When Melvin Ned Smith died at the age of 78 in April of this year, the future of the great Dallas institution he’d created was cast into a welter of recrimination and finger-pointing over his last will and testament. And then there was the matter of what would become of the Wall of Shame, a decades-old monument of broken tennis rackets, which we’ll eventually come to.

We are speaking, of course, about Milo Butterfingers, a bar that is far more than a bar. It is a temple of ramshackleness, open since 1971 and operating in its current location, a block from SMU, since 1982, a place where generations of men and women have met their spouses and where this writer himself many years ago earned a nickname for innocently dodging an altercation that involved his wife and a pitcher of beer. (It’s a long story, but the nickname is Mr. Breath of Fresh Air.) Milo’s also served as a setting in Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July, in which Tom Cruise, caroming between Milo’s pool tables in a wheelchair, drunkenly rants about the war in Vietnam. Call it one of Dallas’ finest dive bars, with a cinematic lineage that arguably elevates it above Adair’s Saloon, Ships Lounge, Louie’s, and whatever other joint you might feel nostalgic about, including One Nostalgia Tavern, and therefore be inclined to write a letter to the editor in defense of. (I support you.)

But back to Ned, as everyone who loved him called him. And there are many who loved him. Ned grew up in Fort Worth and did some rodeoing in Oklahoma and Arkansas, where a relative had a farm. He served in the Marines. He worked for Eastern Airlines at Love Field and eventually became a licensed sea captain. He favored Hawaiian shirts, was generous to a fault, and traveled every August to the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club, in California, to play the ponies.

Two quick stories about Ned: a man once tried to mug him in the parking lot at Del Mar. Ned was in his early 70s. His friends all say he was a gentle soul. Yet still he sent the thug to the hospital.

Years earlier—who can say precisely when?—Ned found himself one night at White Rock Lake with a couple whose company he’d grown weary of. They’d all been drinking. Ned decided to make his exit by swimming across the lake. Halfway through his journey, though, he realized it was a longer swim than he’d anticipated. He remembered his training in the Marines and fashioned a flotation device from his pants, which meant that when he emerged on the other side of the lake, where police summoned by the worried couple were waiting for him, he was pantsless. Or at least not wearing pants. Thankfully the cops knew Ned. They were regulars at Milo’s.

Ned’s obituary, unsurprisingly, did not include these stories. It said that he’d passed away peacefully in his sleep and that in 2007 he’d been preceded in death by his wife of 30 years, “the light of his life,” Jean Anne, who’d suffered a heart attack.

Which brings us to Ned’s will, executed in 2019. I heard the above stories from a lawyer named Randy Reed. After bequesting a couple hundred thousand dollars to friends and family, Ned split his residuary estate—not only Milo’s and the land it sat on but his $1.6 million house near SMU and other assets—between Randy and another lawyer named Ted Redington. Further, Randy was appointed executor of Ned’s estate.

I went to Randy’s duplex in Addison, where workers were busy remodeling in September, to talk to him about this sensitive matter. “Hell, no, I didn’t write the will,” Randy says in a Texan accent that sounds eerily like Nolan Ryan’s. “I didn’t know what was in it. I didn’t discuss with him his dispositive scheme. I was not present when he signed it. It was delivered to me after execution for safekeeping.”

