Of all the movies shot in Dallas, Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise is the most singularly odd. Considering the existence of RoboCop, JFK, Logan’s Run, Office Space, and Mars Needs Women, that may seem like a bold statement. But if you’ve seen Phantom—a rock-and-roll black comedy horror riff on The Phantom of the Opera, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the legend of Faust shot mostly in the 1,704-seat Majestic Theatre—you’ll nod in agreement. (Those who know, know.) Then you’ll keep nodding and nodding until you’re bobbing your head in time to one of the incandescent songs burned into your memory by Paul Williams, Phantom’s songwriter and costar, whose performance as the film’s villain, Swan—a record producer who signed a pact with Satan, steals songs from a brilliant but unknown composer named Winslow (William Finley), and ruins the poor man’s life—represents the only instance in 1970s American cinema in which a 5-foot-2 actor can be said to loom.

The title character of Phantom is the alter ego Winslow creates in response to Swan’s cruelties. In prison, his teeth are extracted and replaced with metal implants. While trying to break into Swan’s record company, his face is disfigured and his vocal cords crushed in a record press. Then his soul is stolen by Swan by way of a contract signed in blood, and his voice is replaced with a distorted synthesized copy.

After stealing a black cape and a bird-beaked silver mask from Swan’s wardrobe department, Winslow makes like the more famous phantom, secretly living in the same theater made profitable by the theft of his art. He falls into unrequited love with Swan’s protégé, mistress and victim Phoenix (Jessica Harper), and wages war on Swan and his minions. The film’s final stretch is a Grand Guignol that fuses glam-rock set pieces to spectacular revenge killings meant to leave no doubt that there’s a true genius showman in the house.

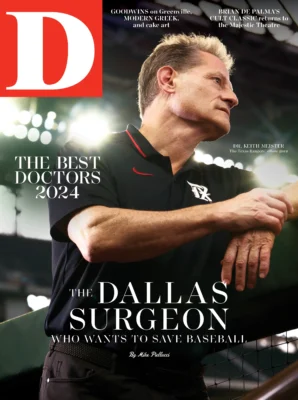

In an act of programming chutzpah worthy of Winslow, Phantom of the Paradise will be screened October 26 at the Majestic Theatre with Paul Williams in attendance. That means viewers will have the unique opportunity to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the film in the presence of the actor who plays the bad guy and watch the hero garrote, bludgeon, crush, stab, and electrocute his enemies on a 30-foot-high screen in the same venue where the movie was shot.

Phantom was born in a moment of Winslow-like righteousness. Sometime in 1969, De Palma was riding in an elevator when he heard a bland Muzak arrangement of the Beatles song “A Day in the Life.” “I thought, ‘Boy, they sure managed to take this really original song and turn it into pap!’ ” he says.

The incident sparked his imagination. He had recently been in England shooting footage for a documentary about rock-and-roll artists, including The Who, The Animals, and The Rolling Stones. “We were shooting them in all the original clubs where they’d played,” De Palma says, “and the producer [of the documentary] also knew Bob Dylan, so I’d spent some long evenings up where Dylan was, so I’d gotten to learn a bit about the music industry.”

By that point, De Palma had also spent a few years in the film business, which had its own parasites and predators. “I figured out pretty clearly what I wanted to do,” he says: a rock-and-roll horror film with original songs. Phantom’s antagonists would be the innocent and idealistic composer Winslow, whose Faustian rock-and-roll tragedy becomes a meta-commentary on the movie you’re watching, and Swan, who leeches Winslow’s gifts to ensure the success of the new concert hall he’s opening, then strips the composer of his art, his dignity, his face, his voice, his soul, and even his ability to die. (The contract signed in blood by Winslow specifies that he can’t die until Swan does; you can probably guess what the loophole is.)

