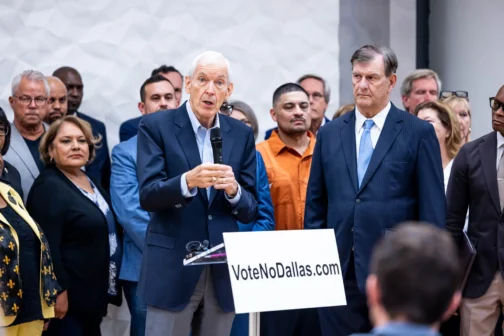

Representatives of Dallas’ past and present power structure stood shoulder to shoulder Wednesday in the basement of downtown’s Aloft hotel and may as well have declared war. The gathering of the city’s establishment—at least 45 people, including former mayors, a police chief, legislators, county commissioners, council members, a park board president, heads of (some) chambers of commerce and nonprofits and other assorted business interests—was a rushed show of force to convince the electorate to pay attention to something very few have: three changes to the city’s governing document, called the charter. Early voting begins in 18 days. Election Day is in 33.

“I know most of you are amazed,” said longtime Commissioner John Wiley Price, looking over his shoulder. “You never thought I’d be here with some of the people behind me.”

All of the current City Council was there, except for District 12’s Cara Mendelsohn and Mayor Eric Johnson. Former Mayor Ron Kirk said the charter amendments in question would be like “rolling a hand grenade into City Hall and destroying it.” Former Mayor Mike Rawlings called them “chocolate covered rat poison” that would “be the death of taxpayers and what they’re going to get out of the city.” State Sen. Royce West accused those behind the amendments of “using law enforcement as bait” to trick voters into saying yes.

What inspired such harsh language? The charter amendments were forced onto the ballot by an organization called Dallas HERO, which is largely made up of non-Dallas residents who solicited enough signatures from actual Dallas residents to present the three amendments to voters in the November election. The language of the amendments presents them as mechanisms to force the city to hire more police officers, fully fund the cop and firefighter pension, and hold elected officials to account. Those things will sound great to a lot of people. But Wednesday’s gathering asked voters to look deeper at their language to see what Price called the “collateral damage” they would cause the city.

Proposition S would force the city to waive its governmental immunity, freeing any resident or organization to sue if they believe a representative of the city violated the charter, any ordinance, or state law. Proposition T would require a randomized survey of 1,400 residents to determine whether the city manager gets a bonus or is fired, which is about one tenth of a single percentage point of the city’s 1.3 million population. Proposition U earmarks at least 50 percent of any new revenue—which includes property tax revenue, asset forfeiture, and a bevy of assorted fees and taxes—to go into the underfunded police and fire pension system and, upon the proposition’s passage, hire 900 officers to maintain a total of at least 4,000. (We presently have about 3,100.) The language does not account for increasing liabilities or obligations; it requires 50 percent off the top regardless of inflation or any other higher costs the city must deal with.

Dallas HERO was present for the event, too. Pete Marocco, the initiative’s executive director, stood in the lobby afterward talking to journalists and discrediting his opponents. “This is a group of, what, 170 grifters?” he told me. (There were no more than four dozen people facing the crowd.) “Many of them committed felonies when they came against us and abused public resources to do so,” he said. He did not elaborate, and nobody has been charged with any crime. “Our fundraising has never scaled up faster than after they saw Mike Rawlings making these statements,” he said. We were speaking no more than 15 minutes after the former mayor had finished his speech, and he was not quoted in a Dallas Morning News story on Tuesday afternoon that first noted his involvement. Marocco declined to say how much money the group has raised; it claims to be a 501(c)4, which is not legally required to divulge that. According to documentation provided by Marocco, the organization submitted its notice of intent to operate as a 501(c)4 to the IRS in August.

Wednesday’s public awareness campaign exemplified the Dallas political experience. The Dallas Citizens Council gets involved, a former mayor or two films a commercial, mailers get mailed. These campaigns are most often mobilized for matters like a bond that get tucked into sleepy local elections. Just 5.6 percent of Dallas County voters turned out for last year’s $1.25 billion bond election. Those types of campaigns have an almost singular goal: get enough people to vote.

This year’s matter is different. State law requires cities to conduct a review of their charters every 10 years. Most of the amendments that will appear on this year’s ballot went through a volunteer review board before being approved by the City Council. The petition-led effort from Dallas HERO bypassed this process. And the amendments get packaged on a ballot with a national election. Turnout will be far higher than in the city’s abysmal local elections; about 67 percent of Dallas County voters went to the polls in 2020. Many of those voters will not be familiar with what’s happening at City Hall.

