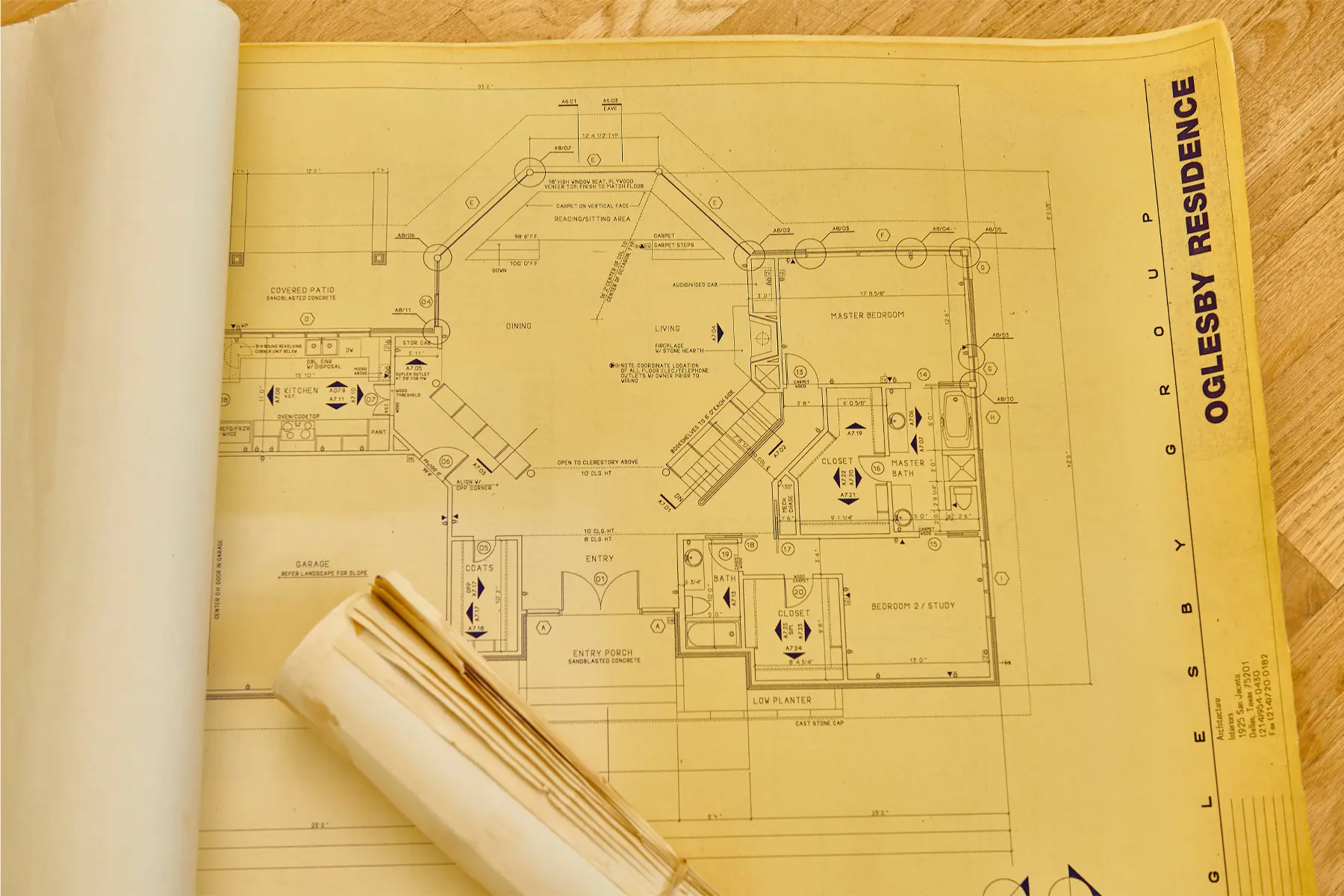

They are the first things I see when stepping into Peggy’s entryway: two double-sided bookshelves angled toward the door from opposite sides like arms held out for an embrace. Through the gap of the arms, Peggy leads me into her living space. There is a dining area to the left and a leather Vittorio Introini living set arranged in front of a fireplace to the right. Straight ahead is the main attraction, a lowered platform furnished with Eames chairs that looks through a trio of massive windows directly into treetops. Altogether, it is a glorious octagonal space designed to take full advantage of its site on the edge of a wooded creek.

