China Galland’s story “The Prisoner of Highland Park,” published in D Magazine’s November 1977 issue, tells the saga of the eccentric Mary Cosette Faust Newton and her adoring doctor husband, who built a $60,000 ship-like structure in their Highland Park backyard. (For the ship’s 1941 debut, Newton hosted a debutante ball, dressing up in a captain’s suit and presenting each deb with a white kitten.)

Galland was 16 years old when she was arrested for trespassing at the property, a crime that was practically a rite of passage for Dallas teens through the 1960s. Memories of that “house of horrors” came flooding back to her years later when she read a poem by Steven Orlen called “Abandoned Places.” By then, Galland was married with three kids and living on the West Coast, but her questions surrounding the strange residence and the rumored crime that occurred there called her back to Dallas.

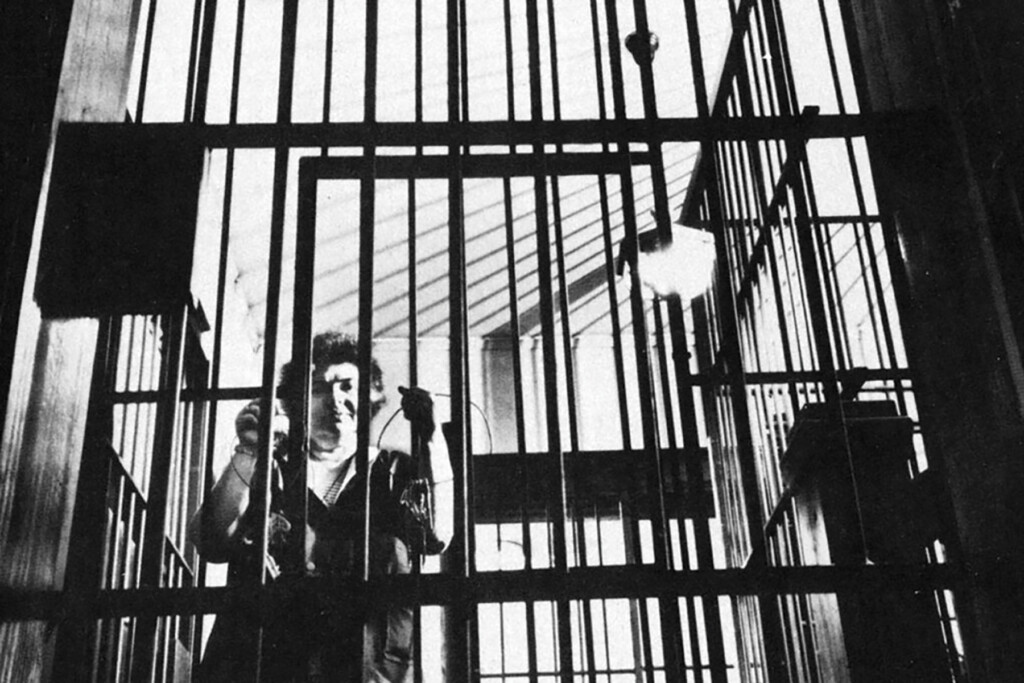

When the couple finally sold their barred, barricaded, and booby-trapped property in 1964, they put Newton’s treasures from her world travels on display for the public. The S.S. Miramar Museums, Galland noted, were “the medium of continual attempts to tell her side of the story and vindicate her name.” In some ways, the spin doctoring seems to have worked. There now exists a Facebook page dedicated to preserving the memory of the Newtons and the museum. Yet no posts on that page, nor any comments that I can find, directly mention the first incident that put the Newtons in the news: the kidnapping of Mickey Ricketts.

In July 1938, police received a tip that the Newtons’ former gardener, a 24-year-old Black man, was being held in their attic. Police found the young man severely malnourished, his face wrapped and taped in medical bandages, with a pair of handcuffs on the floor nearby. He had been kept in the attic for about a week, fed only a few hamburgers over the duration. Newton claimed that she had imprisoned Ricketts because he had stolen a jade ring that was given to her by a Chinese princess, the loss of which caused her “more pain than death.”

Newton, along with several of her employees and a private detective, were subsequently charged with kidnapping. Still, the police indulged Newton in a search for the ring. When a former maid was questioned, the woman said that she, too, had been accused of stealing the bauble some months earlier, and that, in fact, she was with Newton when she purchased the ring from a fortune teller for $1.49.

Ricketts sued Newton and her husband, along with seven others, for $57,300 in damages, and for weeks voluntarily remained in jail for his own protection. The Newtons ultimately paid Ricketts a settlement, and the young man promptly fled the state. The sum afforded his suffering: $500.

Neighborhood Spotlight

Dallas

In light of today’s known truths, Ricketts’ paltry recompense is not so surprising. While sifting through newspaper archives, I noticed that the judge presiding over Ricketts’ case against the Newtons was W.L. Thornton (brother to four-term Dallas mayor R.L. Thornton), a member and leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

Galland was unable to locate Ricketts during her research, but she discovered years later that he had died in the late ’70s in a southern California VA hospital. She says his treatment and the lack of justice has haunted her ever since she wrote the 1977 story.

“It illuminated something that I experienced growing up in Dallas,” Galland says. “I was going to Ursuline Academy, and the good nuns were teaching me we’re all the same. We’re all God’s children. I was growing up in a democracy, taking civics, learning about what an amazing country we have, where we’re all equal. Everybody can vote. Yet there were these contradictions. I remember asking my grandmother, ‘Why couldn’t Nash,’ who was her gardener, ‘come through the front door of the house?’ ”

Decades later, while visiting her family in East Texas, Galland once again encountered injustice when she met two women fighting to gain access to their enslaved ancestors’ graveyard, which had been behind locked gates since the 1960s. Galland wrote a book about the yearslong struggle to access Love Cemetery and then produced the 2023 documentary Resurrecting Love.

“This country isn’t real unless we live out the principles of our founding,” Galland says. “It’s all just talk, smoke, and mirrors if we don’t continue to work to create a society of liberty and justice for all.”

This story originally appeared in the June issue of D Magazine with the headline “House of Horrors.” It is one in a series of columns wherein the magazine revisits its archives to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Find more here. Write to holland@dmagazine.com.

Author