Where Winslow is a pure spirit, Swan is the essence of corruption, Satan in polyester. The film’s opening narration is read by one of the devil’s most dedicated pop culture chroniclers, The Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling, in one of his last performances prior to his 1975 death:

“His past is a mystery, but his work is already a legend. He wrote and produced his first gold record at 14; in the years since then, he has won so many others that he once tried to deposit them in Fort Knox. He brought the blues to Britain. He brought Liverpool to America. He brought folk and rock together. His band, The Juicy Fruits, single-handedly gave birth to the nostalgia wave of the ’70s. Now he is looking for the new sound of the spheres to inaugurate his own Xanadu, his own Disneyland: the Paradise, the ultimate rock palace. This film is the story of that search, of that sound, of the man who made it, the girl who sang it—and the monster who stole it.”

De Palma filled out the screenplay with wild action scenes and outrageous supporting characters, including a fey, pill-popping Mick Jagger-prancing frontman named Beef (played by Gerrit Graham, with a singing voice dubbed by composer-performer Raymond Louis Kennedy); and a beautiful young singer called Phoenix (a then-unknown Harper, future star of Suspiria, Pennies From Heaven, and Love and Death).

Finley and Graham were known quantities to De Palma. He’d cast them in multiple earlier projects. Finley was in his 1963 short film Woton’s Wake, a precursor to Phantom about a sculptor who makes installations from garbage and steel and wears a mask and cloak so he can attack couples with a blowtorch.

“Because I knew what Gerrit and Bill could do, I got Gerrit to play Beef and Bill to play Winslow,” De Palma says. “But it took a little time to find Jessica. We auditioned a lot of girl singers.”

It came down to Harper and Linda Ronstadt, a respected singer-songwriter whose commercial breakthrough hadn’t happened yet (that would be the album Heart Like a Wheel, released in November 1974, after Phantom arrived in theaters). Harper did an acting audition for De Palma in New York, then was flown to Los Angeles to sing for Paul Williams.

By that point, Williams was already a worldwide superstar, thanks to writing or co-writing hit songs for Three Dog Night (“An Old Fashioned Love Song”), Helen Reddy (“You and Me Against the World”), and The Carpenters (“Rainy Days and Mondays,” “We’ve Only Just Begun”), and becoming a regular guest on talk and variety programs. Harper performed “Superstar,” a song that had been covered by the Carpenters but was composed by Leon Russell for the band Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, a major influence on Williams’ own sound.

“I tried to channel Karen Carpenter, who was sort of Paul’s muse then, in a way,” Harper says. “I was very nervous and pretty sure I wasn’t going to get the part, but I guess I sang and acted reasonably well.” That night, De Palma invited Harper to dinner at The Musso & Frank Grill in Hollywood. “A couple of people showed up to join us,” she says, “one of whom was this very jumpy young man named Martin Scorsese, a very good friend of Brian, and the other was the costume designer Rosanna Norton, who took me into the bathroom and measured every inch of my body, which I thought was either some really peculiar form of assault or a very good sign. I wasn’t sure which.”

It was the latter. “Linda could really sing,” De Palma says. “But so could Jessica, and that’s who we ended up going with.”

Harper says she would’ve wanted to be in Phantom no matter what, just for the chance to work with De Palma, a buzzed-about talent who hadn’t made it to the A-list yet. But De Palma’s original screenplay made her want the job even more. It was a unique blend of elements, including horror, melodrama, parody, showbiz satire, and a forward-looking take on American popular music. “Brian foresaw, I guess, the rock-and-roll future,” Harper says.

Williams loved it, too, but it was the more primordial elements that caught his fancy. “I like to say that Joseph Campbell should get a co-writer credit on this movie,” Williams says. “There are all these mythological, archetypal kinds of characters in Brian’s screenplay and references to all these other legendary stories.” Williams laughs as he recalls the moment soon after Phantom’s release when a couple of teenage girls recognized him in public. The girls excitedly asked if Williams devised the tagline on the film’s poster: “He Sold His Soul for Rock ’n’ Roll!” “I said, ‘Oh, no! As it says in the text of the film, and in the Faustian legend, “Well, there was this German guy.” ’ But I loved that. And I love that all these remarkable myths and legends and stories were heavily borrowed by Brian for the plotlines, from the Faustian elements to the Picture of Dorian Gray aspect. It’s just a remarkable film, and I was so honored to be part of it.”

