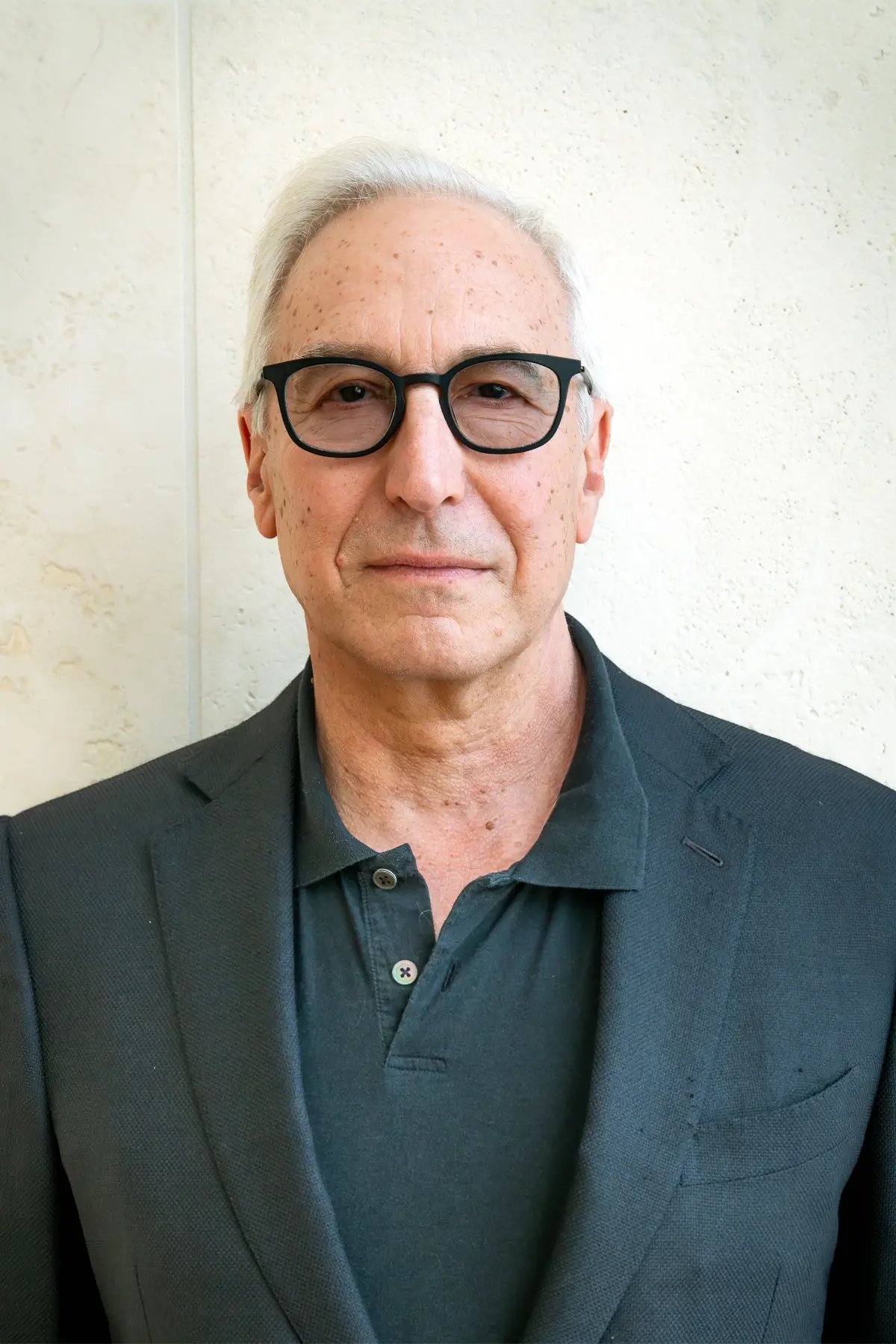

When Jeremy Strick assumed the directorship of the Nasher Sculpture Center in 2009, one of the first things he did was instruct his staff to compile a giant list of every artist and gallerist and arts writer in Dallas—be they brilliant or shite—and invite us all to an afternoon cocktail party on the lawn at the back of the museum. I had no idea who Strick was—that he’d directed the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and worked at the Art Institute of Chicago and the National Gallery of Art in D.C.—but the spirit of the event was precisely what hadn’t yet happened in Dallas.