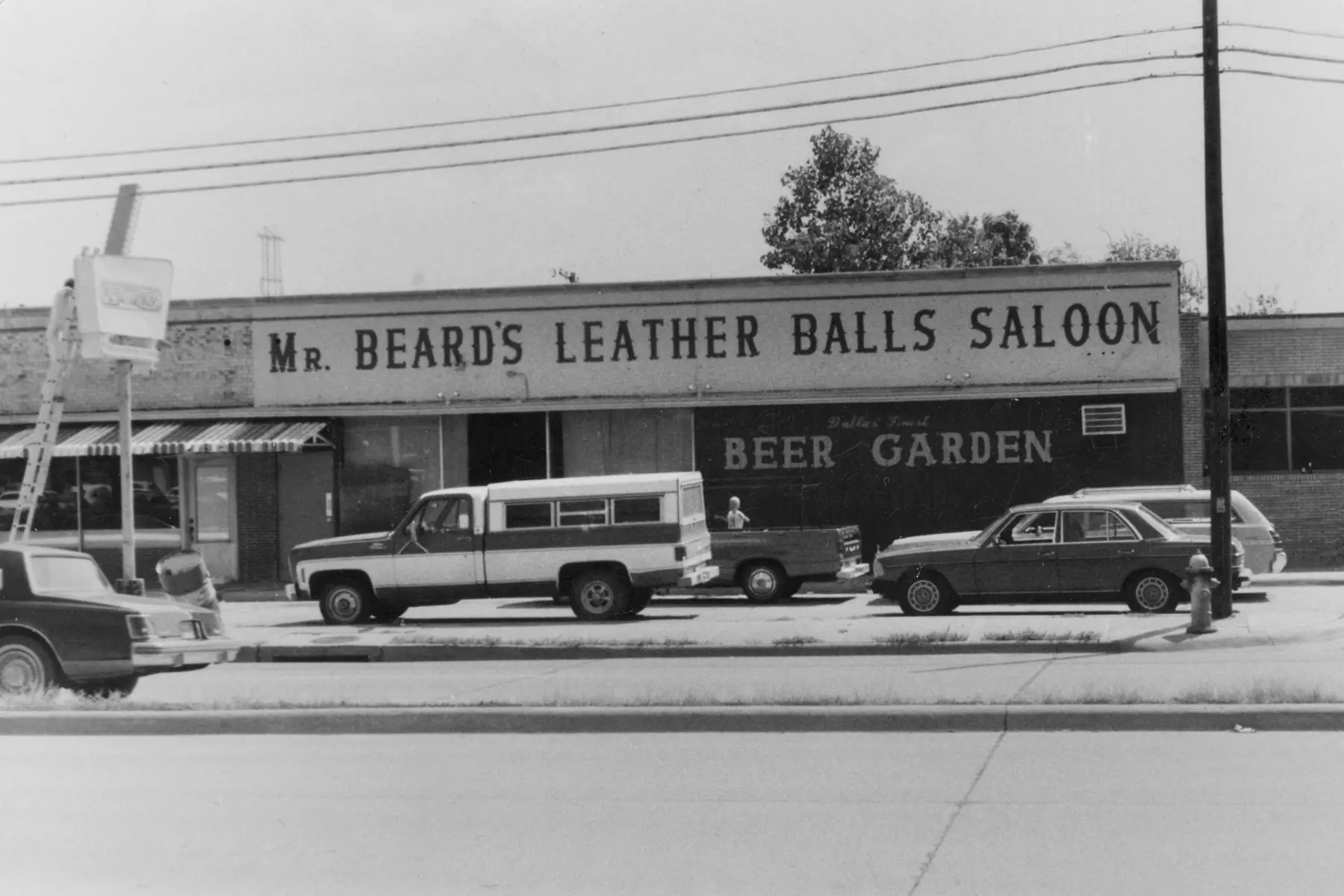

If that sounds like lawyerspeak, it is. For those unaware, it is illegal for a counselor to both draft a client’s will and be a beneficiary of it, unless that counselor is blood related to the client, which, in Ned’s case, Randy was not. Randy was related to Ned by horse racing and houseboats (they owned one together on Lake Grapevine) and, most importantly, bars. In the summer of 1976, before heading off to law school at St. Mary’s, in San Antonio, Randy worked as a bartender for Ned at Mr. Beard’s Leather Balls Saloon, a moniker Ned used for Milo’s during a six-year legal dispute over who owned the name Milo Butterfingers. (It was complicated.)

Two more quick stories about Ned: when Randy started at Leather Balls, Ned told him, “We’ve got rules about drinking behind the bar. There’s no drinking until midnight. Then you have to start drinking. Because these people are animals.”

There was a woman who drank at Leather Balls and routinely did so until she passed out and fell off her barstool. One night, Ned saw the woman on the floor, looked up at Randy, and declared, “Another satisfied customer!”

Things were different in the ’70s. In any case, Randy is steadfast with the following declaration: “Barry doesn’t know shit.”

Barry is Barry Smith, Ned’s nephew, who lives here and says he was told his entire life that Milo’s would eventually be his place. Barry not only believes that Ned was “manipulated and coerced” into signing the will, but he says of Randy, “He’s kind of a small guy with Napoleon syndrome.” I should note that Ned’s will gave Barry $50,000.

Another recipient of that same bequest was Tommy Donahue, the one-legged man who is Milo’s general manager and worked for Ned for 37 years. Tommy lost his right leg in a hit-and-run in 1981 and now operates a fundraiser for the Dallas Amputee Network called Legapalooza, which has been held annually for 15 years in October at Milo’s, until this year, when it had to move across SMU Boulevard, to the Barley House, because Milo’s new owners closed the place for renovations.

Tommy is more sanguine than Barry about the disposition of Milo’s. Though, after choosing his words carefully, he does say, “I think Randy had quite a bit to do with what was put in the will by the attorney who drafted it. I know that Randy is smart enough as an attorney to know that he couldn’t have drafted it, legally. He either coached Ned on what to put in it or coached the other attorney.”

As I say, it’s a sensitive matter. A beloved man is dead. His residuary estate has been distributed. Ned himself told Tommy that he’d leave him a piece of Milo’s. I’ve heard that promise from not just Tommy but from a friend of Ned’s who was close enough to stay with him several times at Del Mar. But a promise doesn’t count if it’s not drafted and signed, and now Milo’s is owned by two men who are not Tommy and Barry.

