“What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore—and then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over—like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode?”

Langston Hughes’ 1951 poem “Harlem” refers to the treatment of Black Americans at the time, when Jim Crow laws and other discriminatory practices limited opportunities and rights for people of color. Among those who spend their time navigating the complex world of immigration, the poem still resonates.

The consequences of these deferred dreams, experts say, is not only devastating and disruptive for individuals, but is a threat to employers and the overall economy. A divided nation stands in the way of reform that could turn things around.

If the U.S. decided its economy would limit itself to functioning on the technology, mindset, and communication innovations of the early 1950s, it would not be the economic powerhouse it is today. But for employers who want to fill positions with highly skilled foreign professionals, the system that guides the process uses limitations that have roots in a law passed in 1952. The H-1B Visa program allows employers to bring in workers to fill specialty occupations in fields like mathematics, engineering, technology, and medical sciences, but the demand for these visas so vastly outnumbers available spots that securing one is more kin to winning the lottery than landing a job.

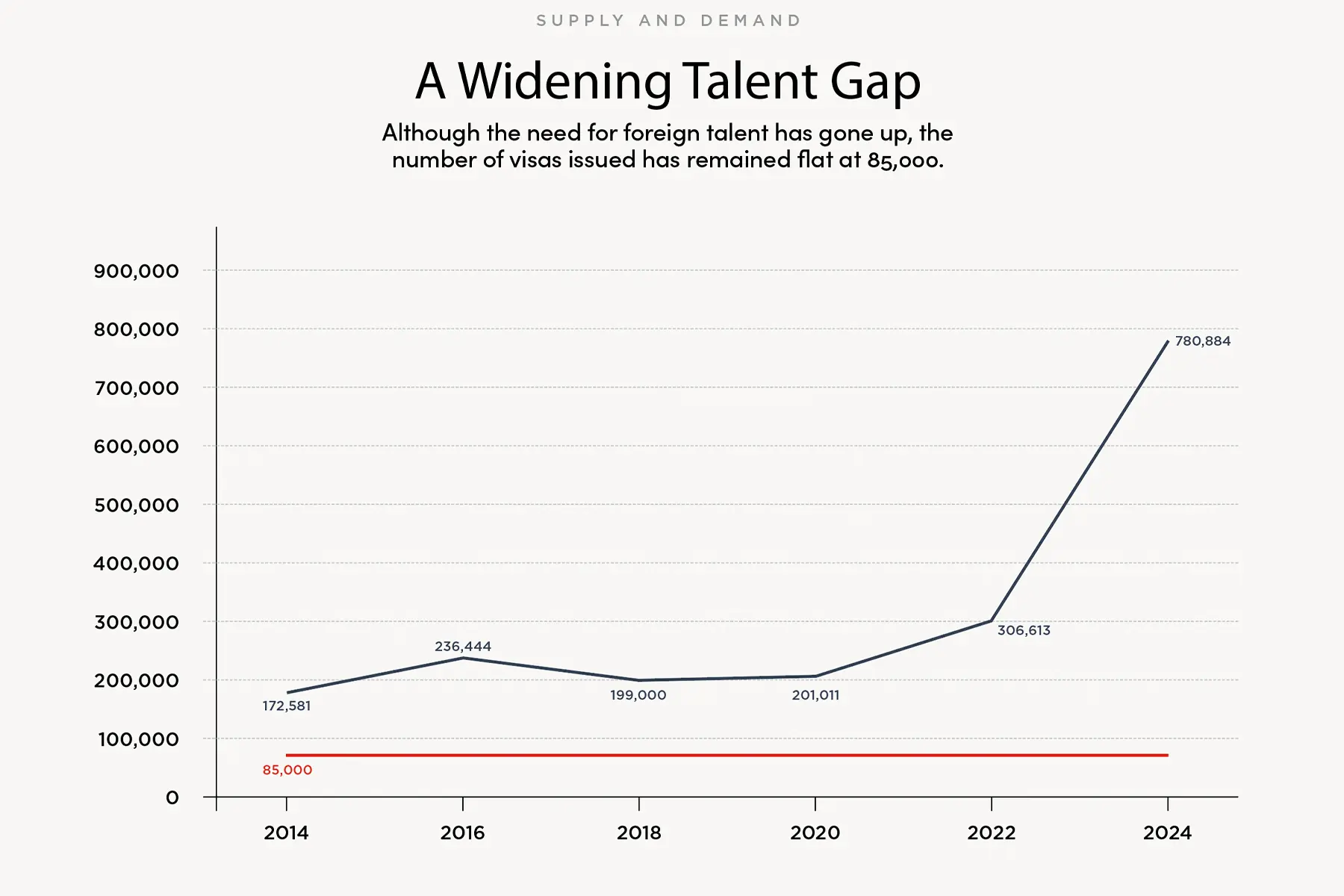

Although the total number has fluctuated over the years, today 65,000 H-1B visas are granted annually, with 20,000 more added for those with a master’s degree or higher. Although that may seem like a significant number, there were 780,884 total H-1B visa registrations in 2024. That means only about one in 10 workers who have a job offer at a U.S. company were able to obtain a visa allowing them to take the position and legally work.

The gap between the number of people allowed to work in highly skilled positions and those applying is only widening. (See graph). In 2022, there were 308,613 total registrations, up dramatically from 172,581 in 2014. These are not individuals applying for refugee status or asylum or merely hoping to get to the United States, but rather educated foreign workers who have job offers at companies in America and want to come work, pay taxes, and build their lives here.

