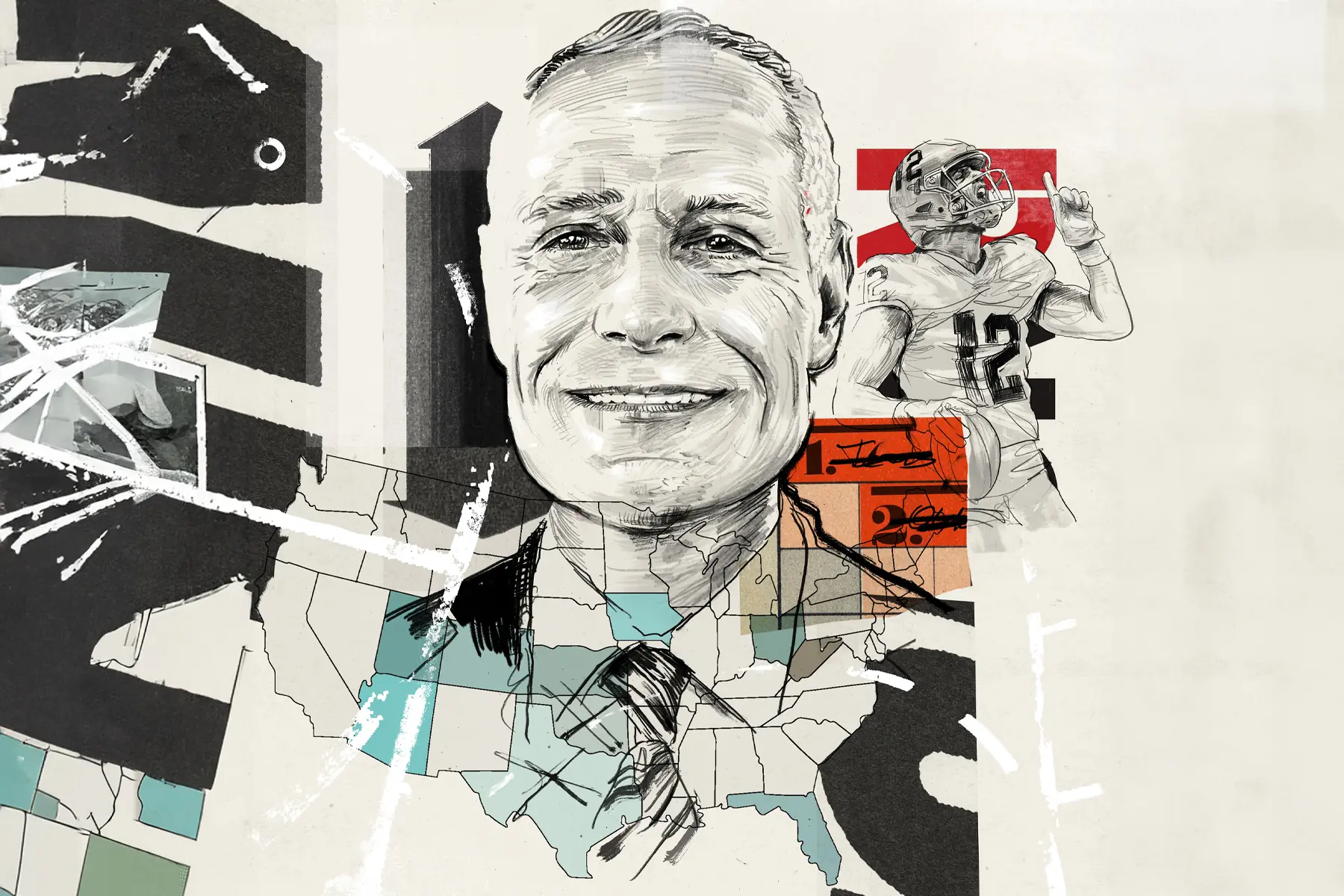

Two years ago, Brett Yormark stood before a fleet of reporters at AT&T Stadium in Arlington during his first public media days as commissioner of the Big 12 Conference and declared, “The Big 12 is open for business.” The statement wasn’t hyperbole but rather a vow—a vow to everyone in college athletics and any business looking to get involved in college sports that he was taking, and making, phone calls. After all, the Big 12’s two most prominent brands, The University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma, had bolted to the SEC. Yormark needed to find a way to keep the Irving-based conference from becoming irrelevant or, worse, extinct.

