Fair Park’s privatization was sold as a way for the city to save tens of millions of dollars by allowing a for-profit operator to make use of its 34 buildings and 277 acres. Like all of Dallas’ public-private partnerships, the city signed a contract with a nonprofit, not the for-profit operator. That nonprofit, called Fair Park First, would be charged with fundraising for capital improvements and making sure their operating partner lived up to its end of the bargain. The city is basically the landlord and pays the operator an annual fee.

But Fair Park First did not exist until months before the city began considering the bid of that operator, Philadelphia-based Spectra. After the Dallas City Council approved the deal, in October 2018, the nonprofit overseer went seven months without a single employee. It had no money. At least three of its board members had financial or other agreements with the for-profit operator that required them to recuse themselves when considering a second management contract, board minutes show, which was the document that gave Spectra the power to operate Fair Park.

And now, according to an accounting report issued yesterday by Malnory, McNeal, & Co., $5.7 million has been misspent. Fair Park First and its operating partner are pointing fingers at each another.

If you want to understand the crux of this financial imbroglio, it lies with the very contract that privatized the park’s operation. Here is the language the operator, the Oak View Group (OVG), which bought Spectra in 2021, uses in response to yesterday’s accounting report of the mess: “OVG executed its responsibilities according to our contract.”

The contract it references does not include the city of Dallas, which is a different arrangement than exists in its public-private partnerships with entities such as the Dallas Zoo and the Arboretum. There are two contracts: One that the city signed with Fair Park First, and another sub-management contract Fair Park First signed with the for-profit operator, which is now known as OVG. Veletta Forsythe Lill, who assumed the role of chair in June after the resignation of its founding chair, says Fair Park First wasn’t built with the resources necessary to be an effective oversight body.

“Spectra thought we’d be little more than a marionette,” she told me. “And for five years, we pretty much were.”

The Dallas Morning News had a great rundown of the details a few months back. But the gist is this: the subcontract allows OVG to act as an agent “for and on behalf” of its nonprofit manager. Fair Park First has raised $17 million and has another $44 million in pledges, Lill says. The accounting report found that $11.3 million was deposited to a Bank of America account and “certain amounts” were then transferred to specified donor accounts. How those dollars would be spent is governed by agreements between Fair Park First and the donors; they aren’t meant to be spent on operating expenses.

Contractually, it seems no one knows where OVG ends and Fair Park First begins. Lill says OVG is contractually allowed to open and access bank accounts with Fair Park First’s name. “Everything has our name on it,” she says. “When funding comes in, the [donor] agreement is given to OVG.”

The accounting report indicates only that $5.7 million was misspent—someplace. The city is conducting its own full audit, which hasn’t been completed. Here’s a statement from Greg O’Dell, OVG’s president:

“Oak View Group is not responsible for any deficiency in the fundraising cash account balance at Fair Park. More importantly, the audit report confirms there has been no fraud or misuse of funds. OVG executed its responsibilities according to our contract. All fundraising cash was spent on Fair Park and Fair Park First exclusively, and all uses of donated funds were directed or approved by Fair Park First in writing. We have not received a demand from Fair Park First for payment of any amounts, but if received we will respond accordingly.”

After the release of the accounting report, OVG threatened to sue the audit company over language that alleged the entity “ultimately failed to comply with the requirements” set forth by the management agreement. Malnory, McNeal, & Co. then removed any language assigning blame. “This change seems to be a clear admission by the auditors that OVG was not at fault for any non-compliance with any provisions of the management agreement, and rather any failures are attributable to Fair Park First’s own actions and omissions,” read a statement from its general counsel.

So: we don’t know who is at fault. But we do know that the Dallas Park and Recreation Board, in August 2018, raised a whole lot of questions about the nature of this arrangement that left the city without oversight. Park Board Member Tim Dickey resurrected this discussion and brought up the questions during a meeting last month.

“The Park Board members at the time had questions that, in retrospect, are absolutely prophetic,” he said at the meeting.

“It all gets back to this structural flaw,” Dickey told me after the meeting. “You build on a bad foundation, and the building’s going to fall.”