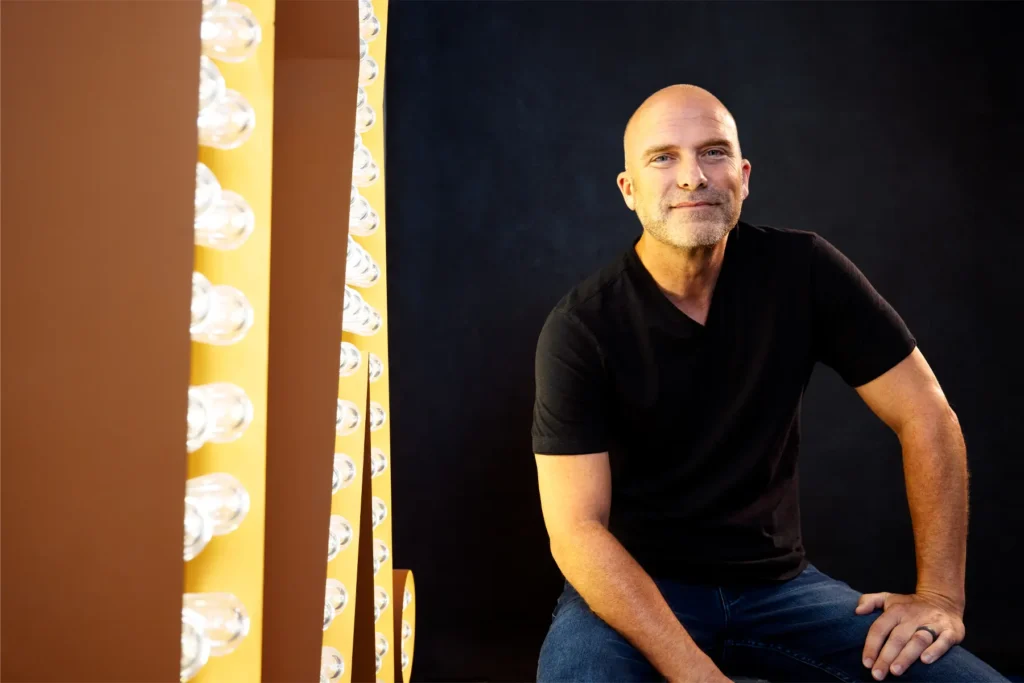

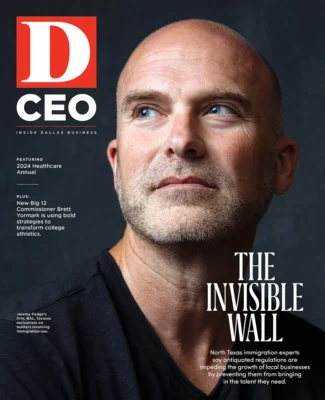

“Our immigration system is broken,” says Jeremy Fudge, CEO of Richardson-based law firm BAL. “The border is chaotic and broken, but highly skilled immigration is equally broken.”

Nearly 100 percent of BAL’s work involves helping corporate clients navigate the immigration system to try and fill their open positions with skilled labor from abroad. The region’s strong economic success is founded on companies being able to fill its positions with the best talent possible.

“North Texas has a diversified economy, which makes us both vulnerable and resilient to immigration changes and challenges,” Fudge says. “Our job market spans healthcare, airlines, financial services, school districts, manufacturing, telecommunications, and more—all of which rely on skilled foreign workers to fill critical and open positions that would otherwise remain vacant.”

‘We Can’t Rely on a Lottery’

Many agree with Fudge that the country’s immigration system is broken. However, experts say there are a few common myths connected to the system. From a talent perspective, those vying for H-1B visas are not taking jobs away from Americans. Employers must prove they can’t fill the position domestically when applying to fill it with a foreign worker.

It is much faster, easier, and cheaper to hire an American for the same position. Filing for a visa is increasingly expensive. A couple decades ago, the fee was $300 per employee; today it is 10 times that at $3,380. Expedited processing nearly doubles the cost, and many employers pay immigration lawyers to navigate the process and bring in the foreign workers.

“The claim that skilled immigration is taking away jobs from Americans is a myth,” Fudge says. “Any company we work for would prefer to hire an American with the same skillsets because this isn’t cheap.”