According to Yormark’s predecessor, Bob Bowlsby, who served as Big 12 commissioner from 2012 to 2022, member institutions began putting together “fallback plans” should the conference crumble after the departure of the Red River rivals. The schools would be negligent to not do so; after all, Bowlsby told Texas lawmakers in August 2021 that the league could suffer a 50 percent media revenue hit in the wake of the schools’ departures. But Bowlsby was able to score four institutions (the University of Houston, Brigham Young University, the University of Central Florida, and the University of Cincinnati) from non-power conferences to steady the ship and avoid what inevitably came for the Pac-12. Shortly after, Bowlsby retired, sharing with D CEO that “lawsuits and financial initiatives” played a major part in his decision to step away. Within three months, Yorkmark arrived.

Up first on the newcomer’s docket was scoring a new media rights deal for the conference. Its revenue was far behind the SEC’s and Big Ten’s, and the easiest way to solidify trust from member institutions was to close the gap by inking a new media deal. The existing contract wasn’t set to expire until 2025, but fewer than 90 days into his tenure, Yormark got aggressive. He nabbed a $2.28 billion contract with ESPN and FOX that will run through 2031.

Had he not done so, he says, he might not have a job today. “I didn’t know that there was only one big deal left, but it kept us afloat,” Yormark says. “We could have easily ended up like the Pac-12 had we not knocked it out early.”

And so, the new commissioner was off to the races. He secured a deal that would be the Big 12’s life raft, and without networks willing to dish out another massive media contract, the Pac-12 dissolved shortly thereafter. Yormark capitalized on the demise by adding four former Pac-12 institutions (the University of Arizona, Arizona State University, the University of Colorado, and the University of Utah). He also brought marketing in-house and hired the Big 12’s first ever CMO. It effectively saved the conference millions of dollars. Yormark then brought sponsorship sales in-house; as a result, sponsorship revenue grew by 80 percent in fiscal year 2023. Ticket revenue also grew by 23 percent in 2023. Today, the Big 12 has 48 employees—when Bowlsby left, it had just 23.

“Brett isn’t unwilling to challenge the status quo—and he was right to be aggressive in media negotiations,” says Bill Hancock, who served as executive director of the College Football Playoff from 2013-2024. “The Big 12 had one of the best commissioners ever in Bob Bowlsby, but Brett is the right guy at the right time for the Big 12.”

BREAKING THE MOLD

Yormark doesn’t fit the mold of a traditional conference leader. After all, he has never worked for a university or an institution’s athletic department. But when the Big 12 was looking for someone to fill Bowlsby’s shoes, board members were not interested in a status-quo hire. “Brett was hired to be bold,” says TCU Athletic Director Jeremiah Donati, who will become the Big 12’s AD executive committee board chair in 2025. “He’s a big, bold thinker and a dealmaker. He’s challenging athletic directors, presidents, and chancellors to think differently about our business model.”

Yormark’s business acumen has attracted many opinions over the years. Forward-facing roles at NASCAR and RocNation (Jay-Z’s entertainment company), along with being CEO of the Brooklyn (formerly New Jersey) Nets and New York Islanders (he relocated both franchises to Brooklyn), have all set him up for such criticism—some fair analysis, others not so much. The Nets’ relocation was a huge success; the Islanders was the opposite. Yormark has been noted by various news outlets as a “serial exaggerator,” a “less-than-credible salesman,” and, in just a short stint as the Big 12’s commissioner, likened to P.T. Barnum, an elaborate charlatan who pioneered the circus industry. The comparison to Barnum isn’t so offensive. After all, when Yormark and his twin brother Michael (now president and chief of branding for RocNation) were just 7 years old, his mother, who was a successful interior designer in New York, took the boys from their home in northern New Jersey to Madison Square Garden to see the circus. It was there the twins first fell in awe of live events.

Like Barnum, Yormark is an idea man; Hancock describes him as a hustler and a disruptor. “The Big 12 needed to take the plunge into the world of business, marketing, and sales in a significant way after losing UT and OU,” Hancock says. “And Brett has a thousand ideas every day. There were days where I would have a dozen phone calls with him, none lasting more than 90 seconds, but he would just bounce ideas off me.”

Yormark is two years into his tenure as commissioner. To say the last two years in college athletics has been chaotic is an understatement. Amidst conference realignment madness, the shifting name, image, and likeness regulations and rulings, the changing media landscape, and the emergence of private equity, Yormark aims to be at the leading edge of the reconstruction. After all, he wasn’t hired to have a steady hand; he was hired to disrupt.