I approached Jeremy after getting someone to point out to me who he was, and I thanked him for such a great gesture. I said, “No one has done this before here. This is utterly massive.” He said, “Yes, I know your work. I saw it at Anthony d’Offay in ’95. It was fantastic.”

(Jeremy’s favorite word is “fantastic.” It’s very positive, and he uses it a lot. For instance, the day I took him for a short ride in my new F-Type Jag, I redlined it in second gear on Exposition Avenue, and his response was: “Fantastic!” As I say, very positive.)

Finally, I thought, finally someone who’s not either totally medicated or totally committed to the philanthropist donors to the point where seeing the wood for the trees is reduced to a small park feature over Woodall Rodgers but someone who actually knows about art, culture, and history. Finally.

And this was the spirit in which he set about his next 15 years as director of the Nasher, until his retirement from that travertine temple in June. It will be a very hard act to follow. To place Jeremy’s contribution to Dallas on a cultural map, I’d use the following landmarks: Sir Nicholas Serota, the UK’s art world senior ambassador and architect of progressive change, and Jeremy King, possibly the greatest British restaurateur of recent times and a linchpin for London. I wish Jeremy Strick’s successor well, when one is chosen, but it won’t be the same. Times have changed, and the extent to which a museum director in such a role can be either reactive or proactive is a huge question. There is an overwhelming trend in global museum think—it’s a type of orthodoxy by now—and I’m not convinced it’s the best pathway. Dallas and Texas value their maverick trend-bucking values. “Saddle your own horse,” as Elaine Agather would say.

In time, Jeremy and I, sometimes alone, sometimes accompanied by others, took to walking the 9.4-mile perimeter of White Rock Lake on weekends. We’ve now done it more times than I can count, and we get to discuss many things. As a long-serving Program Advisory Committee member at the Nasher, I have found the lake’s shore to be a great venue for me to say the “advisory” things that possibly no one wants to hear and that can, in any case, only be said over 9.4 miles and would take up too much space in a meeting. Around the lake, there are no cameras or microphones. No one can hear you scream.

We discuss many things. It’s rare that we don’t touch on what I like to describe as Dallas’ Restaurant Paradox. Jeremy and I share a common love for the London restaurant St. John, a restaurant I used to live very close to and went to regularly, pretty much from the day it opened. What if we could magically transport the award-winning St. John to Dallas? Would it succeed? The answer is “No, it would not.” This is the Dallas Restaurant Paradox in a nutshell. It doesn’t have a restaurant the equal of St. John because St. John comes from, and is embedded in, a culture too different from Dallas. A great restaurant has many non-exportable moving parts—not least its own diners.

We didn’t talk only about dining and food, however. Many important and not so important topics have been covered. Some of them included such observations from me as “This collector is a plonker. What are they doing? What are they thinking? Do they actually know anything at all about art, a single shred of history or art history?” (I was asked to be as outspoken as possible when I joined the Program Advisory Committee. I learned quickly, however, not to make the same mistake Tugg Speedman made in Simple Jack. Their version of outspoken wasn’t the same as mine. I had to dial it back.)

My observations on our lake walks are often met with silence and the trademark Strick eye closing. I think anyone who knows Jeremy even only slightly will be aware that his thoughtfulness is matched by his precision. He chooses his words, often closing his eyes first as if to collate a philosophical overview with a kind of Rolodex of knowledge on many subjects. This might be anything from French philosophy to the authenticity (or otherwise) of the latest bagel place in Dallas.