Standing there, it strikes me as funny that I blew right past Peggy’s driveway at first. Just off a major thoroughfare in the heart of the city, the house is hidden at the end of a pea gravel road in the shade of a cedar elm. The structure is outwardly so unassuming but inwardly absolutely brilliant. A fitting puzzle of a house for the puzzle of a woman living in it.

I think that eventually I was paid something like $250 for each one. You can look around and see what I did with it.

Peggy wasn’t raised in Dallas, but the city may as well claim her. She was born here, and, when visiting from her hometown of Tulsa, it felt like coming home. “I thought I knew everybody in Dallas,” she says. Her great-grandparents were Rufus and Hattie Higginbotham, who moved from Dublin, Texas, to one of Swiss Avenue’s grand estates in 1913, prolifically augmenting the city’s population with 12 offspring. (Recently, Peggy and her husband sat down to dine at Suze and realized the table next to them contained some of her cousins, and one table down, another set of cousins, none having planned a family reunion.) Rufus proved to be a fruitful pillar of the city’s industry, as well. After starting out in dry goods, lumber, millinery, and peanuts, he became the director of the First National Bank of Dallas.

Peggy went east to Smith College for undergrad, though, at her mother’s behest, she decamped to SMU for her junior year to make her societal debut in Dallas. She returned to SMU after Smith to obtain her master’s in mathematics, then sailed across the Atlantic to Cambridge University. It was after that year of graduate work in number theory (“Just abstruse and wonderful,” she says) that Peggy’s romantic life began to heat up.

Calling it a love triangle might be bit dramatic, but it is true that the pairing of Bud Oglesby and Peggy was not as simple an addition as 1 plus 1. When Peggy left Cambridge, intending to help her ailing grandmother back in Dallas, she made the journey back on a ship. “I had had my car of all foolish things,” she says. After disembarking in Canada, she drove down the coast and stopped to stay with a cousin and her husband who were living in Watertown, Massachusetts.

The cousin threw a party, and among the crowd was a Harvard postdoc fellow named Richard Allison, who had recently returned from Vietnam. He was trim and tall with rust-colored hair. After talking most of the night, Peggy and this scholarly Army officer made plans for him to visit her a month later in Dallas. But almost as soon as Peggy arrived at her grandmother’s, she started dating a charismatic architect 15 years her senior with a well-established practice and Paul Newman eyes. And so, when Richard arrived in Dallas, Peggy explained that she was only available for two nights, as she had already committed to dates with her other paramour.

Peggy and Richard made the most of their dates, one of which was spent watching Ike and Tina Turner at Soul City, Angus Wynne Jr.’s new club on Greenville Avenue. But when Richard phoned Peggy from Massachusetts a few weeks later, she informed him that she was engaged. “I had to tell him this goose was cooked,” Peggy says.

The marriage announcement for Enslie “Bud” Orsen Oglesby Jr. and Margaret “Peggy” Ballentine Seay appeared in the Dallas Morning News on June 16, 1968, noting the bride’s “gown of silk organza with bodice of Belgian lace with seed pearl trim.” The newlyweds honeymooned across Russia and then Scandinavia, where Bud spent time after graduate school. Peggy had been working as a systems engineer at IBM up until her wedding, but when her boss declined to hold her position for the six-week trip, her life in the traditional workforce came to an end.

That was not the end of Peggy’s ambitions, however. She took flight lessons until the aircraft’s seat harness challenged her expectant midsection. And she began investing and managing the family finances just as soon as she had family and finances. “Peggy was the smartest person in our investment club,” says her friend Emy Lou Baldridge. “The rest of us didn’t know what she was talking about most of the time.” (Baldridge, herself, is no slouch; the wife of business magnate Jerry Baldridge, she founded Community Partners of Dallas, the advocacy group that helps 20,000 abused and neglected children each year.) While raising her boys and in the years to follow, Peggy would serve on various boards: Child Care Dallas, The Science Place, The Perot Museum of Nature and Science, and the locally based venture capital firm Remeditex.

In 1981, Peggy served as Junior League president, brushing off any attempts to make her treasurer. “I wanted to be king if I was going to get hooked,” she says. In that role, she initiated the rezoning of a building that would become the organization’s headquarters, an assist that her successor, Lyda Hill, slam-dunked the following year.

