In recent years, Dallas’ investment in greenspace has been more ambitious, targeted, and varied than ever before. Parks are no longer just major destinations and enormous investments. They’re on school playgrounds. They’re adjacent to greenbelts. They’ve replaced surface parking lots downtown and illegal dumps in South Oak Cliff. This park-building blitz has resulted in 74 percent of Dallas residents living within a 10-minute walk of some sort of greenspace, up from 60 percent in 2017. While this has been a collective effort from the city and a variety of nonprofits and other groups, perhaps no other organization has changed the calculus of how our city considers its greenspace more than the Trust for Public Land, which has named a new Dallas-based director for the state of Texas.

Molly Morgan has been with the organization since beginning as an intern in 2017. Nearly eight years later, she has accepted the top job and continued to juggle the organization’s projects of various scope and size. The landscape architect, who earned her master’s from the UT Arlington, has been integral in the Trust’s planning and community outreach, as well as using landscape architecture and design to meet the needs of the people who actually use these spaces.

“I feel such a strong connection to the communities that we serve that I felt like I wanted to ensure that we keep doing what we’re doing here in Dallas, building momentum, and taking all the great program work we’ve done so far and not only keep doing it, but expand it,” she says. “There’s many more people who need access, both in Dallas and across the state.”

She succeeds Robert Kent, who left the organization after a decade to become the chief philanthropy officer for the Communities Foundation of Texas. Kent was the face of the operation, one of the key figures in getting former Mayor Mike Rawlings to make an official commitment to invest in giving all Dallas residents access to a park within a 10-minute walk. Morgan has worked in nearly all aspects of the organization’s operation and prioritized community engagement.

“Molly is 100 percent dedicated to the notion that the Trust for Public Land is a vehicle for realizing the community’s hopes and dreams for parks and greenspaces,” Kent says. “That’s really one of her fortes, making the community feel welcome and understand that this is their park and we’re here to realize their dreams, not the other way around.”

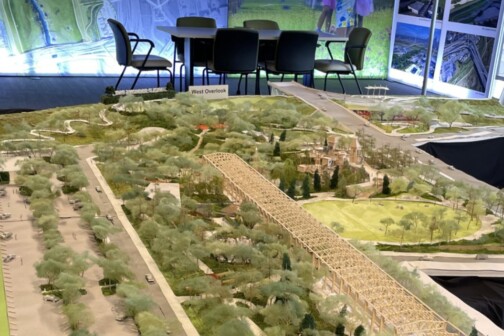

The Trust is managing an assortment of parks projects that all look quite different from one another. Mayor Eric Johnson charged the organization with identifying five locations for new parks on city-owned land. One of those parcels is just one-third of an acre, a small strip that will complement a planned library. (Ultimately, the Trust has a goal of turning 15 city lots into parks or greenspace, but just five are presently funded.) On the other end of the spectrum is Big Cedar Wilderness, a 282-acre property filled with walking and mountain biking trails that ascend to various overlooks facing north.

The Trust is also the lead designer and fundraiser for the Five Mile Creek trail project through Oak Cliff, which, upon its completion, will include three new parks and 17 miles of trails extending from the Westmoreland DART station into the Great Trinity Forest, where it will link up with the 50-mile Loop Trail. The organization has raised $44 million of its $78 million target for the project, which it hopes to complete by 2030.

Morgan’s master thesis at UTA was about what planner George Kessler envisioned for Dallas in the early 1900s, how nature and greenspace could connect people to civic institutions and amenities. Turtle Creek is the city’s success story for this type of planning, which Kessler also envisioned for other parts of the city that were never built. Five Mile was first floated as a possibility in the 1944 Bartholomew Plan, which saw greenspaces like it as nodes for economic development. Morgan and the Trust revisited that work and incorporated its ambitions into their design, working in tandem with residents from the community.

“People in southern Dallas along Five Mile Creek deserve access to nature that connects them to the rest of the city’s trail network, to an option of a safer route if they want to walk somewhere,” she says. “When we look at Turtle Creek today, it’s an amazing example of what benefit a place like that, or even the trail along White Rock Creek, can have in other parts of the city, too.”

Morgan wants to continue the momentum the organization has generated over the past decade. While it serves the entire state, the Dallas projects are further along in fundraising and planning—that’s the work Morgan has prioritized. And in a city where local government often finds private partners to perform work that benefits the public, the Trust for Public Land has established a model that’s showing real success balancing private donations with funding from local, state, and federal governments.

“There’s a place for the really big stuff like Big Cedar, which is critical to providing a certain aspect of nature to people,” Morgan says. “But there are places for you to just walk with your kid outside after school, where you don’t have to get in your car to get the benefit of being outside. I think looking at scales for how we can have opportunities for both and everything in the middle is going to make Dallas communities healthier and happier.”

Author