Rumors surfaced in July that Clemson University and Florida State University have had discussions with the Big 12 about joining the conference. “In a world where realignment is a living, breathing thing that will never be put to bed, I expect Brett to be very aggressive,” says Donati at TCU. The report is unconfirmed, but the institutions currently have five active lawsuits against the ACC. Nabbing basketball powerhouse UConn is also on the table for the conference.

“When opportunity presents itself,” he says, “I take advantage of those moments.”

THE NAMING RIGHTS KING

When Yormark was a child, his mother, Arlene Sloan, catered to high-profile clientele at her interior design firm, working with sports franchise ownership groups like the New York Yankees and New Jersey Nets. So, she opened the door for her sons in the sports industry. In college, Yormark thought he was on the path toward a career on Wall Street, but after an internship in the financial center, he realized a job on the trading floor wasn’t for him. After he graduated from Indiana University in 1988, his mother helped him get a meeting with Nets ownership. Yormark earned his first job as a ticket salesman for the NBA franchise.

After cutting his teeth in the business, the Detroit Pistons recruited him to sell sponsorships. In 1994, the Nets brought him back as vice president of marketing and eventually promoted him to senior vice president of marketing. Four years later he left for NASCAR. As the VP of corporate marketing there, Yormark orchestrated the largest naming rights deal in American sports history at the time, convincing the now-defunct Nextel Communications to invest $750 million into a 10-year sponsorship that would rename stock car racing’s premier circuit from the Winston Cup to the NASCAR Nextel Cup.

“When you’re doing naming rights deals, you look for someone who needs it—someone who needs a shot in the arm,” Yormark says. “To this day I use that same recipe. At the time, Nextel’s CEO [Tim Donahue] was a huge NASCAR fan, and because Nextel was a challenger brand in its space, I targeted the company that I felt needed it most, and that led us to Nextel.”

In 2002, Nextel generated $8.7 billion in revenue. Two years later, after making the investment Yormark sold them on, the company raked in $13.4 billion.

In 2005, Yormark was on the move again. He boomeranged to the Nets, rocketing up to become the team’s CEO. By then, the Nets had become one of the worst-run teams in the NBA. Yormark returned to rebuild the Nets’ brand. Alongside new owner Bruce Ratner, who acquired the team for $300 million in 2004, a decision was made to relocate the team from New Jersey to Brooklyn and build a new stadium in the neighborhood the Brooklyn Dodgers vacated when the MLB team bolted for Los Angeles in 1957. “Most people told us this relocation was never going to happen,” Yormark says. However, 36 eminent domain lawsuits and $1 billion in construction costs later, the new arena was built. And once again, Yormark found himself leading a naming rights deal, this time for a new 18,000-seat stadium. Who did he target? Another brand looking to break through: the British bank Barclays.

At the time, the bank was searching for a platform to Americanize the brand, and controversial Barclays chief executive Bob Diamond eyed American sports to do so. So, Yormark swooped in for the close. “They had other options they could pursue—he could have done a big deal with Madison Square Garden or Yankee Stadium,” Yormark says. “Barclays was a challenger brand to the big financial institutions in the U.S. So, as my presentation was coming to an end, my close was, ‘Bob, you come across as a guy who likes to create legacy, not inherit it.’ He answered me, ‘Yes, you’re absolutely right.’ Within a week’s time, he called me up and said, ‘Let’s go build a legacy in Brooklyn.’”

And just like that, another huge deal had closed. This time, Yormark scored $400 million in a 20-year agreement.

I don’t want to wake up tomorrow and read that [some other conference] partnered with a private equity firm and someone else was the first mover in that space. I like being a first mover.