Again, Tommy has things in perspective. “Like I keep saying,” he says, “I don’t have any ill will towards these guys. I tell my employees and regulars, ‘These aren’t the people to point the finger at.’ We all know who the Scrooge is in this play.”

Which is worse? Scrooge or Napoleon? I guess at least Scrooge comes around in the end. Either way, Randy takes it in the shorts in this story. As he himself says, “I’ve asked those people what Ned promised them. ‘He said he’d take care of us.’ And he did. ‘Why are you mad at me?’ ”

Tommy wouldn’t say he’s mad. But he was hurt. After the new owners of Milo’s took over in July, Tommy went to New Hampshire, taking a couple of weeks with family to read James Patterson novels and to try not to think about the place where he has worked for nearly four decades. But he couldn’t help himself. He checked in on cameras inside Milo’s and saw that some things in his office were being thrown out. He says he was told that he wouldn’t miss the stuff.

“It’s like your mom coming into your room after you’ve gone away to college,” Tommy says. “She throws away your baseball cards and says, ‘You didn’t need those.’ ‘Well, yeah, I kinda did.’ ”

Randy and Ted, the two beneficiaries of Ned’s will, kept the land that Milo’s sits on, but they leased the business itself for 20 years to Chris Camillo and Len Critcher, who together have owned Chelsea Corner for seven years. Len also owns Inwood Tavern, which he bought a decade ago and which bills itself as the oldest continuously operating bar in Dallas (since 1964). They have been friends since they were ostracized together at an eighth-grade Highland Park lunch table. They have each made fortunes by selling tech companies and investing, but they seem to know how to run a bar as important as Milo’s. In fact, they call themselves “preservationists.”

“This isn’t my bar,” Len says one early afternoon at Milo’s. “I’m a steward of this bar now. I don’t walk into Inwood Tavern and go, ‘I’m the fucking owner.’ Half the customers there don’t know who the hell I am. I don’t need them to feel that this is Len’s bar. I don’t get my jollies like that.”

Chris sits next to him. They both went to SMU, Chris majoring in finance and Len studying film. “Under the new economics,” Chris says, “this bar doesn’t work unless revenue goes up meaningfully.” He talks about “risk capital.” Len talks about “programming.” They both talk about how much they miss The Loon in its original location and how Milo’s has 40 years’ worth of deferred maintenance. They’re sinking somewhere around $1 million into new bathrooms and HVAC and a glycol system so that the beer will actually pour cold. Stuff like that. Yes, they have raised prices and replaced the frozen Sysco burger patties with fresh beef from 44 Farms. And at this writing, in early October, they’d just closed the bar for major renovations.

“We will promise Dallas one thing,” Chris says. “When you come back to Milo’s in six months, you are going to love it. You are going to re-fall in love with Milo’s.”

I’ve talked with several Milo’s employees, including some who left after the change in ownership. And I had dinner there with the Slackers, a group of guys who’ve been coming in every Tuesday night for 35 years. Those are their broken rackets hanging on a wall above the kitchen, reminders of lost tempers on tennis courts, and the Slackers talked about maybe having to find another bar if their Wall of Shame didn’t endure. The old employees, the old-timer customers—heck, even me—we’re all susceptible to worry about change. Change is scary. And it’s easier to be mad than it is to be scared.

But do you want to know a secret about Melvin Ned Smith? He didn’t die peacefully in his sleep, as his obituary attested. After Jean Anne died, Ned never recovered from his grief. She truly was the light of his life. The pandemic, too, took a toll on him, and he saw his two siblings going through debilitating illnesses. His mother had suffered through Alzheimer’s. “His greatest fear,” Randy says, “was losing his mind.”

On the surface, Ned was a lot like his bar. He was old but ebullient, a treasure to all who were lucky enough to call him a friend. But when no one could see him, Ned was a mess. He was depressed and needed help. “We all tried to get Ned out,” Tommy says. “We invited him to lunch. He would cancel the day of, over and over. It’s important to say that it was a mental health thing with Ned.”

And so it goes, if it’s not too far a stretch, with the bar he poured himself into. Behind the scenes, Milo’s had become a wreck and needed attention. “This is an extension of Ned,” says Chris, who for years paid Ned an annual visit, trying to talk him into selling the bar. “Part of the reason why I love this place so much is because of what he represented.”

I never met Ned. But talking to the people who for decades loved him and drank with him and cashed his checks, I think Ned represented a longing. He longed for a wild night out. He longed for a lost love. He longed for a purpose in life.

Here’s hoping the new owners of Milo Butterfingers find at least one of those things Ned was always in search of.

This story originally appeared in the November issue of D Magazine with the headline “The Old Man and His Dive Bar.” Write to timr@dmagazine.com.

Author