If a company has an international presence, the proliferation of remote work may mean that it sends the worker to an office in a different country where the immigration system is more efficient or open. Sometimes, the business may take the operation overseas or offshore to get the talent it needs. In the end, the American immigration system robs the economy and the tax base. “The companies will persist. The Googles and the Amazons are going to find a solution,” Fudge says. “We are only hurting our country at the end of the day because business goes on.”

Along with being unreliable, the U.S. system frustrates employees and employers by not considering the demand for certain types of positions. Rather than prioritizing jobs in healthcare, for example—the U.S. is experiencing increasing nursing and physician shortages—the H-1B lottery is random, meaning that a rural hospital that needs a cardiologist may lose out to a software enterprise adding another engineer. In addition, there’s a limit on the number of workers per country, regardless of job. “This is no way to manage your workforce,” says Karen-Lee Pollak, managing partner of Pollak PLLC. “We can’t rely on a lottery.”

Working Within the System

Pollak was born and raised in South Africa and came to the U.S. after attending law school there. She has personal experience navigating the H-1B visa system and was fortunate to secure one to be able to obtain a job as a lawyer in America and eventually open her own practice in the United States. The experience helps her empathize with her clients and the employees they are bringing in. “I have been through the gamut and can understand what they are going through from a mental and psychological perspective,” Pollak says.

She remembers questions about whether she would have to return to her home country while in the U.S. Even though she had a job lined up in America, she lived in fear that she would have to uproot everything she had worked so hard for. However, she was able to get an H-1B visa on her first try and has since gone on to become a U.S. citizen. She is one of the lucky ones. “My whole life was at stake,” Pollak says. “It caused a lot of sleepless nights.”