That structural flaw, in his mind, is that the city isn’t a party to the contract that actually dictates operations and oversight. Fair Park First, try as it might, appears to have not had the resources or the contractual power to be a true oversight body. “There is no direct contractual relationship between the owner (City) and operator (OVG360), which is unusual and has proven to be highly problematic,” wrote Parks Director John Jenkins in a September memo to the mayor and City Council. “The consequence of this contractual structure is that we have very little ability to examine or oversee the entity that is actually operating the park on our behalf.”

In 2018, promises were made to the Park Board. Former Fair Park First Chair Darren James vowed to raise $3 million per year to offset operating costs. That hasn’t happened. The Park Board was supposed to be briefed on any capital expenditures over $250,000. Dickey says that has not happened. James also promised the Park Board they’d be able to review the sub-management contract before it was signed. That didn’t happen, either, and Fair Park First board meeting minutes show that the sub-management contract was actually approved by the board in August 2018, two full months before the Park Board OKed the privatization and sent it forward to the City Council. Those minutes show that the Fair Park First board was presented only with an “executive summary.” Lill says she does not recall ever seeing the full contract after that vote. The subcontract itself was signed by James and former Spectra GM Peter Sullivan in November 2018.

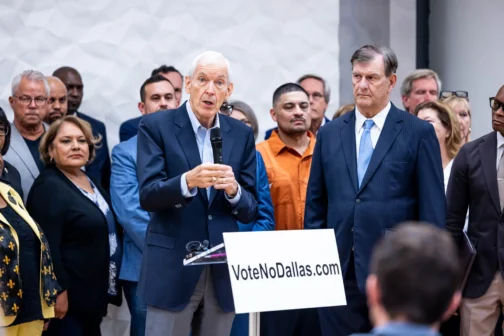

It’s important to remember how much of a powder keg this issue was in 2018. The city knew it needed to privatize Fair Park because it was losing its pants operating it. Mayor Mike Rawlings supported handing it over to former Hunt Oil CEO Walt Humann and his own nonprofit. Monte Anderson, the man responsible for the rebirth of the Belmont Hotel and Tyler Station, expressed interest. Councilmembers Scott Griggs and Philip Kingston pushed for a bidding process. The city attorney at the time, Larry Casto, said the interest from competing groups indeed forced the city to put the matter out to bid. In walked OVG (né Spectra) and a newly formed nonprofit, Fair Park First.

Going back through those meetings, James, Fair Park First’s founding chair, made assurances to Park Board that were never codified. Humann wanted $16.9 million to operate the park, and Anderson wanted $14.8 million. Spectra officials said they could do it for $35 million—total, over 10 years. The city was spending $15 million each year, so this immediately freed up $8 million to $10 million that it could divert into the general fund for other things. Spectra won.

Its officials talked an enormous game: they defended their low bid by saying they could make more money than the other groups by way of sponsorships and multiplying the events in the park, as well as the $3 million it planned to raise for operations. (Which, again, appears to have never happened.) At the time, the officials were self-assured, if not a bit cocky. At one point, Park Board Member Jesse Moreno asked about how Spectra could afford to bid so low. Here’s how David Leibowitz, Spectra’s vice president of finance, responded: “Maybe the easy way to answer that question is, well, there is a reason why you’re hiring us, right?”

But the foundation of this mess is in that subcontract between OVG and Fair Park First. It pushes the city out of the business of oversight, and it makes it difficult to untangle which of the entities at the park did what. In March, a whistleblower raised concerns of money moving around inappropriately. In April, Fair Park First reported it up to the city and launched an audit. Both sides denied wrongdoing, and then a rash of firings and resignations hit the nonprofit.

In any case, OVG knew it was facing a shortfall as early as January. Dickey recalled a one-on-one meeting he had with Michael Ahearn, OVG’s senior vice president for operations. The contract does have a clause that allows OVG to ask the city for money if it runs into financial problems. Ahearn told Dickey that the city’s response was “It’s not a good time.” A statement from O’Dell, OVG’s president of venue management: “OVG attended a meeting with Parks staff on January 24, 2024 in support of our client, Fair Park First, wherein Fair Park First laid out the park’s finances and requested additional funding. The discussion was positive, though no commitments were made.”

In support of our client. Fair Park First was presented to the public as an oversight body. Now? Good luck understanding who’s at fault or what happened. This is only bound to get uglier as the City Council, the Park Board, and the rebuilt Fair Park First board dig deeper. But the concerns raised in 2018 are bearing out today.

Author