TIME film critic Stephanie Zacharek favorably contrasts the movie to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which was released a year later and became a giant hit thanks to midnight shows with cosplay and call-and-response lines. “Without the audience participation factor—the chance to throw toilet paper at the screen, or whatever—there’s not much going on in The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” she says. “But Phantom of the Paradise is a movie you can actually watch, with an intricate story, extravagant musical numbers, and a great sense of controlled chaos—no audience participation necessary, besides simply entering its universe.”

De Palma had originally approached Williams only about writing songs for the movie, believing he was versatile enough to work in a variety of modes, from glam rock and acid rock to romantic ballads and retro-1950s bubblegum. (Williams calls the latter “the kind of Sha-Na-Na thing,” typified by the performance of a made-up band called The Juicy Fruits.) Williams wasn’t as confident in his composing range as De Palma was. “I wasn’t known for any kind of hardcore rock and roll, so I don’t know why Brian thought of me for that job. But I’m glad he did.”

He was gobsmacked when De Palma asked if he wanted to act as well. Williams had started out as an actor before turning to songwriting—he wrote his first song between takes while doing a small role in the Robert Redford-Marlon Brando movie The Chase—but there was nothing on his résumé to suggest he was lead role material.

“Brian’s first thought was, ‘Well, maybe you could play the Phantom, this little guy hiding in the rafters and throwing stuff down on people,’ ” Williams says, “and I went, ‘No, I could not!’ But then he suggested I play Swan, and I loved that and said yes, and all of a sudden I was in the midst of it. There were days when we were shooting when I’d film all day as Swan and then go directly to the studio and put vocals on some tracks, then go back the next morning and put fresh makeup on and start shooting again.”

Swan’s cult of personality was inspired by a visit De Palma made to the original Playboy Mansion in Chicago while reporting an article on Hugh Hefner. “When we went in there, in the middle of the day, everybody was sleeping, and we sort of looked around and said, ‘Where is everybody?’ And we figured out, Well, they’re all sleeping because the king of the place, Mr. Playboy, was sleeping. I’ve always been fascinated with the sorts of kings that control their environments that way. When Mr. Playboy, the king, woke up at midnight, that was daytime as far as he was concerned, so that’s when everybody else around him had to start their days. You see that kind of stuff a lot with megalomaniacs. Whether it’s Disney World or the Playboy environment, the environments are extensions of a particular man’s fantasies, so that’s what we did with Swan’s world. You’ll notice that all the doorways in Swan’s domain are just big enough for Paul, and everybody else has to duck to go in and out of a room.”

The Phantom shoot was funded independently by Gus Berne and producer Ed Pressman, son of Jack Pressman, a New York City-based toy manufacturer whose products included Disney tie-in merchandise. (The Pressman Toy Corporation was acquired by Goliath, which is headquartered, coincidentally, in Richardson.) Pressman would go on to become a major Hollywood player, working with the likes of Oliver Stone.

Phantom is set in an unspecified “big city” a la Metropolis or Gotham. “I don’t think we ever came out and named where it was,” De Palma says. Location shooting included a few days in greater New York City and Los Angeles, mainly at New York City Center on 55th Street in Manhattan (which doubled for the exterior of Swan’s Paradise Theater), Central Park (where Winslow climbs over a gate and runs into the park after escaping from prison), and Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills (the interior of Swan’s mansion, whose exterior was the Old Red Courthouse in downtown Dallas). The face-mashing was filmed in one of the Pressman Toy Corporation factories in Long Island, De Palma says. The bulk of the production happened in Dallas and Denton for six weeks in 1973 because Dallas crews were non-union, but also because the Majestic was the only theater in North America vast enough and old enough to provide the look and scale De Palma wanted, and that would let a film crew run rampant for 90 days.

