In this excerpt from “Wards of the League,” a new book published by TCU Press, brothers Connell and Giles Miller take possession of the defunct Yanks assets and try to get their Dallas Texans operation off the ground.

By mid-February 1952, the league would release all of the Yanks’ leftover assets and ship them down to Dallas. There was excitement and anticipation building as an allegedly full truckload of supplies, player contracts, records, and equipment came rolling down south to their new home. The Millers were about to receive the world’s largest Christmas present. The assumption was that the tractor trailer carried the contents of a ready-made team.

Upon arrival, the brothers and staff were taken aback when the door was opened. It was like some sort of practical joke. The truck was virtually empty. There was nothing remotely resembling anything close to football contents, aside from a couple of file cabinets and a few boxes of old paperwork. Unbeknownst to Bell, the weight room and field equipment, along with everything else, had been sold off by Collins in an attempt to recover his losses. While Connell and Giles didn’t anticipate receiving anything that was bolted down in New York or a lifetime supply of ankle tape, they did expect to at least be sent one football. They weren’t, which meant this was going to be yet another set of unplanned expenses.

Even before the truckload setback, a myriad of details still lingered. On February 18, a board meeting was held where it was proposed and approved to lease club and ticket offices at the corner of McKinney Avenue and North Akard Street for $500 a month from J. Curtis Sanford, the same J. Curtis Sanford who was on the team’s board of directors.

Once it became apparent that there were no real assets, such as office supplies or furniture, Giles Miller would go on a shopping spree. He went with Sanford and fellow board member Jack Vaughn to the Kathy Office Supply store nearby and purchased all the necessary equipment for the new office setup on credit terms. In fact, he bought more than they needed.

After all the furnishings had been delivered, a few others in the organization would start to bring in some high-end additions of their own. Vaughn provided an ancient Etruscan couch to the merriment of everyone there. The place was filling up fast and, unfortunately, eclectic quickly became tacky.

