It takes Taylor Shead nine words to thread a connection between the scientific method and the entrepreneurial spirit. “In the sciences, everything is about having a hypothesis,” she says. She expands the connection into a web of parallels: although math is formulaic, science is about testing those hypotheses. As you gather findings and hone the hypothesis, she adds, you develop a theory. The entrepreneur’s process works the same way.

Shead has made her home within those parallels. As a child, the daughter of two entrepreneurs told everyone she wanted to be a reconstructive plastic surgeon. But by the time she went to Loyola Marymount University to play basketball, she found herself torn between majoring in business or natural sciences—ultimately landing on the latter. Today, she has built her career in the STEM education field, redefining what it means to get students engaged and on track for their careers with her edtech platform, Stemuli.

The journey between Shead’s beginnings and present is also strung together by a collection of hypotheses, studies, experiments, and tests. But it’s a journey that led to a clear result: Shead has mastered the art of not limiting herself. And along the way, she has removed limitations from the people around her.

Your Only Limit Is Your Creativity

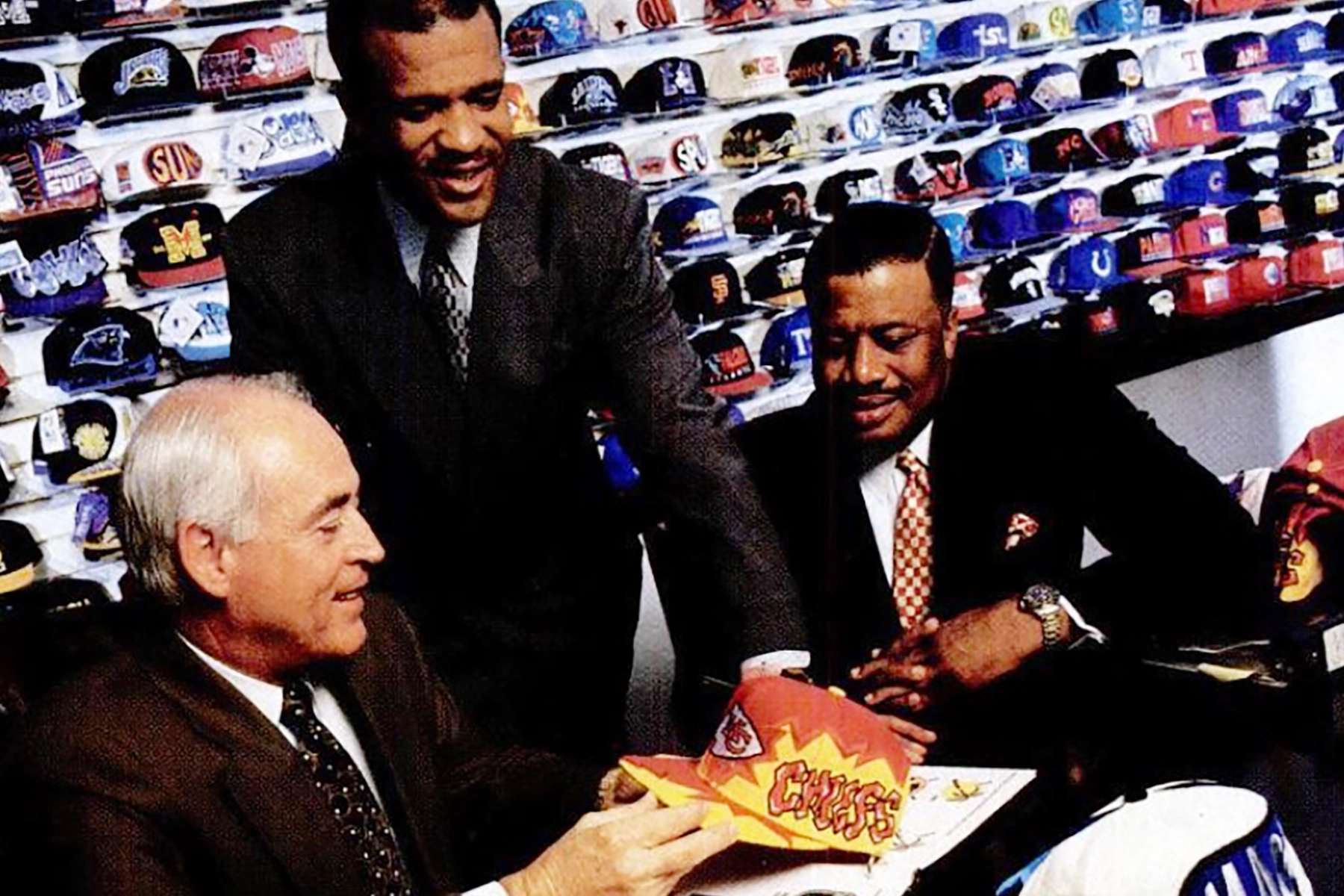

Shead describes the boardroom of her dad’s office in the context of hats. They were hung on the walls from floor to ceiling with a variety of logos. He worked in sports marketing and was one of the first Black retailers to win licensing deals from all major sports leagues. It was just one of many examples of creativity that Shead saw from her parents throughout her childhood.

After leaving her hometown of Plano for Loyola Marymount, Shead found the competitive environment in Los Angeles served as a haven for budding entrepreneurs. She also found that traveling as a Division I athlete presented its share of challenges. Just as she was having struggles accessing school materials while on the road, the iPhone was released. “If you can do all of these social things and other apps on your iPhone, why can’t you access everything from school on your iPhone?” Shead remembers thinking.

There were more realizations to come. After years of SAT prep and AP courses to prepare for a pre-med route, Shead was confronted by college chemistry; math wasn’t her forte, and she had a high school teacher who hadn’t effectively taught the concepts she needed to learn. Upon reflection, Shead saw in herself someone who grew up in the best schools in the state with dreams that were supported by her parents, yet she was someone who still wasn’t set up for success. If she was in this position, she wondered, what about the people she knew who didn’t have the best resources?