In 1973, Dallas was known for just one thing—and it wasn’t the Ewing family of Southfork Ranch. “I’m of the generation that was quite young and very impressionable when John F. Kennedy was killed,” says Harper, who was 14 when shots rang out in Dealey Plaza. “I remember driving from the airport, and we passed the Grassy Knoll and the Book Depository, these iconic places in our past traumas, and it kind of gave me the shivers, honestly, and brought me back to that time. We all knew where we were standing and what we were thinking when we heard that news. So that was a little creepy. But maybe the creepiness was kind of suitable for the movie we were going to make.” The Majestic lived up to its name. “It had the same slightly haunted quality that it has in the film, so it felt like the right place to be.”

Pressman also rented a sound stage in Denton to construct some of the smaller sets, including Swan’s recording studio. Paul Hirsch says his editing suite was located “in one largeish room upstairs” from the soundstage. “I was working next door to the editor of a low-budget, locally produced film about a dog,” Hirsch says. “His cutting room was very messy, as if a bomb had gone off in mine. There were stacks of cans of film, pizza boxes, empty cans all over. I remember watching one day as he searched through endless close-ups of the dog, hoping to find a head turn. I felt very superior, being on a bigger production that was obviously much more professional.” The movie was Benji, and it would go on to be the most successful independent film in Dallas history.

Although De Palma had $1.3 million to work with—his biggest-ever budget—Phantom was still a scrappy independent film by Hollywood standards, and that meant everybody in the cast and crew had to pitch in and solve problems with imagination and elbow grease. For the scene where Beef is electrocuted by Winslow in the middle of a number, Hirsch “wanted to enhance the notion of electricity coursing through him [because] the production had used small sparks and smoke, but I felt it wasn’t enough.” He figured out that he could sell the idea of the character’s death by chopping up the frames and arranging them in a stutter-step pattern. Improvised solutions like that, Hirsch says, “are what has kept the film in the public eye for 50 years.”

The production designer on Phantom was a young man named Jack Fisk, fresh off another Pressman production, Badlands, the debut film by a then-unknown Terrence Malick. Badlands co-starred Fisk’s future wife, Sissy Spacek, but, because it hadn’t yet come out and put Spacek on the map, Spacek was working as Fisk’s assistant.

“Whenever we shot the sets they’d made, they were wet, because Jack and Sissy would spend all night painting them,” De Palma says. Though De Palma knew Spacek was an actress, “at that point I mainly knew Sissy as Jack’s girlfriend who was working in the art department with him.” That changed two years later when De Palma was in pre-production on Carrie and had “fixated on another actress” as a possible lead; Spacek boldly informed him that she should play Carrie White, gave up a New York commercial audition to screen test for the studio, “blew everybody away,” and won the part plus an Oscar nomination.

Pressman auctioned the finished Phantom to the highest bidder, 20th Century Fox. The studio scheduled its release for December 1974, then changed it to November to beat the announced release date of Tommy, Columbia Pictures’ rock opera (which ended up getting bumped to March 1975 anyway). “The unluckiest break came at the very end [of post-production], when we were hit by a number of infringement lawsuits and had to recut the picture with no time and limited means,” Hirsch says. One of the legal threats came from Swan Song Records, Led Zeppelin’s label, which claimed that the villain’s same-named record company would cause marketplace confusion.

“But that was a pretext,” says Ari Kahan, a Phantom aficionado who has been collecting memorabilia since age 12 and went on to found the Phantom-centric fan site Swan Song Archives, cheekily described as “the nonprofit wing of Swan Song Enterprises.” The real motivation, Kahan says, was that Led Zeppelin’s manager, Peter Grant, had learned that a film was about to be released that included a scene in which a musician was electrocuted on stage. Grant assumed it was making fun of the 1972 death of his friend Leslie “Les” Harvey, a guitarist for Stone the Crows, which toured with Zeppelin in its early days.

