Devo has always defied characterization within genres. Some stick it in the new wave aisle alongside Duran Duran, the B-52s, and the Talking Heads for its distinctive sound and aesthetic. Others stick it on the retail island with the punk albums made by the likes of The Ramones, The Misfits, and Black Flag, considering their antiauthoritarian ideas and cries for common sense in the midst of utter chaos.

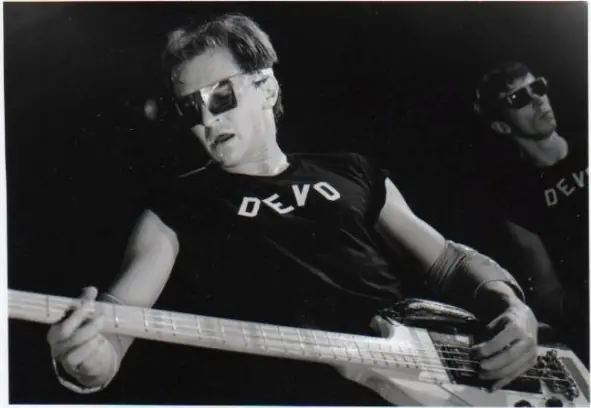

No matter how you classify them, Devo was miles ahead of its time when music needed a reboot. Creators Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerard Casale poured as much care and creativity into Devo’s visual aesthetic and spiritual ethos as they did for its sound, giving the world staples like “Whip It,” “Freedom of Choice” and “Girl U Want.”

“I think you don’t consciously say we need to do something new,” Casale says. “You are compelling to do something new and that’s what you are doing. That’s what happened from the beginning.”

Casale is being honored by Dallas VideoFest on Sunday, Sept. 29 at the Texas Theatre with the Ernie Kovacs Award, an annual recognition named after the television comedian who pushed the boundaries of the medium. It’s an honor that includes past honorees like Mystery Science Theater 3000 creator Joel Hodgson, Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam and John Cleese, Saturday Night Live and Late Night with Conan O’Brien writer Robert Smigel, and actress and humorist Amy Sedaris.

“There couldn’t be any Andy Kaufman without Ernie Kovacs. You couldn’t have Laugh-In,” Casale says, which is appropriate since Laugh-In’s creator George Schlatter is also a Kovacs award recipient. “He prefigured it all with these absurdist skits no one had done. He’s the only thing my parents could laugh at that I could also laugh at.”

Devo formed at Kent State University in 1970 in the shadow of the Ohio National Guard shooting that killed four students protesting the war in Vietnam. The following day, Mothersbaugh and Casale started batting around ideas based on what they saw as humanity’s de-evolution. Casale gives Mothersbaugh the credit for Devo’s foundation of using de-evolution as a form of artistic expression.

“When we connected and [Mothersbaugh] gave his big wrap of de-evolution, he was already there,” Casale says. “In tandem, we were both making what was Devo art. Sometime after that, I said ‘What would de-evolutionary music sound like?’ and that became like a class project. Let’s get together and experiment and that’s how we did it and rule number one was it can’t sound like other music.”

Casale says he was in a blues band at the time and Mothersbaugh was in a progressive rock band, so those genres canceled each other out. Instead, they decided to boil the sound down to its purest essence and make something new, the way a chef reduces a liquid to create a sauce that generates a rich, new flavor.

“Let’s do minimalism,” Casale says. “Let’s strip it all back and make it as primitive as we can. It was the whole ape/monkey brain thing that humans were twisted monkeys. We threw out anything that didn’t make us think or make us laugh.”

Devo also had to be completely different from the glitz and glam of 70s rock. Casale says it had to be something that refused to be defined by its own time.

“We knew what we didn’t want,” Casale says. “We knew what we didn’t like and we were trying to go beyond that. The good thing about Devo is why anyone would be talking about Devo at all? It isn’t because it sold 200 million albums like Elton John or The Beatles. It’s because the ideas and concepts that drove Devo and the structure of the songs and subject matter of the songs and the look of the videos and stage shows, so much of it transcended the test of time. We weren’t wearing white shirts with skinny ties and ripped jeans. We were doing stuff no one thought was cool and everyone was laughing at us.”

The group’s 1978 debut album Q: Are We Not Men? A: We are Devo!, a reference to the 1932 film Island of Lost Souls that was adapted from H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau. It features Mothersbaugh and Gerald along with brothers Bob and Alan Myers on drums. Devo’s aesthetic took the 50s view of what the future might look like in black and white toy commercials and turned it on its head with band uniforms that incorporated plastic hairpieces, loud hazmat suits, and round pyramid hats that became Devo’s iconic look known as “energy domes.”

Looks were just as important as the music. They invested heavily in video and film long before MTV made music videos a requirement for musical stardom. A film buff named Chuck Statler educated Casale on the ways of filmmaking. Statler is often credited as the godfather of the music video. He not only directed some of Devo’s seminal video works like “The Truth About De-Evolution” and “Jocko Homo” but also videos for Elvis Costello and The Attractions, Madness and The Cars.

“It’s an all encompassing idea, a fusion of music, video and political satire,” Casale says. “It was a big statement. It’s meta before there was the word. When we deconstructed [The Rolling Stones’] “Satisfaction,” we were taking one of the best rock songs in music and twisting it and taking it apart. When Mick Jagger sang about it, he was getting laid six times a day. When Devo did it, you believed we weren’t getting no satisfaction.”

The de-evolution concept even extended to the group’s instruments in order to produce Devo’s freakish, eclectic, and even sometimes silly sound, which bounced out in circuit-bent calculators, altered electronic instruments, and Minimoog synthesizers.

“We took instruments people did use and we completely inverted their use because when we were writing songs with the Minimoog, that was a big part of it,” Casale says. “Everyone was using the Minimoog to emulate strings and pretty things and we were using it to imitate white noise and industrial sounds. It’s all in the tradition of absurdism and dadaism when what appears to be nonsensical and stupid are these great, cool ideas and with humor.”

Devo continues to thrive after more than four decades of absurdist satire for lots of reasons. The biggest reason is unlike other musicians who long to make a statement or even satire with their songs, Devo never spoke down to its fans. Just like Kovacs did with his cartoony sketches that bended against reality instead of with it, Devo embraces silliness and absurdity on even levels over whatever’s perceived to be cool in its own time.

“Ernie [Kovacs] was obviously aware of the high art world doing this and putting it in these acceptable terms,” Casale says. “That’s very Devo.”

Author