Others aren’t so fortunate. Many people will continue to stay in school and obtain more degrees to stay in the U.S. on a student visa, which is easier to obtain than an H-1B. Many foreigners spend years being educated in American schools only to have to return to their home country because they can’t get a H-1B visa, despite having American job offers. The increasingly important science, technology, engineering, and math professions are suffering the most. Between 1988 and 2017, STEM degrees obtained by foreign students grew by 315 percent. There are more foreign students who graduate with master’s and doctoral degrees from American schools each year than there are available visas. Immigrants earned nearly half of all doctoral degrees issued in the U.S. in 2022, according to the Center for Immigration Studies.

Those who cannot continue to study and don’t get a visa must return to a country they may not have been back to for years. Other workers try other approaches to stay in the country and keep their jobs. A green card can get a worker out of limbo, but those are also tough to get and are limited by country quotas. Sometimes, the wait for a green card can be as long as eight or nine years.

“There are very few ways to get a green card,” says Kathleen Martinez, managing partner at Martinez Immigration, which focuses on family-based cases. “Marriage and having a family member in the country are two of the only options.”

Reform an Economic ‘Slam Dunk’

The term “immigration reform” may include common sense changes to the system to allow foreign workers to accept the jobs offered to them, but it’s also associated with the turmoil at the border and undocumented immigrants, making any changes to the existing rules nearly impossible, experts say. The lack of movement in this realm has caused employers to get creative by leveraging the different visas available to foreign workers (see sidebar), but smaller companies don’t have the resources to get by without filling positions and lack international offices to keep talent in the fold.

Still, there are ways employers and individuals can get involved. For example, lobbying efforts and coalitions can amplify a company’s voice. In May, Google reached out to the Department of Labor urging it to modernize its immigration rules to secure needed talent in artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, both of which are essential to the economy and national security.

“The U.S. is one of the harder places to bring talent from abroad, and we risk losing out on some of the most highly sought-after people in the world,” wrote Google’s Head of Government Affairs and Public Policy, Karan Bhatia.

Pushing for an increase in the number of annual H-1B visas to reflect modern realities can be augmented by advocating for a system that prioritizes types of workers rather than a pure lottery, experts say. Canada, for example, assigns points to immigration applicants and has a list of occupations that qualify potential workers for express entry.

In America, illegal immigrants contribute to the tax base. In 2017, 575,00 undocumented immigrants paid nearly $500 million in state and local taxes in North Texas alone. “Reforming highly skilled immigration is such a slam dunk,” says Pia Orrenius, vice president and senior economist at the Federal Reserve of Dallas. “It is a win-win for the worker and the country. On net, the country benefits.”

In recent years, conservative administrations, traditionally the party of free markets, have been more restrictive toward foreign immigration, and the political fluctuations create an added layer of uncertainty.

This past summer, President Joe Biden announced that individuals who were illegally brought to this country as children, so-called Dreamers, would not be separated from their families if one of the family members was married to a U.S. citizen and they had been in the country for at least 10 years. “Whoever is president needs to give Dreamers a pathway to citizenship without having to get married,” Martinez says.

As Fudge noted, North Texas’ diverse economy makes it both vulnerable to and resilient against the fluctuations of the immigration policy. An internal survey of BAL clients showed that 59 percent found it easier to meet foreign talent needs in the last four years, but more than half said they were readying for possible changes based on the presidential election. For Pollak, it is simple: “Let market forces play. If you have jobs for people, hire them.”

Although the H-1B is the most common visa used by employers, there are H-1B Visa

For people in a specified professional or academic field or with special experience who have a college degree or higher or the equivalent work experience. They have a residency cap of three years and require a job offer from a U.S. employer.

H-2A/H-2B Visa

For seasonal or peak load temporary workers in agricultural (A) or non-agricultural (B) settings; they usually do not extend beyond a year.

I Visa

For members of the foreign press, including reporters, film crews, and editors representing foreign media outlets. Residency is indefinite if the holder keeps the same employer.

P–1A Visa

For those coming temporarily to the U.S. for the purpose of competing in a specific athletic competition.

E-3 Visa

Grown out of a trade deal between the U.S. and Australia, this visa is for Australian nationals coming to America to perform a specialty occupation. dozens of other types.

Author