“Even though the scene had nothing to do with [Harvey], he swore to do everything he could to stop the release of the film,” Kahan says. Grant did not quash the film, and the electrocution stayed in. But he did cause Fox to send De Palma and Hirsch back into the editing room to delete any mention of Swan Song Records, even if it required visually ugly solutions (as in the airport Tarmac press conference introducing Beef, in which a Swan Song logo is covered up by its last-minute replacement, the Death Records logo of a deceased sparrow).

The other legal attack came from Universal Pictures, which had released multiple film adaptations of Gaston Leroux’s 1909 novel, The Phantom of the Opera: the silent version from 1925 with Lon Chaney, the 1943 sound version starring Claude Rains, and a 1962 version produced by Hammer. Universal threatened an infringement lawsuit against Fox for copying their intellectual property. There were no design elements in De Palma’s Phantom that were close to the Universal films, so the filmmakers believed the suit was groundless, but Fox settled it anyway for $500,000 that might otherwise have been spent on promotion.

De Palma is still bitter about that, in part because the conflict could have been resolved without fuss if Pressman hadn’t failed to pay the premiums for Errors and Omissions (or E&O) insurance, a common production safeguard against such situations. Kahan thinks the Led Zeppelin suit would’ve been resolved in Fox’s favor if it had gone to court because the fictional Swan Song Records in De Palma’s film was demonstrably not in the real-world music business. (The soundtrack, which was nominated for an Oscar and a Golden Globe, was released under the banner of A&M Records, Williams’ home label.) But he thinks Universal might’ve won because De Palma’s script had a plot element that was unique to Universal: Leroux’s novel doesn’t give many biographical details about the origin of the Phantom, but the 1943 and ’62 versions included a “stolen music” element for character motivation. “There’s no parody defense,” Kahan says, “because, while Phantom of the Paradise parodies many things, it’s not making fun of the underlying story—it’s an earnest retelling.”

A chopped version of Phantom was released November 1, 1974, to mostly positive reviews and a handful of full-throated champions, including The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael, an early De Palma booster, who said the filmmaker had “an original comic temperament; he’s drawn to rabid visual exaggeration and to sophisticated slapstick comedy.” But Phantom got stomped at the box office by other studio releases that fall, including Airport 1975, Earthquake, Murder on the Orient Express, and, as luck would have it, two more Lone Star productions, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Benji. (The latter earned multiples more than Phantom. “So much for feeling superior,” says Hirsch.)

An aura of failure cloaked Phantom for a quarter-century, even as it played regularly on premium cable; built unexpectedly intense fanbases in El Salvador, France, and Canada (where Winnipeg experimental filmmaker Guy Maddin fell in love with it); and wound up on VHS. Kahan blames the lack of TV ads in the United States, where the movie was mainly promoted with print and radio ads, “which was a problem because TV was the way to sell a movie like this, where the whole appeal is in how it looks.” He also thinks Fox’s TV ads were misleading because “they probably made the film come across as a movie by old people telling you that rock music was stupid, which wasn’t the case,” and that the film’s release was hurt by misconceptions about Williams, a lovable, diminutive pop icon (Hirsch compares him to Yoda) who hadn’t done anything that would have prepared viewers for the razor-blade edge he brought to Phantom.

Although Finley languished in horror and suspense projects for most of his career, he did four more De Palma films (Sister, The Fury, Dressed to Kill, and The Black Dahlia), grew his own devoted following, and got a New York Times obituary after his death in 2012 at 71. Other major participants went on to have notable careers. Fisk has been the production designer on more than 20 films, working with Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, Martin Scorsese, and Alejandro González Iñárritu. Spacek has won nearly every major award available to an actor, including an Oscar for Coal Miner’s Daughter. Hirsch edited or co-edited dozens more movies, won an Oscar as part of the editing team on the original Star Wars, and recently published a career memoir titled A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away. Harper acted in Love and Death, My Favorite Year, Minority Report, and both versions of Suspiria, and released books and music for children. Williams won a Grammy and a Golden Globe for writing “Evergreen” for the 1976 A Star Is Born, scored Alan Parker’s kid gangster fantasy Bugsy Malone, wrote the lyrics for the earworm theme to The Love Boat, and became a regular in the Jim Henson universe, guest-starring on the original The Muppet Show and writing songs for The Muppet Movie and The Muppet Christmas Carol. He is now president of ASCAP and a public advocate for sobriety, having been in recovery for alcohol and drugs since 1990.