“I need to do something big enough so when people look at the life of Taylor Shead, they don’t see the failure of me losing my scholarship, they see more.”

Other pressures began to mount. Experiences with anxiety, the stresses of being a high-level athlete, and the feeling that she didn’t have the skills to continue down the career path she wanted twisted together and led to her skipping classes. “And there’s one thing that happens when you stop going to class,” Shead says, “you definitely fail that class—that is a guarantee.”

Shead remembers the moment her coach told her that her scholarship had been revoked. She remembers that she had options to play elsewhere. But merely playing somewhere else wasn’t the right thing to do, she believed. “I had the thought of, ‘I need to do something big enough so when people look back on the life of Taylor Shead, they don’t see the failure of me losing my scholarship, they see more,’” she says.

While in L.A., Shead surrounded herself with a group of older friends, many of whom were entrepreneurs who provided her with opportunities to grow. One, a software engineer who worked for Disney, fielded her questions about technology. “Finally, he told me: ‘Alright, Taylor, you’ve asked me the same question a million different ways. You can literally do anything you want with technology. Your only limitation is your creativity,’” Shead says. “That was the one quote or piece of advice that just changed my outlook on life. All of a sudden, I was living in a world with no limitations.”

Shead was also inspired by her own examples of this within the greater tech industry. Going into college, she convinced her mom she needed a MacBook computer. She heard the stories of tech innovators like Steve Jobs and those within Pixar Studios, who were continuously besting themselves as a key part of their trajectory. “Hey,” she thought, “you can develop products that are great, that people love, and that people want to stay devoted to for an entire lifetime.”

Plot Twists and Turns

On a late March afternoon, Shead is sipping from a glass of lemonade at Little Daisy on the ninth floor of the Thompson Dallas. Although her accolades and roles don’t begin to spell out her full impact in education and business, they provide hints: executive board member of Texoma Semiconductor, board member of the North Central Texas Economic Development District, and previous board member of the Dallas Education Foundation, to name a few. Quite a list for an entrepreneur who’s just 34 years old.

