Before taking the helm of the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum on Jan. 1, 2013, Mary Pat Higgins did not consider herself a historian or a museum person. She joined from The Hockaday School, where she worked for more than two decades, ultimately as associate head and CFO.

Despite her long career in education, Higgins says the new role at the museum came with some learning curves. “I often joke and say it was the best midlife crisis ever,” she says with a laugh. “I had never been a fundraiser, so I had to learn all those things when I was 48.

“It was energizing and a little scary for a couple of years,” she adds. “I worked with an incredible team of volunteer leaders to help make this long-held dream a reality, to start the fundraising process, and to design the exhibition in the building for the new museum. In some ways, we all learned together.”

Her first year, she had the opportunity to go to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem. In her second year, she went to Poland and Germany to visit some of the death camps and historic sites with the man who was leading the Dallas museum’s exhibition design process.

“Those two learning opportunities were transformational for me as far as understanding and embracing our mission,” she says. “That immersive experience helped me have a much deeper understanding of the history of the Holocaust.”

The museum was founded in 1984 by about 125 Dallas-based Holocaust survivors, Higgins says, with the idea of honoring their loved ones who were victims of the genocide. What started as a small exhibit in the basement of the Jewish Community Center has morphed into a 55,000-square-foot building in Dallas’ West End that opened in 2019.

In 2023, the museum reached nearly 218,000 people, including more than 132,000 through public programming, events, field trips, and more. Beyond that, visitors come from all 50 states and around the globe from 78 countries.

Higgins anticipates that the total number will climb to around 280,000 visitors by the end of 2024—190,000 of whom are students through the museum’s programs with local school districts such as Dallas, Coppell, Richardson, Euless, Bedford, and Hurst.

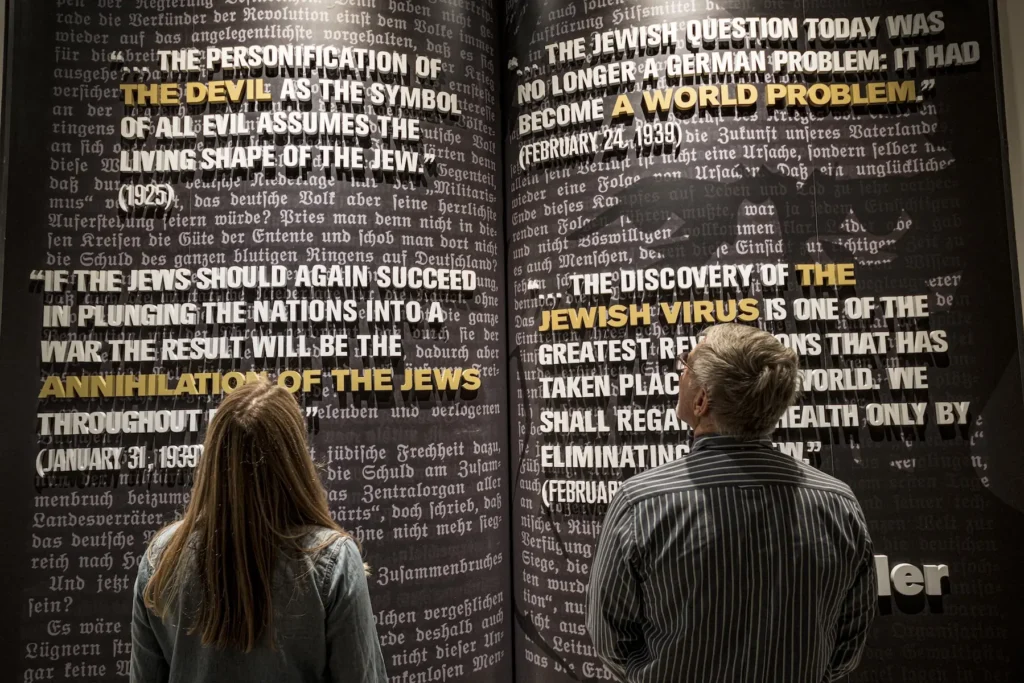

“Education is at the heart of our mission,” she says. “When we built this museum, it was designed to be appropriate for 6th to 12th graders because our intent was to have as many grade school students visiting as possible. We don’t try to shield our visitors from some of the more graphic images. There’s some very difficult content people learn when they’re here. But we’re also careful to hold up examples of people who stood up for themselves and others to make a difference.”

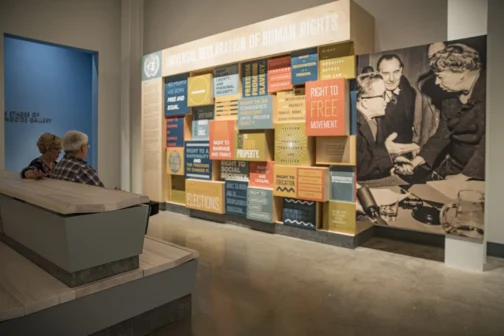

Although the museum’s roots date back to the education and remembrance of the horrors of the Holocaust, claiming the lives of millions of Jewish people, today’s iteration features several standing exhibits throughout the Holocaust/Shoah Wing, Pivot To America Wing, and the Human Rights Wing, including the 10 Stages of Genocide Gallery, showing different genocides throughout history beyond the Holocaust and how they evolved.

“What’s most gratifying is to be with a first-time visitor who goes through the Holocaust wing and learns things they never had any concept of,” Higgins says. “It opens their eyes to why the Holocaust is often referred to as the paradigm of genocide. It’s so unique in so many ways. But then, as we go through the rest of the museum, they’re so surprised by the extent of the additional content.”

The museum’s current special exhibit, Hidden History, tells the story of 20,000 Jewish people who were able to escape from Germany and Austria during the late 1930s by fleeing to Shanghai, one of the only places at the time that would take Jewish people in as refugees. In March 2025, ‘A Better Life For Their Children’ will open at the museum, detailing the work of Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald during the era of segregated schools in America.

Under Higgins’ leadership, the museum has reimagined its foundation by starting with the Holocaust and building from that point onward in history, detailing the human rights angle and how those lessons from nearly a century ago are still present today. “We teach about other genocides and human rights violations,” she says. “It gives us a broader canvas. Often, the history we learn about our own country is pretty horrifying.

“We’re not born with hatred—we learn hatred,” Higgins adds. “And I think we can unlearn that. I hope that the future leaders of our community can understand how devastating prejudice and hatred can be. It’s a slippery slope. I have faith that some of the kids who come through this museum will understand that and will be incredible leaders in our community and make it a better place.”

Author