The Dallas City Council has now become the switchman and will decide how (and whether) a high-speed train will run from here to Fort Worth.

As expected, the entity responsible for planning a bullet train to Fort Worth unveiled Thursday an alternate route that lays tracks just west of downtown Dallas. The elevated rail line would run parallel to Riverfront Boulevard and cross the Houston and Jefferson Street viaducts as well as Interstate 30 on its way to a federally approved, seven-story-tall station in the Cedars. The route avoids existing and forthcoming downtown towers.

The Dallas City Council forced this alternative. Last month, the body unanimously approved a resolution opposing any above-ground rail lines through downtown in reaction to an alignment that wedged the seven-story tracks between the $3 billion convention center overhaul and the Hyatt Regency, near Reunion Tower. The resolution also triggered an economic development study of high-speed rail in Dallas, Fort Worth, and Arlington, which won’t be complete until at least 2025. Hunt Realty is planning a $5 billion mixed-use turnaround of a presently comatose 25 acres of southwest downtown across from the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center. Many councilmembers expressed concern about the impact an elevated train line would have on those plans; Hunt’s position is that a line through downtown would kill its plans.

The North Central Texas Council of Governments (COG) is planning the train route. Thursday’s presentation was the first time the agency framed the extension to Fort Worth as a critical hub for future high-speed rail access to other states. A line from Houston to Dallas is already federally cleared, and Amtrak has taken the reins. Michael Morris, the transportation director for the COG, said Amtrak has until the end of the year to add the bullet train to Houston to its long-term financial schedule.

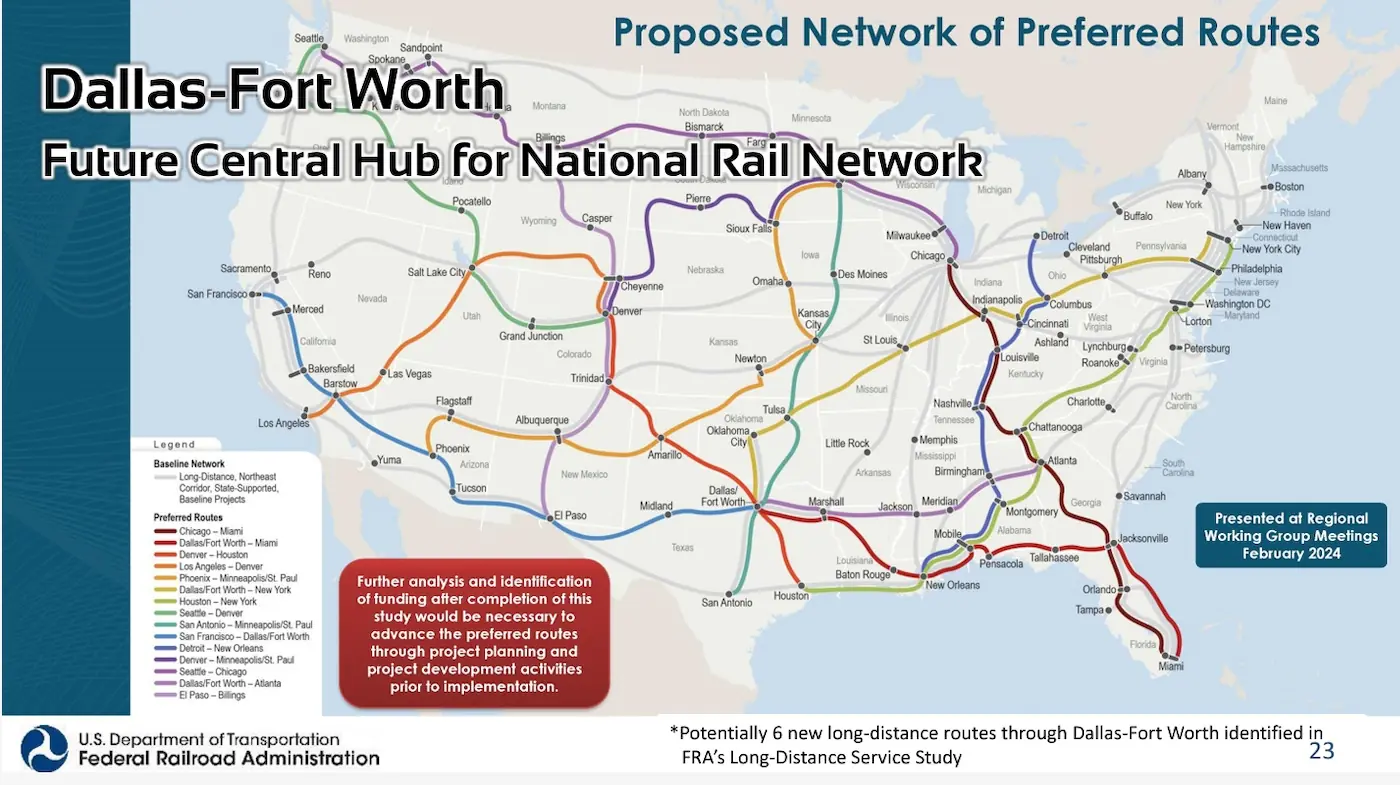

That is why the line to Fort Worth feels so important. Morris presented a map from the Federal Railroad Administration that showed a potential national rail network. This Long-Distance Service Study was made public in February. It displays a tangle of paths crisscrossing the country, a rail system dreamed up like Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System. Potential routes shoot out from North Texas like a star. A line to Fort Worth could be part of a train ride from Houston to Colorado. Or trips west to New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Without Dallas to Fort Worth, Morris said, Austin would get cut out completely. Riders would head south to Houston, but cut west to Bryan and south to San Antonio. Adding Fort Worth adds Austin, he argued.