“We have 30 days to defeat this,” said former Mayor Laura Miller after the event. “All the politicians did their job coming out today together. But if the business community of Dallas does not put the money in to counteract what Dallas HERO is doing, then we will lose. It takes money to win an election like this, because it’s very obscure. People have to understand what’s at stake.”

Many of Wednesday’s speakers recognized that the ballot language would appeal to the pro-cop populace. Who doesn’t want more officers? The speakers see their role as educating voters on what the propositions will actually do, which won’t be easy.

I spoke to former Mayor Tom Leppert and former Police Chief David Brown after the event about the difficulties in onboarding rookie officers—not even finding them to hire, just the logistics of training them.

“I want to be clear. I want more police officers. Our response rate is horrible,” Leppert said.

“That’s right,” Brown agreed.

“As soon as the number of police officers went down, our response times went down. It’s a one-and-one correlation,” Leppert said. “But it’s not just a question of money. I’ve gotta go higher [on salary]. Well, I think I can do that. But then you gotta put him through training. Well, I can do that. And here’s the real challenge. Once they get out of the academy, you’ve gotta have enough of the really skilled five- to 10-year officers, because that’s who they’re going to spend their first year with. As good as the academy can be, the reality of it is, their real training is that first year.”

“Field training,” Brown said.

“When you pull them out of the academy, you’ve gotta put them with someone,” Leppert continued.

“A veteran,” Brown said.

“Otherwise, you’re going to end up with a problem,” Leppert went on. “They’ll end up with a very bad experience. You’ll lose them to turnover. They’re not going to be trained enough. They’ll be in a bad situation. They very well could put citizens in danger. That’s the constraint.”

Point is, this is how complex the reality of the propositions are—and that’s before talking money. About 61 percent of the city’s nearly $5 billion budget is already allocated for public safety. The concern is that, should these amendments pass, the budget would tip toward police even further, forcing the city manager to cut services elsewhere, like road repair or libraries. As for the pension, the city already has a plan to bring it to solvency by spending $11.2 billion over the next 30 years. That plan is mandated to be turned over to the state’s pension review board, just four days before the election. Both Brown and outgoing Chief Eddie García say it would be virtually impossible to hire that many officers, much less train them. The city has already budgeted to add 250 officers, the most the academy can train in a year, but hiring has not outpaced attrition in the last decade. Interim City Manager Kim Tolbert estimates that it would cost at least $175 million to hire and train 900 new officers.

The City Council attempted to add three of its own amendments to the ballot that would effectively neuter the three from Dallas HERO, but that attempt was struck down as unconstitutional by the Texas Supreme Court. Which is why all these folks were in the basement of the Aloft hotel yesterday. At least two political action committees have been launched in the last week to raise money for a media blitz to counteract Dallas HERO’s outreach. Frank Mihalopoulos, a board member of the Dallas Citizens Council and the owner of Corinth Properties, says they have a goal of raising at least $800,000 to fund its campaign.

Rawlings began deputizing business leaders with organizing their industries: Gibson Dunn partner Rob Walters will handle the attorneys; Anne Motsenbocker, the former managing director of J.P. Morgan Chase, is charged with organizing the banks; United Way CEO Jennifer Sampson has the nonprofits; JLL CEO John Gates will be appealing to commercial real estate; former Park Board President Bobby Abtahi will advocate to parks and libraries; Young Women’s Prep Network CEO and philanthropist Lynn McBee has the arts.

“I’ve seen the pie chart for how Dallas HERO is going to spend their money,” Miller said. “They’re doing TV, they’re doing radio, they’re walking. They’re just doing everything, so we have to do everything, too.”

Although it hasn’t released any financial information, Dallas HERO is clearly well-funded. Canvassers fanned out across the city and got more than 169,000 residents to sign their petition. Monty Bennett, the wealthy hotelier and publisher of the Dallas Express, a partisan online publication, has told WFAA that he has offered cash and office space to the effort. His publication runs pro-HERO stories without disclosing any of his connections. Package all that with Marocco’s inflammatory statements and the Dallas establishment has a tough fight on its hands—and only a few weeks to win it. The forces behind Dallas HERO have been at work for months on social media and have already won a case before the state’s Supreme Court. How will the old ways of practicing Dallas politics—holding press conferences, getting editorials in the paper, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on paid media—fare when voters go the polls? We’ll find out November 5.

Author