At least with my “advisory” input, Jeremy had a way of agreeing while not entirely agreeing. Or not entirely agreeing but actually agreeing. His way of disagreeing was to pause and give a short mini lecture on the subject, as if it were unquestionable and irrefutably a statement of fact and circumstance.

An artist and old school friend of mine, Liam Gillick, called this “slippage” (now a technical philosophical term). Liam was tight with French museum director and curator Nicolas Bourriaud, he of the “altermodern” thesis, which in short is the theory that postmodernism is misnamed and is really just an extension of modernism. Slippage, to some extent, is the changing of words around for the sake of reclaiming power or asserting authority. Politicians have been doing this since time began. Liam would call it “a parallel universe, only now on a slight tangent.” Jeremy ultimately believes in the dissemination of authority, not in its capture.

These are the sort of erudite and closely nuanced lake discussions we have. And about bagels, of course. And about the best way to cook fish. Jeremy likes to steam or poach.

These are the sort of erudite and closely nuanced lake discussions we have. And about bagels, of course. And about the best way to cook fish. Jeremy likes to steam or poach. I tend to agree. My mum used to poach smoked haddock for my lunch when I was a preschooler, after walking to the village and back to the fishmonger, passing Donald Campbell’s land speed record-holding car called Bluebird. Anyone who knows me knows I can’t talk about smoked haddock, England, and Donald Campbell’s Bluebird as anything but one complete union of ideas, much like the United Kingdom itself. You can’t separate the component parts. But I digress.

At the same point in every walk, Jeremy will stop. It doesn’t matter whether the conversation is deep into parallel universes, slippage, poaching smoked haddock, or Mick Jagger—we both have stories about Mick—Jeremy will always stop on the footbridge near the dog park. He’ll then lean over the railing, and I learned that this is the one moment on the walk where it is prudent for me to halt the monologue/dialogue since no information will be received at this point. The watching of the dogs swimming in the lake requires Jeremy’s fullest of attention, and he kind of inwardly beams in an entirely dopey way. So do I.

Five minutes of dog-swimming-watching will ensue and then: “As I was saying, it wasn’t the first time I’d seen Jagger in public. He was standing right next to me, but what does one say? ‘You’re part of who I am, Mick’? ‘You formed the culture’? ‘The first chords on a guitar I ever played were from “Get Off of My Cloud” ’?”

There was a time in 2010-ish, after the mortgage crisis, when I was in what one today might call an income-challenged moment. I’d arranged with a decent collector who actually did know a bit about art to remake one of my large early paintings that had burned in the famous 2004 Momart warehouse fire in London. The original painting took me 14 weeks to make. Ten months into working on the new one, I was reliving all of the trapped memories that get locked into your brain when you focus on the same task for 10 hours a day with barely any break. The melancholy memories of the halcyon years of the mid-1990s haunted me for every working minute. Every three months there would be a polite inquiry from the collector asking how was it coming along? Was it anywhere near done yet? He was very patient, but it was a living hell because it was agreed my dealer couldn’t know about this project. So my dealer was also hassling me to make new work.

A week away from the painting being completed, the deadline had been set for it to be shipped to New York, the crate already built. The truck was due to arrive in a week. And so I decided to host a small party in the studio, a leaving party for the painting. I invited about 30 people, including Malcolm Warner, then curator at the Kimbell; philanthropist Nash Flores; arts writer Peter Simek; a bunch of artists and friends; and, of course, Jeremy.

Halfway through the painting, I’d come across the Depeche Mode video for “Personal Jesus,” a song about obsession. Seeing parallels with the protracted reproduction of a painting that had burned—the raising of the phoenix from the ashes, the resurrection—made me change the title of the painting from Motocrosser II to Your Own Personal Jesus.