This portion of the presentation was made, in part, to try to silence critics who have argued that the existing Trinity Railway Express is enough of a connection between Dallas and Fort Worth. Morris believes he has a responsibility to deliver a high-speed rail line west, in part, so that North Texas doesn’t miss out on connectivity to the rest of the country. It’s an educated guess, a bet on the future of transportation in a booming state, in a region of 8 million people expected to grow to 11 million by 2045.

“The Dallas-Fort Worth Area is right in the middle of several lines being proposed,” Morris said. “Any of those lines could be high-speed. You could have at-grade service or high-speed rail depending on the need of the corridor across the country.”

After Dallas “paused” its support to Fort Worth via that resolution, the COG dropped its insistence that its preferred route into downtown was the only option for Dallas to consider. Instead, consultant engineers went to work to create an alignment that wouldn’t draw the ire of the region’s largest city.

Dallas now holds the cards. The COG has a March 2025 deadline to complete what is known as an Environmental Impact Statement, which presents the federal government with 30 percent of the project’s design to consider exactly what this document’s name says. The EIS also includes more specific cost and ridership estimates. That document must be approved before the COG begins engineering and searching for financing. Once the federal government approves, that alignment is locked in, or the process begins anew.

This is why the COG called the 45-member Regional Transportation Council (RTC) to Arlington for a two-hour workshop Thursday. It wants assurances that Dallas is happy with the direction in which the project is now headed. Planning a project like this high-speed rail route—a cost floor of $6 billion, nearly three dozen miles across two counties and four cities—is messy business, a spaghetti bowl of interests. One city’s opposition could tank the whole process. The feds want to sign off on projects that are “shovel ready.” If a city formally opposes the plan, it puts the entire route in jeopardy.

Morris gave the city of Dallas “homework.” Does this line solve your problems? If so, he said, he would consult with the federal government to make sure bumping the route west is appropriate, considering the environmental study is already underway. The feds could approve the new alignment, or they could require additional design work that may delay the process by one year. Morris hopes the RTC will vote on the matter by August.

“I’m not worried about adding a year to the schedule if it pulls us together in a consensus position,” Morris said. “It’s better to get into a potential delay and not have a fatal flaw than to pursue a more expedient path and potentially have a fatal flaw in a Dallas resolution that does not change.”

Basically, a year is better than a decade, which is about how long planning has already been underway for this Fort Worth line.

Of the 31-mile route, the single mile in downtown Dallas was the only portion in question. Fort Worth and Arlington’s underground rail stations remain in the alignment, although Arlington voters will need to approve a formal arrangement with a public transit authority for the city to get its stop. The rail still traces along Interstate I-30’s path as it comes east into Dallas. It still surfaces near the Hampton Road exit. But as the line approaches downtown, it makes a 90-degree cut south, crossing over the viaducts as well as Riverfront Boulevard and Interstate 30. It essentially bypasses the developable land downtown, which seemed to be the primary concern among most members of the Dallas City Council. It will shuttle passengers to Fort Worth in half an hour.

Four of the five Dallas representatives present for the RTC meeting (Councilmembers Omar Narvaez, Jesse Moreno, Adam Bazaldua, and Chad West) spoke in favor of the line itself, but said they needed more details about height and where, exactly, the line would be placed downtown. Councilmember Cara Mendelsohn said she was “skeptical” of high-speed rail ever being built and that the talks were “extremely premature” because Amtrak hadn’t secured financing or completed land acquisition south to Houston. No one else voiced her concerns.

Narvaez, who chairs the Council’s Transportation Committee, said he wanted to see the economic study before making a final decision. But he supports the original line through downtown.

“I think once we get that [study] back, we’ll have a lot of answers to the questions my colleagues had on economic impact concerning what the western line can do versus the original,” he said after the presentation. “Just because I may have strong feelings about the first line—I’m in favor of it—I still want to respect my colleagues and respect the body to give them enough time to look at these things and allow them to make a decision on what they feel is right for Dallas.”

But Morris clearly wants an answer sooner. He viewed the original proposal as a gift to Dallas. He would figure out how to pay for an air-conditioned people mover to shuttle riders the half-mile or so from the high-speed rail station to the convention center and Eddie Bernice Johnson Union Station, which Dallas views as its at-grade mixed-use and public transportation hub. (They’ve used Denver’s highly successful redevelopment of its Union Station as a north star.) The new alignment could include a connection to the convention center, but it would be up to the city to figure out connectivity further into downtown.

But this is now about a bigger picture. Here’s what Morris told the City Council in January: “It seems very unlikely we would want to build high speed rail between Dallas and Fort Worth if we did not have a leg that connected us to all the other Texas cities.”

Thursday’s presentation showed how Morris envisions the system as a nexus for the future of American transportation. The question now is whether he has found a route that is friendly to downtown Dallas and to which the City Council will give its blessing.

Author