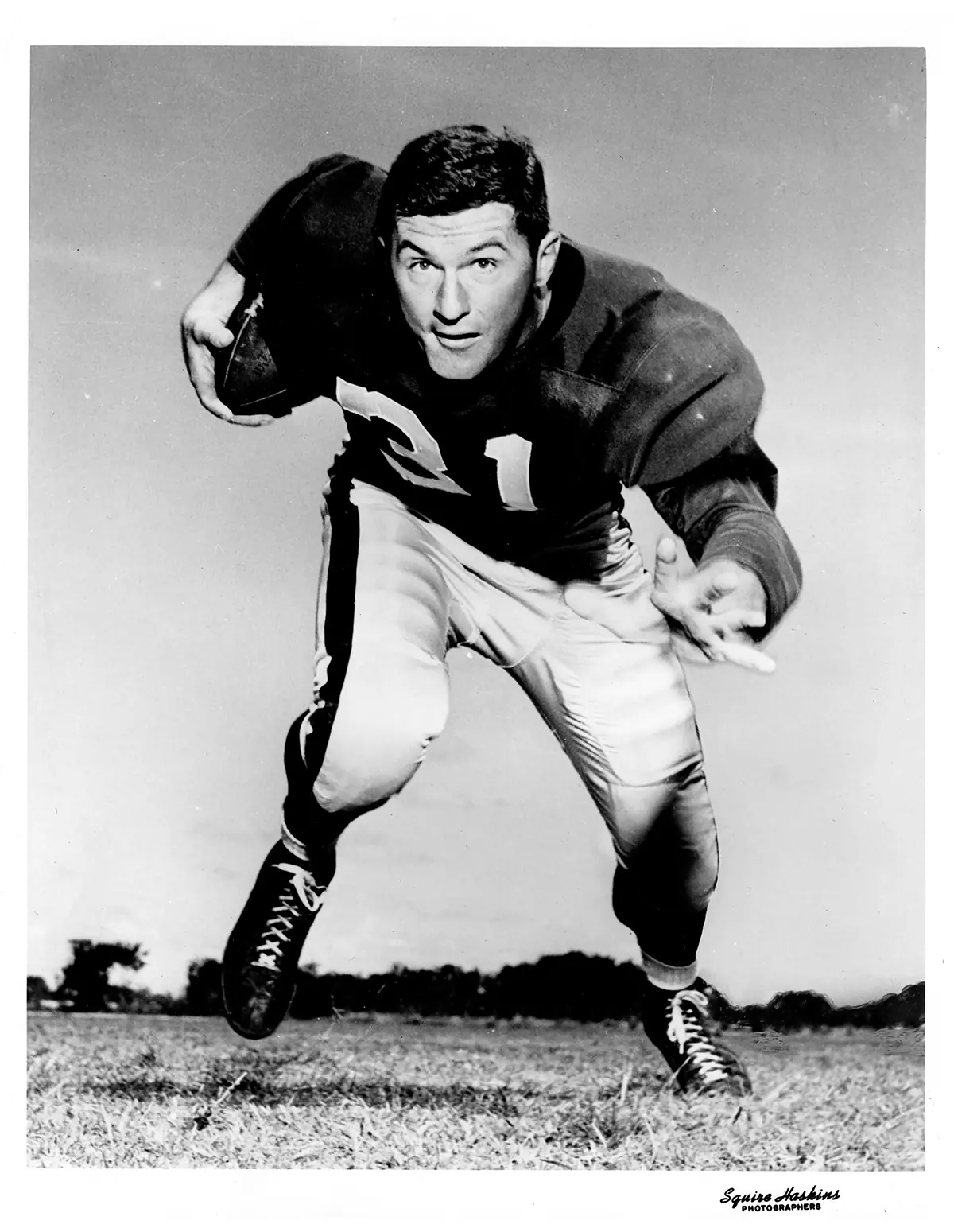

Contributing to all the mad spending, Sanford commissioned a king-sized, framed portrait of Doak Walker attached to the lobby wall over Vaughn’s antique sofa. This unlikely mismatch was located directly adjacent to the framed Certificate of Membership issued by the league.

Next was securing a lease to use Burnett Field, a 10,000-seat minor league baseball park, as the team’s practice site. South of Dallas in the Oak Cliff neighborhood, the grounds were centrally located and close enough to everything. Of course, the team would share the facility with some other occupants. Being close to the Trinity River, rats had set up a base camp in the locker rooms, an unpleasant problem that lasted for decades.

There would be only one option available for the team to use on Sundays, and it would be a good one. The Cotton Bowl was a jewel nestled in the heart of the Fair Park area of Dallas and was only 22 years old, although recent expansions over the previous four years meant that 40 percent of the stadium was practically brand new. Unlike many of its NFL counterparts, the stadium was specifically built for football and could be considered the best field in the league going into the 1952 season. The Cotton Bowl also had plenty of seats, instantly becoming the second largest in the NFL in terms of capacity. The brothers negotiated an attractive deal with the city and Fair Park officials to lease the stadium for a mere fee of $60,000 for their six home games. Having an adequate NFL-caliber facility was one thing that could easily be checked off as completed.

While some observers questioned the league’s decision to place a pro team in an area that was so predominantly devoted to the college game, others questioned the Miller brothers’ sanity. Either way, most saw it as a futile attempt to achieve different results with the pieces and parts that had failed in two other cities.

To help in this matter, many newfangled thoughts on how to market the team were being thrown about. One idea was that during pregame introductions, each Texans player would ride out on horseback. Seemingly not considered was that several of the players had never been on a horse before, or that the horses might soil the field. What could possibly go wrong? Another idea was that when replacement players came in as substitutions during the game, they would run onto the field carrying the Texas state flag, passing it off to the player headed to the sidelines.

For traveling, the Miller wives had planned on outfitting the team in full Western wear with cowboy boots and hats. They commissioned Ripley’s of Dallas Supreme Quality Tailors to design snap-button shirts in the club’s colors with the logo and team name prominently displayed. The balance of the ensemble would come from Fort Worth Stockyard clothing merchants. Onlookers would know who the Texans were, never mind that the team could not play in these “uniforms.”

In late February, commissioner De Benneville “Bert” Bell traveled down for the first of his several preplanned status checks. Originally, he was to spend two working days in town. He would wind up staying longer.

During the offseason, it was almost unheard of for Bell to travel outside of his Pennsylvania base. Traveling to see games during the season was one thing, but afterward he simply did not like to take trips and usually would go no farther than Atlantic City. But for this venture, since creating the Dallas franchise was primarily his own doing, he wanted to take on the added oversight.

With Bell arriving at the railroad station late on a Wednesday night, Giles arranged transportation for him to check in at one of Dallas’ finest locales, the Baker Hotel, courtesy of the team. The next morning, the Millers went to the Baker and met the commissioner for breakfast. There was a Salesmanship Club of Dallas press conference being held there later that morning to announce the sponsorship of a Texans exhibition game with the Detroit Lions. Bell was impressed that the brothers had taken initiative and already made a good football decision that would also benefit local charities. He couldn’t wait to hear what else they had accomplished.

After attending the press conference, Bell wanted to see some of the city, so Giles Miller took him on a drive around town. They went aimlessly through neighborhoods and by area attractions. Their conversation started out strong, as they were able to avoid telephone calls and other interruptions. But while riding along, Bell asked about the plan for other summer games before the final Detroit matchup. Miller told him that he had agreed with Washington just the day before to play in San Antonio at some point. Quickly agitated, the commissioner bellowed, “Fine. That’s two. What about the rest?” Bell let him know that both the Eagles and Steelers had already made all their arrangements.

Given the very short amount of time Miller had been involved with the team, Bell’s question took him by surprise. Although a quick starter, he felt he should not be expected to have everything already laid out like the established teams that had been in the league for years.

For traveling, the Miller wives had planned on outfitting the team in full Western wear with cowboy boots and hats. They commissioned Ripley’s of Dallas Supreme Quality Tailors to design snap-button shirts in the club’s colors with the logo and team name prominently displayed.