A month before Peggy took the Junior League crown, Texas Monthly published a feature by Richard West titled “No Man’s Land,” which illuminated the “both soothing and stifling” existence of women inside the Highland Park bubble. Through the eyes of a Junior Leaguer called Ann, however, the article described one woman who defied the stereotype.

“[Ann] regards Peggy with respectful awe, as do many of her friends who make it a point to drop Peggy’s name in conversations as proof that they are serious, thoughtful people and that the listener isn’t dealing with just your basic, large-bore Highland Park flit,” West wrote. The paragraph goes on to mention Peggy’s education, her puzzlemaking, her work to build a neighborhood playground, and that she sent her son to St. Mark’s by way of a city bus, a use of public transport described as “unheard of.” The latter point did not appear to be accusatory but rather reinforced Peggy’s particular mystique. “It was really sort of strange,” Peggy says of her cameo in the article. “I mean, what are you gonna do?”

The occasional recognition for her puzzles was a more rewarding thrill. She recalls working the door at an event one evening when a guest, looking at her name tag, remarked, “Oh, you’re the one that does those puzzles!”

“I thought, this is what it’s like to be Elizabeth Taylor,” she says.

The demise of Peggy’s Puzzling page came in 1981 when her editor, David Bauer, was ushered away to help D co-founder Wick Allison start a sports magazine in New York. She believes her new editor couldn’t make sense of the puzzles, even if provided the answers. She continued on with Houston City Magazine for a few more years, but she has since remained only a consumer of puzzles—an avid one at that.

Nowadays, Peggy starts every morning with two to three hours at her desktop computer, toying with various puzzles before checking on the stock market. (For the curious: HASTE is her starting Wordle entry, and her investment strategy is to avoid companies carrying more than 40 percent debt.) And she always has a wooden jigsaw splayed on her dining table, the puzzle box image hidden away.

I was surprised when she casually mentioned the deeper significance of the space we were sitting in. Built several years after her first husband’s death, it was Bud Oglesby’s final design.

As I sit at this dining table, I find myself puzzling together the pieces of Peggy’s story. I didn’t need her smarts to snap a couple in place. It made sense that she would live in a breathtaking home after being married to a renowned architect. But I was surprised when she casually mentioned the deeper significance of the space we were sitting in. Built several years after her first husband’s death, it was Bud Oglesby’s final design.

Every workday at noon, Bud walked the few blocks from The Oglesby Group headquarters to the downtown YMCA for a workout. Upon his return, he told his secretary to hold all calls, and, for precisely one half hour, he lay in repose on a daybed in his doorless, glass-fronted office, eyes shut, arms crossed over his chest. Perhaps it was that daily ritual that gave him the energy to fulfill the role of rainmaker for more than 40 years, the gregarious charmer counterbalancing the reserved fortitude of senior partner Jim Wiley. Together, the men built a firm that won dozens of design awards and attracted ambitious young architects like honey.

Bud had studied architecture at MIT, one of two graduate programs (the other, Harvard) imparting the tenets of modernism to scores of architectural disciples who scattered across the country, transforming the landscape of midcentury America. Bud set up his own shop in 1950 when Dallas was a postwar boomtown thanks to new aircraft and auto plants. The city was expanding with ranch home-and hacienda-filled neighborhoods.

“Modernism was not in vogue at all, but there was a certain social group, folks around town, who were intrigued,” says Joe McCall, speaking of those early days. Once one of those hungry architects pursuing the firm in 1975, he retired two years ago from what is now Oglesby Greene Architecture. “Bud provided this new, exciting modernism,” he says. “But it wasn’t chest-beating, bombastic design like some might think.”

Bud’s “quiet American modernism” was no doubt shaped during a formative year after graduate school in Scandinavia. There, Bud studied under Alvar Aalto, the modernist pioneer who softened the movement’s hard edges with an easy-flowing, organic sensibility.

That Bud’s designs slid into the North Texas panorama without disturbance was due in large part to siting. Bud often sought out interesting locations, designing structures to accommodate and even accentuate, say, a terrain’s gentle slope. “Let’s say there was a particularly charismatic tree on a site,” says Max Levy, who sharpened his drafting pencil at the Oglesby Group from 1977 to 1984. “Bud would design the building toward the tree. The view from the house would be framed in some compelling way that would bring out the soul of that tree. What made his work warmer is he related to nature in this silent, unspoken way.”