Brett Yormark

THE NEXT WAVE

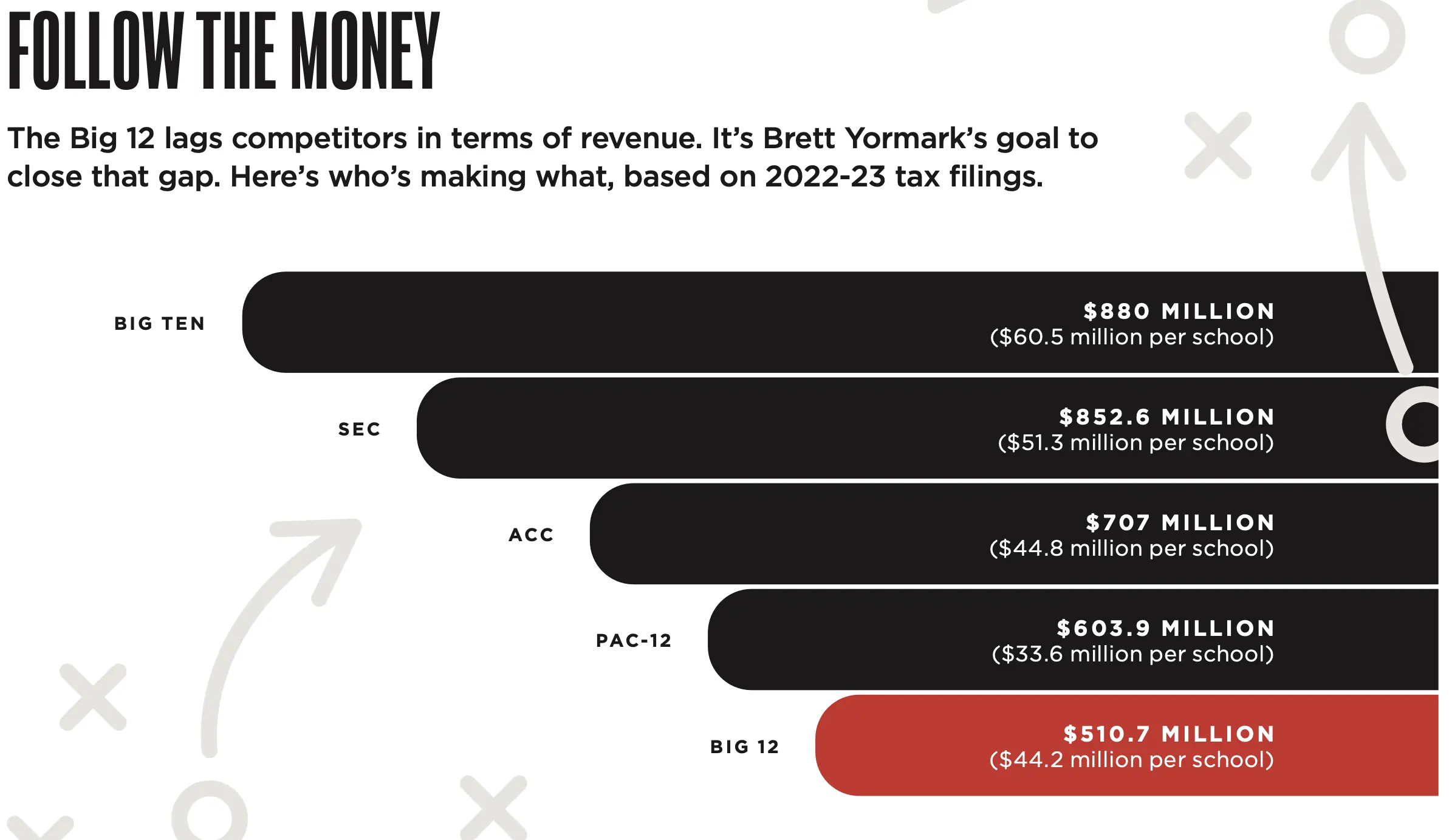

Of the five power conferences that were around in fiscal year 2022-23 (now down to four after the Pac-12 dissolved), the Big 12 came last in revenue at $510.7 million, according to tax filing disclosers. The SEC ranked No. 2 at $852.6 million—the Big Ten edged out the SEC by $27 million. Of those earnings, the Big 12 distributed roughly $44.2 million to each institution. SEC schools pocketed $51.3 million apiece.

Yormark’s top priority is closing that divide—a chasm caused by media demand, which dictates how grand each conference’s media rights deal is. Yormark signed a shorter-term media contract than expected: Inked only through 2031, he wants to get back on the open market, and fast. When the current deal ends—or two years before that if history has taught us anything—Yormark will attempt to negotiate a much larger deal—one that rivals the Big Ten’s and SEC’s. “Wherever I’ve been, I’ve been a revenue generator,” he says. “I’ve built brands and businesses, so I’m in the perfect place for that right now.”

But can the Big 12 ever command its rivals’ numbers? “I don’t have a crystal ball,” Hancock says, “but I think that’ll be a challenge. Getting to the Big Ten and SEC’s level is tough. But can they be successful coming up little bit short? Absolutely, my goodness. You know, revenue is also about facilities, and it’s going to, pretty soon, be about NIL—but they’ll do fine. One thing I know about Brett is he is going to hustle.”

Donati seconds Hancock’s confidence. “As we grow our revenue, those leagues will continue to grow theirs,” he says. “But I think we will make some serious headway closing the gap.”