The ’70s and ’80s were otherwise good to De Palma. He had an astonishing run of horror and suspense films starting with 1972’s Sisters and continuing through Carrie (1976), The Fury (1978), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), and Body Double (1984), with a brief hiccup of miscalculation (the 1986 mob comedy Wise Guys), then went to intersperse critical and box office hits (including The Untouchables, Carlito’s Way, and the original Mission: Impossible) with striking but divisive auteur statements (including Raising Cain, Snake Eyes, and Femme Fatale). Somehow, though, when the full arc of his career was discussed, Phantom tended to get left out. It almost seemed to have been omitted in discomfort, echoing the treatment of the title character in Leroux’s novel, a man hidden from society by his mother because of birth deformities.

But the movie’s energy and inventiveness ensured that it continued lurking in the shadows of culture, like Winslow in the wings. The 25th anniversary of Phantom inspired many reclamations and reconsiderations, most appearing in the then-newish arena of online film writing, which didn’t have to fight to justify precious column inches as in print publications. The renewed attention may have helped spur a 2001 DVD release, which was followed four years later by Phantompalooza, a Phantom-focused festival in Winnipeg that reunited Finley and Graham for a screening in the same local theater where Phantom debuted in 1974.

It was Phantompalooza that inspired Ari Kahan to start The Swan Archives; his obsession would ultimately lead to his participation in assembling a restored DCP of the film that incorporated previously cut material and interviewing De Palma for a deluxe 2014 Scream Factory release that included the excised “Swan Song” bits as supplements. French electronic music duo Daft Punk have cited Phantom as a formative influence; bandmembers Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter saw it 20 times in a theater during middle school, and they modeled the design of the main character in their 2006 film Electroma on Winslow’s Phantom. The movie has many accomplished fans, including Guillermo del Toro and Edgar Wright.

Kahan says the easier access of the streaming era might grow its fan base further. “The problem with Phantom wasn’t that people who might see it wouldn’t like it,” he says. “The problem was getting people to see it in the first place. Now that you can stream it, it makes it very easy to watch.”

“No wonder the members of Daft Punk saw it a gazillion times,” Zacharek says. “It’s a lot of fun, but there’s also something about it that strikes people deeply, which is why we still feel the tremors of its influence today.”

Williams thinks the film’s appeal goes beyond that. To him, Phantom is not just a musical or a ripping yarn; it’s a statement. “I remember that the first version of the script examined the music business, jumping off from Brian hearing the Beatles as elevator music,” Williams says, “but I think what evolved out of the process of making the movie was something about how we were at a place then when the line between entertainment and news was starting to disappear. I mean, we were sitting there in front of the television in America every night, eating our TV dinners and watching the latest footage from Vietnam, and then there would be a comedy or a variety show or something, and it almost felt like it all ran together.”