Consequently, I decided to put a Bach cantata, “Ich Habe Genug”, on the stereo as the guests arrived. Ich habe genug translates roughly as “I have enough.” It’s the reconciliation, the coming to peace with the world and the desire to leave behind the toils of the material world into the arms of Jesus and everlasting spiritual peace. I’m not a devout person; I’m a secular humanist. And yet, in a sense, the painting was for me a type of deliverance. I’d resurrected my rite-of-passage painting, the very same painting I’d stood in front of at d’Offay with the God of painting, Gerhard Richter, with whom I was showing alongside in my debut show. (It was a giant Richter show. I was in the project room. It was like a proper martini. You show the vermouth to the glass, the rest is gin. I was the vermouth.)

Strick walked into my studio early. On hearing the Bach, he said, “Ich Habe Genug.” He knew it instantly. The recording was the famous 1950s Hans Hotter recording, the warmth of Hotter’s voice beautiful and manly all at once, in the way that 1940s Hollywood actors had a manliness that doesn’t exist anymore. Furthermore, it was one of about 20 unopened CDs that my music-buff father had left behind a decade earlier upon his premature death at age 69. My father had never gotten to hear it, even though he knew the work well. For my dad, it was art. It was the thing that would get him out of Newcastle, the thing that would elevate him above the streets where he’d grown up. His aspiration was toward culture, not money. By comparison, I’m the Champagne-swilling ne’er-do-well son, the flâneur.

Strick didn’t need any of this story. When I told him I’d retitled the painting, I could see his brain ticking away. He put the cantata and the title of the painting together very quickly. He simply got it. He already knew the painting. He’d seen the original one in London, way back in the day. In Jeremy and his family, I recognized something of my own parents and my own upbringing—something I’d been missing in my first five years in Dallas.

At the wonderful leaving party for Jeremy organized by Nasher exhibiting artist Piero Golia, there were llamas, a marching band, and Kilgore College Rangerettes, something so unfamiliar that I thought they were a type of art work by Golia, an utterly fantastic throwback to the 1940s. At last, some sanity was my thought as I walked up to one of a trio and told her I loved her outfit. She showed us to the garden, to the llamas and the oyster bar. It was a magical event, kind of A Midsummer Night’s Dream meets Lewis Carroll.

Jeremy and Wendy Strick stood for most of the evening in the middle of the garden, illuminated by a discrete spotlight to receive well-wishers. After consuming about two dozen oysters (some say oysters can make you drunk, and this might be true, but it was hard to tell after five glasses of Champagne), I made my way over, already elated by the llamas, the Rangerettes, the marching band, the large crowd of people, many of whom I realized I’d known for over 20 years. There were many artists, many gallery and museum people, collectors, benefactors. I knew I was going to get emotional. I mean, I’d been emotional all evening. I was emotional at the sight of the Rangerettes, to be totally frank—more so than at the sight of the llamas even. But as I stood back by 10 yards, respectfully waiting while Joyce Goss, a fellow Advisory Committee member, hugged and spoke with the Stricks, I saw that Goss cracked. Her eyes filled with tears. That’s when I got a lump in my throat and semi lost it. But I pulled it back and did that manly thing of setting my jaw, even though my eyes were beginning to glaze. Eventually, Jeremy was free for a moment, and I walked up to him, bookending that first time I’d met him, only 20 yards away on the steps. I had no idea what I was going to say, but then I totally lost it. My eyes flooded with tears worse than Goss’. I put my hands on Jeremy’s shoulders, and I couldn’t speak. Eventually I managed: “I have no words, Jeremy. I can’t speak.”

I turned somewhat abruptly away, trying to hold it together, and walked back toward the steps as if I had something important to do, but my shoulders shuddered for a moment, and I sobbed. I gathered myself. More oysters. The youthful but 1940s-ish Rangerettes somehow pointed the way forward.

Why was it so emotional, why so many gushing? I guess it felt like a fin-de-siècle moment. We are in a very different political universe. I have no idea what this means for art. All I knew was that a chapter had ended, and a new one must begin.

This story originally appeared in the October issue of D Magazine with the headline “The Art of the Real.” Write to feedback@dmagazine.com.