Levy says that when you combine attention to siting with a keen sense of proportion, the use of natural materials, and a muted color palette, “what you wind up with is something like easygoing jazz. His work was so suave, sort of like him.”

Yet this being a city that reveres novelty over history means that in recent decades, Dallasites have been knocking down Bud Oglesby homes like little boys plinking tin cans. “It’s just tragic,” Levy says.

Peggy, however, does not appear to be tortured by the gradual erasure of her late husband’s monuments. “The house belongs to somebody else,” she says when I ask her about the 2015 brouhaha over the demolition of a Strait Lane gem. “And a beautiful lady 50 years on is no longer a beautiful lady.”

In four decades of architectural practice, Bud designed college campuses, tidy condominiums, corporate headquarters, and estates for billionaires. He and Peggy raised their boys in a home near the Highland Park fire station that he had renovated, in part, but Bud Oglesby had never built a Bud Oglesby for his family. In the late ’80s, he designed a home for John and Mary Jo Vaughn Rauscher, and he carved from their estate a narrow parcel of land for himself. Peggy says Bud had already started on his plans for the lot when he was diagnosed with stomach cancer, which had spread throughout his body. He began to design in earnest, attempting to beat his own incalculable deadline.

Thomas W. Taylor was shocked when Bud called him to his house and answered the door in a tattered robe, pockets full of pills, his usually sunny face set in a scowl. Thomas had been the structural engineer on Bud’s designs since the 1960s. He was still something of a greenhorn when the architect roped him into a John Murchison project, building up a quiet Colorado town called Vail. But that day, in 1992, Bud needed help with the living room for his dream home. He wanted a raked ceiling but one that was interesting and aesthetically pleasing—basic sheetrock wouldn’t do. When Thomas returned with a model, Bud peered inside to see a truss system strung together with exposed cables. For a moment, the clouds lifted and Bud broke into a smile. “I knew you could do it,” Bud said.

“He knew that he was dying, and he knew he wouldn’t ever live in it,” Taylor says. “But he wanted so bad to build it for Peggy.”

And so when Bud died, in 1993, he left Peggy with plans to live. There was a space where she could showcase her prized books, a light-filled living room where she could piece together her puzzles, and a perch where she could watch the beauty of the natural world, a narrow sliver of green cutting through the city.

“When you pull up, it hits you,” says Cliff Welch of Welch Architecture. “That’s what I tell people about Bud’s work all the time. It’s just the restraint that he had. But even if it was out on the street, you could drive by the project a hundred times and never notice them.”

Cliff was an intern when he was asked to help Bud with the plans for Peggy’s house. I asked him to walk the house with me to point out the subtleties I might be missing. He notes the octagonal shape, Thomas’ cable trusses, the use of round columns between the windows “that tend to disappear more than something that is square,” and the importance of the living room’s lowered platform. “It gives this an intimacy that it wouldn’t have if it were on the same plane,” he says.

From their observation tower, Peggy and her second husband, Richard, occasionally see coyotes, white herons, eagles, and, of course, plenty of smaller birds flitting through the treetops. “We did have a high point of our observation of animals,” Richard says. “We had two bobcats copulating in our driveway.”

Peggy walks me and Cliff into her office to show us a binder holding photocopies of all her D Magazine puzzles. Richard shuffles into the office through the bathroom that adjoins to the main bedroom. He smiles politely as he watches Peggy. He has likely shrunk an inch or two, as old men do, but I can imagine him the trim, studious officer that Peggy went on 2 1/2 dates with in 1967.

After their Ike and Tina rendezvous, Richard returned to Harvard and eventually crisscrossed the States through a career in local, state, and then federal government. Peggy had all but forgotten Richard until cousins reconnected them after she was widowed. The two built Bud’s final house together and moved in the day it was completed in 1997.

As his wife searches the pages of her binder, I ask Richard if he has ever tried solving one of Peggy’s puzzles. He shakes his head and mouths the word “no.” Then he lifts his hand in Peggy’s direction and says, “I’m still solving her.”

This story originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine with the headline “The Unsolvable Peggy Oglesby Allison.” Write to holland@dmagazine.com.

Author