Initially, Shead was resistant to moving home. After withdrawing from Loyola Marymount her junior year, Shead was still living in L.A. She raised about $300,000 to start her first business—an educational tool that helped kids learn on the go and understand the importance of science and math in their future careers. Former Disney employees developed the minimum viable product (MVP) version, she says, and funds were raised through Greg Bestick of The Learning Co. and through a family friend and former PepsiCo executive.

At the time, tech had not yet caught up with her vision. However, the experience helped cultivate a knowledge through projects with the state of Utah, Pearson Education, and other clients. It also gave her experience in developing relationships and public speaking. Her dad encouraged her to move home, but Shead told him she liked L.A. She gave the same response to her grandmother. “My grandma said, ‘Taylor, I’m gonna pray about that.’ Thirty days later, I ended up moving home.”

After returning to Texas in 2013, she got a job with Apple. There, she learned about creating a finely tuned company culture. In June 2016, she filed paperwork to launch Stemuli as a business. Another wave of opportunity came that same year from Dallas ISD. The district was opening a Pathways to Technology Early College High School (P-TECH) program that connected industry partners with high school students, and they had noticed Shead’s tech-based education platform.

She began volunteering with the program and mentoring students during her lunch breaks at Apple, giving her a chance to give back and learn. “I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, this is what I knew needed to happen,’” Shead says. “Corporations need to be involved with this; they’re doing something right.’”

At the end of the first year, Shead asked students what their favorite field trip destination had been “And they said, ‘Miss Taylor, all we know is you and Stemuli.’ I was shocked by that,” she says. Looking into it, she found it came down to an accessibility issue. “Students didn’t have transportation to get out to the Microsofts of the world,” Shead explains. “So, we wanted to bring the world to the kids.” Stemuli began developing a platform to virtually connect students with mentors.

During her time at Apple, Shead met Wade Aston, a co-worker who was studying computer science at UT Dallas. After he graduated, he began working with Shead on her app. Today, Aston serves as the engineering manager.

Stemuli’s first product launched in 2018. The platform was adopted by DISD and eventually spread to Garland and Fort Worth, as well as some districts on the East Coast. By 2020, the platform was still in ‘chapter one’ of its existence, connecting students to mentors at Fortune 500 companies. Microsoft and Accenture employees were the first to use the platform.

And then, in the spring of 2020, Shead encountered a plot twist with the emergence of the pandemic. She worried that the students she met in 2016 through DISD’s P-TECH program, who were now seniors, wouldn’t be able to graduate if they couldn’t connect with their teachers. Fostering that connection became her new mission.

Shead and her team worked with the Dallas Education Foundation and DISD to create a virtual classroom on top of the existing platform. “We built that platform within three months,” Shead says. The product launched in June 2020. Although Shead had experience teaching kids about building resumes and interviewing with companies, developing the new product gave her a window into basic classes of the day. “Science and math class is just as boring as it was when I was in high school,” she says.

DISD leadership tasked Stemuli with building something the world had never seen before. A call from the district’s now current chief technology officer suggested that Shead gamify her platform. The Stemuli team began studying video games, taking notes on what made Roblox, Fortnite, Minecraft, The Sims, and other ames so successful. In August of 2021, Stemuli launched the country’s first educational metaverse that turned school into a video game. The move paved the way for an immersive gaming platform that took traditional school content and turned it into educational video-game quests. It could look like answering questions about physics concepts in order to help launch a rocket into space, or even playing racing games to answer questions about the Roman empire. The product allowed kids to choose an avatar. Unlike the Brady Bunch grid offered by Zoom, the Stemuli platform allowed students to see their teachers in a simulated classroom; they might see one of their friend’s avatars raise their hand if they had a question. If they wanted to emote, hearts appear over their heads.

Despite running into funding challenges, the team continued to enhance and support the product. Come May 2022, the company raised $3.25 million in funding, making Shead the 94th Black woman to ever raise more than $1 million in venture capital. Today, the Stemuli platform includes workforce development features like college and career readiness content, as well as agriculture and semiconductor content.