Today, Yormark once more finds himself amid a controversial naming rights process to drive revenue growth. He’s eyeing a possible deal that could rename the Big 12 to something like the Dr Pepper 12, the Gatorade 12, or the Allstate 12. Yahoo Sports reported the latter in June as a real possibility—according to the outlet, the deal would be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Yormark was unwilling to confirm the specific sponsors he’s negotiating with. Still, all signs indicate that he’s determined to be at the leading edge of these type of deals.

“We’re entering the period of commercialization of collegiate athletics,” he says. “A big part of our value creation is, can we further monetize what we do and how we do it—both at the conference and member institution level? I am going to explore any and all possibilities to drive incremental resources to the conference. So, do I think naming rights create value for the conference? 100 percent. Only time will tell whether it’s the right thing to do. But these types of deals work and drive strategic and financial value.”

Not all are convinced of the gameplan. “There are some dinosaurs in our business who are in a panic about the naming rights deal,” Hancock says, “But I say, ‘Why not?’ If it will help their schools stay more relevant, why not?” Bowlsby praises Yormark for his willingness to push the envelope. “I think any commissioner worth their salt today has to be open-minded to new ways of structuring revenue and creating distributable revenue for the members,” he says.

Pushing the boundaries even more, Yormark aims to be the first commissioner to score a private equity investment in his conference. When news broke of his naming rights goals, The Athletic was the first to report that Yormark had initial discussions on a potential private equity investment into the conference. According to The Athletic, CVC Capital Partners, a Luxembourg-based investment firm, pitched the conference on a possible investment of $800 million to $1 billion in exchange for a 15 to 20 percent ownership stake in the conference. Yormark did not confirm the validity of that meeting, but one thing is for sure: He won’t be beaten by the Big Ten, SEC, or ACC in securing PE dollars.

“I don’t want to wake up tomorrow and read that [some other conference] partnered with a private equity firm, and someone else was the first mover in that space. I like being a first mover,” he says. “I’m looking for a PE firm that brings capital resources and strategic acumen. When you engage with private equity, you want both. I would not advocate for just taking the capital.”

Private equity in college athletics is here to stay. The world’s most active PE firm focused on sports, RedBird Capital, partnered with Weatherford Capital to launch Collegiate Athletic Solutions this past May. (Both RedBird and Weatherford have large DFW operations.) The investment fund aims to partner with up to 10 universities to infuse between $50 million and $200 million into athletic departments. “As I’ve become more well-versed in private equity across college athletics, my thought is: be careful,” Hancock says. “What would a conference, a school, or anybody involved have to give up in order for the private equity firm to make their money? Would a private equity owner care about women’s soccer? Or cross country? Or wrestling? I think we all know the answer, but I don’t want to go there.”

So, it could be a game of giving up this for that. The concerns are similar for Bowlsby, but he thinks the recent ruling allowing college athletes to share revenue generated by their teams is a bigger worry. In May, the NCAA and the power conferences voted to approve a settlement for three antitrust lawsuits, most notably House v. NCAA. In March 2025 the final ruling will come. If passed, universities and conferences would be able to directly pay players through revenue sharing. As a result, the era of amateur athletics would soon be over.

“With revenue sharing, I think what you’ll see first is men’s sports begin to decline in numbers,” Bowlsby says. “Once Title IX and gender equity aren’t as big of a challenge, you’ll start to see women’s sports go away. Overall, the institutional breadth of programs will be narrower. There will be fewer sports, but more money to go around to the sports that are left. I think that’s an inevitability. There’s only so much money to go around. But, at this point, the plaintiff’s lawyers have learned that they can make a lot of money off lawsuits against the universities, the conferences, and the NCAA, and they’re going to just keep their jaws locked on our ankles until we stop bleeding.”

Like Donati at TCU, Yormark is in favor of rewarding the athletes: “If you’re part of the value equation, you should be rewarded for that,” he says.

The commissioner is far from finished remaking the Big 12. He knows he has a long way to go to get the brand where he wants it—and he won’t leave any stone unturned. “There was a lot of uncertainty for the Big 12 when I took this job due to OU and Texas leaving,” he says. “But I saw a chance to transform and reinvent the conference. And today, we are more relevant than ever as a conference. There’s probably no deeper conference in America.”

Yormark is certainly not threatened by the next wave of realignment—which will inevitably come. Instead, his confidence will only spark aggression. “Whether what’s to come is consolidation or not, our conference and institutions will be part of the conversation,” he says. “I’m convinced of it. College athletics is in a period of change. We are going through a period of transformation. And where I come from and where I’ve been before, in those moments, you double down. You don’t take your foot off the pedal.”

Author