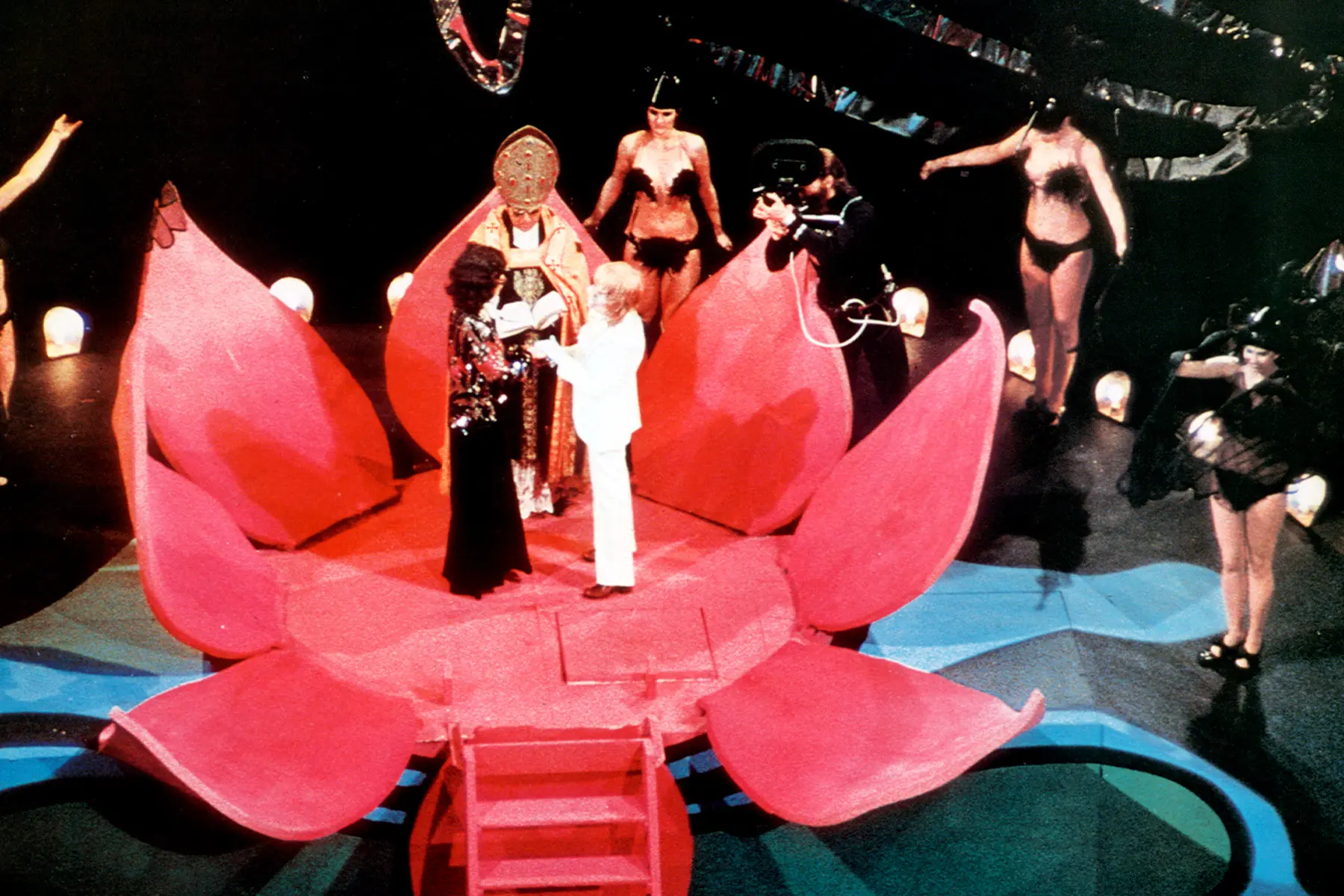

Williams cites a scene in Phantom that captured that aspect of the zeitgeist, when Swan decrees that a contrived entertainment event, loosely modeled on the 1969 wedding of singer Tiny Tim to his teenage fiancée Miss Vicki on The Tonight Show, would climax with an assassination. “Swan says, ‘An assassination live on television, coast to coast. That’s entertainment!’ I think that moment is the heart of the movie,” Williams says. “That’s what had happened to us in real life at that point, and you can still see it in what’s going on now, with our politics and a world that’s in crisis on a variety of levels. It’s something that I think is right there in the text of the picture. It’s kind of prophetic.”

This story originally appeared in the October issue of D Magazine with the headline “Phantom of the Paradise.” Write to feedback@dmagazine.com.