With the success of the product came feedback—students wanted to do more in the virtual world beyond a classroom. Teachers said kids were asking them for more homework so they could stay on the game. Parents loved that their kids had to be pulled away from learning to come to the dinner table but wanted to know what their kids were learning.

Based on that engagement, Stemuli acquired “GPS of Learning” tech to integrate into the game and provide analytics and data on student progress. Shead says Stemuli has launched the MVP of the next version, securing a deal valued at $15 million over the coming three years and an $8 million investment. Funds from that will be used to accelerate the next version of the platform, which personalizes curriculum for each student using their interests.

Shead says it’s about leveraging data for kids based on their interests. “Our view on data is different,” she says. “It’s like, ‘Who is this person? And how do you shape their entire learning experience around who they are?’”

From Gamers to Chip Makers

Shead is nowhere near finished crafting the future of Stemuli. Last year, the company celebrated a double merger with infinity.careers, founded by Naomi Thomas, and Oppti, founded by Khiry Kemp. Thomas now serves as Stemuli’s head of digital, while Kemp is the company’s head of operations. The three met through an entrepreneur residency program called Jobs for the Future. “My first impression of Taylor was that Stemuli was a much bigger company than the company I’d been working on,” Kemp says. “Her vision was bigger; she seemed to communicate on an inspiring-type level.”

Shead, Kemp, and Thomas gelled, so Shead suggested meeting in person. There, she pitched the idea of merging their companies; Kemp and Thomas agreed. “Taylor’s a big personality in all the right ways,” Kemp says. “I wanted to be in a position where I could be the lesser known, like Roy Disney to her Walt, as an example. I saw myself being the operations guy driving a lot of the execution while she’s continuing to up revenue and investments.”

Looking ahead, Stemuli is integrating generative AI into its platforms to build a never-ending video game and lifelong learning experience. The goal is enjoying a funding boost thanks to a grant from the Gates Foundation. Shead and Titilola Harley, program director of R&D K12 for the Gates Foundation, connected during a panel discussion in Washington, D.C. The foundation’s K12 education team focuses on improving math experiences for all students, especially Black and Latino students and students impacted by poverty, Harley says. At around the same time as the D.C. event, the K12 team was developing a cohort designed to connect ed tech developers who have math products that engage and motivate students.

As the team was building its cohort, Harley says, Stemuli kept coming to the surface. Not many math products are using augmented reality and virtual technology in the same way, she says. “They are constantly trying to make their product better,” Harley adds. “They do a lot of work to solicit feedback from students and teachers about all the elements that they’ve designed in the product so that all the design features are intentional.”

Stemuli is also poised to be a game-changer in developing the semiconductor workforce of the future. When it was announced that Southern Methodist University was designated as the lead agency for a federally funded economic development initiative focused on the semiconductor supply chain, Stemuli was added to the list of 41 members of the Texoma Semiconductor Hub.

“Stemuli is going to be the digital learning platform for that tech hub,” Shead says. “When people hear about the industry, they’re going to go to the Stemuli landing page and it is going to tell them how to navigate the resources in order to become prepared for jobs in this career.”

It’s a vision that Shead wraps up in a tagline: “Gamers to chip makers, chip makers to wealth makers.” A game within Stemuli will teach young kids how to develop chips, Shead says. She envisions Stemuli becoming a continuing education tool for students who graduate from high school but don’t immediately go to college. “As soon as they say, ‘I want to do something more,’ they have nowhere to go,” Shead says, “And sometimes they’re scared to step on a college campus. With our platform, they’ll have a compass.”

When Shead thinks about defining success, she’ll tell you it hasn’t yet been achieved. “When millions of kids are learning on our platform and getting great jobs, that’s what success means,” she says. “They’re on a career pathway. They’re not just learning math for the sake of it.”

Today, Stemuli boasts 100,000 learners. Shead says that will triple in the next school year. She has her sights on reaching 2 million.

For now, Shead says the infrastructure is in place for success. “We have the right people, we have the right partners, and we’re on to something with a product,” she says. “We’re doing what we can, but ultimate success is millions of learners having a different education experience than they have today.”

Author