As the drive continued, the commissioner then inquired about training camp sites. When Giles responded that he didn’t yet have any idea where they would go, Bell barked, “You should have known from the first outset,” before also adding, “I’ve counted on you being a full-time owner on the job.”

Sensing that their discussion would consistently turn to what he had not done so far, Miller explained that he never considered devoting more than part of his time to the operations of the team, and that he would appoint some fellow board members and staff to become more involved with the day-to-day functions. He wanted to utilize his talents to promote and market.

Bell again voiced that he expected to communicate with only one person in Dallas and that Miller could not perform his necessary duties if he was spending his time on other affairs. The air was tense throughout the afternoon, and Miller felt like crashing the car. After starting the day out so well and attending the press conference, the old commissioner had raised his expectations to a higher level than where they should have been. He wanted seasoned perfection that Miller did not see coming.

Bell’s tough love approach just did not work, at least from Miller’s perspective. He was a beginner. What he really needed was more guidance and less criticism.

After the drive was finally over, the two returned to the hotel where Bell would change his clothes and get ready for the evening. A team-hosted buffet dinner awaited at the Brook Hollow Country Club. Day one had started out with optimism, but ended with criticism.

Day two would bring a tour of Fair Park’s grounds. Having never seen the stadium in person, Bell wanted to get an up close look at the Cotton Bowl. His plan was to wait out the morning at the hotel, working on other league business, and arrive there in the afternoon. This was so that he could personally see how the venue would appear during actual game times. He was more than impressed with the facilities, particularly with the large number of available lower- and upper-deck sideline seats. The Cotton Bowl was completely devoted to football, unlike the baseball stadiums most of the league utilized, which often had obstructed views, bad seating angles, and lacked ample seats between the goal lines. Seeing the Cotton Bowl firsthand was something even the gruff Bell could find no fault with.

Later that evening another dinner event was held, this time at the Mercantile National Bank Building with over one hundred businessmen and professionals in attendance. Once again, however, Bell became critical. He wondered why, with all of this income available under one roof, the team didn’t have any sort of season ticket or sales plan presentation for an event where people received a free dinner that they could have easily paid for. A nondrinking man himself, he huffed, “You’re getting rich people liquored up and not taking advantage of them spending money to help the league cause.” He left the event early while the rest of the party stayed and talked football, enjoying his absence.

By Saturday morning, Bell had decided to stay longer. He went to see the team’s offices for the first time and hoped to spend much of the day discussing ticket policy. After seeing the layout of the Cotton Bowl, Bell wanted to understand what their thoughts were regarding the potential of premium pricing for the side seats of both decks.

Miller was ready for the pop question, but the answer didn’t go over well. He commented to Bell that basically two-thirds of the seats were between the goal lines and would be sold as reserved. It was his intention to set the end zone area prices at half the rate and as nonreserved. All those reserved seats would be the same single price, first come, first serve.

Bell was quick to agree on the end zone discounting while explaining his point of view that those fans provided noise and rang the cash register at the concession stands. Spending less on their ticket, they could spend more on food and drink.

Before Giles could get around to disclosing that the end zones would be primarily segregated seating for African Americans, something that Bell did not know, the commissioner got off on a tangent as to why a seat three rows up on the 50-yard line would sell for the same price as an upper-deck seat midway up on the 20-yard line. He then took a seating diagram and practically set the price for the tickets himself. Miller decided to withhold any further input, accept Bell’s points, and call it a day. He did not follow the bracket-pricing advice, however, instead going with his gut.

Talking civilly wasn’t going to happen. Bell still believed that Miller and company should already know how to run a franchise.

The following day, Sunday, was to be a full board of directors meeting held in the game room of Giles’s home. Bell had already decided to show up and was invited to attend. He had never seen any NFL owner with a residence as large and palatial as Miller’s 20-room mansion.

After listening to the agenda and commentary play out, Bell asked to speak to the group. He expressed his opinion about ticket prices and pointed out the urgency to get sales underway immediately. He also wanted to let everyone know, from his mouth, that a massive opportunity had been missed two nights ago at the Mercantile dinner event.

He went over the key rules of the league and the quirky rules of his own. For someone who was steadfast in his desire to only deal with one person, it seemed odd to Giles that Bell was basically training the Texans staff on how to approach and deal with him. In typical fashion, and with class, Miller let it go and didn’t challenge the loud voice of the league. He bid the commissioner farewell and safe travels, offering Earl Goins to take him to the station. Bell left on a late afternoon train, having put in a full four days of work in Dallas. The visit would be the first time where he would demonstrate his art of micromanaging and criticizing.

After passing the first test with Bell, optimism returned. Whether or not the brothers could be considered visionaries, courageous, fools for punishment, or just plain crazy, they nevertheless remained completely confident and enthusiastic in what they were doing. Giles Miller prophetically proclaimed, “There is room enough in Texas for all kinds of football,” whether it be at the high school, college, or pro level. He also added, “The Texans are going to field a stemwinder of a team next fall.”

This excerpt originally appeared in the September issue of D Magazine with the headline “Nobody’s Team.” Write to feedback@dmagazine.com.