At 11 a.m., the kitchen at Nonna is pleasantly abuzz. In the laboratorio in the corner, the pastas for Julian Barsotti’s four restaurants—Carbone’s, Fachini, Nonna, and Sprezza—are made.

Barsotti pulls out the mill he uses for whole-grain flours. Today he’s making bigoli, a shape whose name is a variation on the Venetian dialect for caterpillar. The shaggy pasta sometimes uses buckwheat, which Barsotti replaces with milled farro.

He pats a well in the flour for the eggs, then swirls and mixes the dough. As he kneads, we talk about the art of slow-cooked ragù and its variations across Italy: the meat ground or pulled, beef cheek or veal shoulder, layered in polenta or poured over pasta. He will never get tired of the translation process.

Over the 11 years since he opened Nonna, Barsotti has tinted pasta with tomato conserva and stuffed it with a delicate langoustine butter. He’s used rye flour in gnocchi and dolloped them with crème fraîche and caviar. He’s made farro with quail and chanterelles, and tagliarini with white truffles and butter.

Always, he operates with one dominant principle: that combining a specific sauce and a specific pasta can produce an epiphany. Eating cacio e pepe in Rome and tortellini in brodo in Bologna convinced him of this.

When he’d only been a cook for one year, Barsotti was thrust into the position of full-time pasta-maker at Oliveto, a San Francisco restaurant where Michael Tusk was a chef. In the early 2000s, Tusk, Paul Bertolli, and (later) Thomas McNaughton were the gods of adding a seasonal NoCal sensibility to traditional, hyper-regional Italian pastas.

“For all of our rolled pasta, we were just using farm-egg yolks, which give it a superior texture to whole egg,” Barsotti recalls. “We also had small mills around for farro and spelt.” He remembers the revelation of hard red winter wheat penne with a pork Bolognese.

He extrudes the bigoli through a hand-crank press, and already we can see how their rough edges will grip the sauce. The pasta will be served with a smashed duck meatball, charred rapini, and an anchovy colatura—a delicious marriage only lasting for a few weeks.

Pasta Types to Know

Extruded

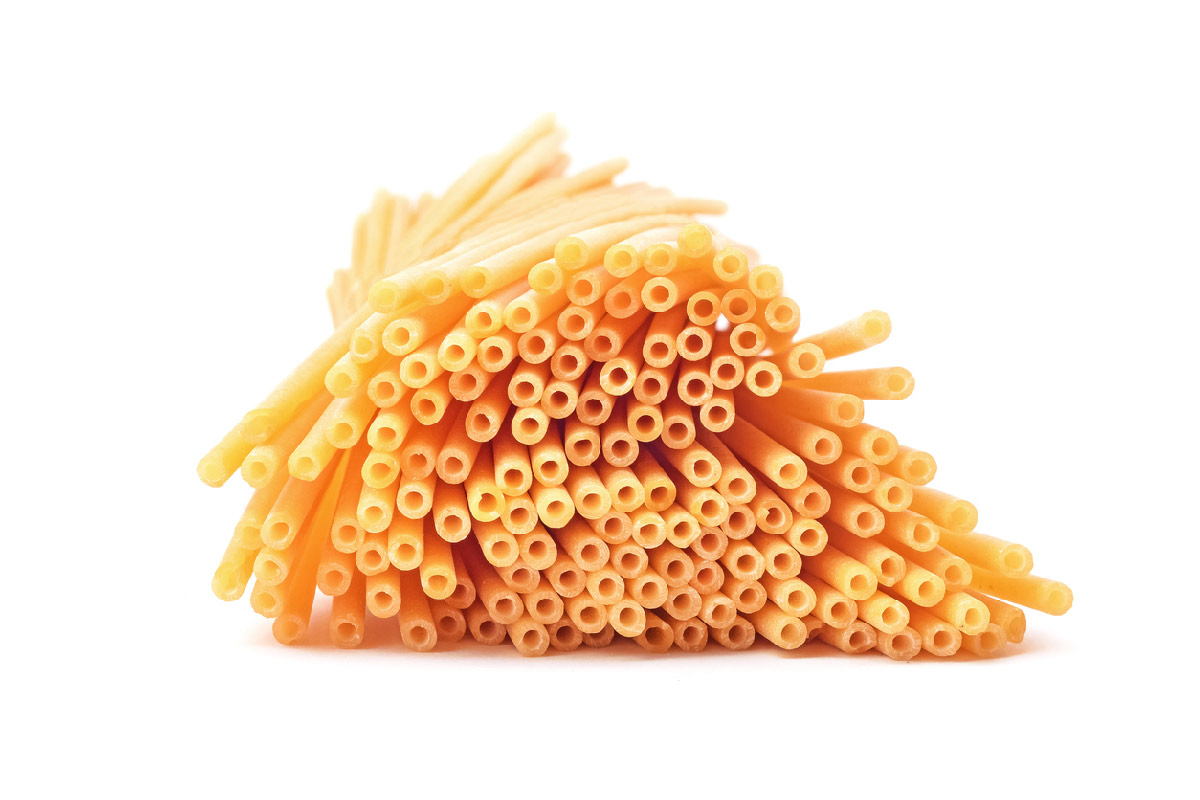

Dough, usually a simple durum-wheat and semolina enriched at times with egg yolk, is passed through a crank fitted with a “die” of a specific shape that produces pasta with particular characteristics of width and shape

Pappardelle—a wide, long ribbon

Bucatini—long tubes, like slightly thicker, hollow spaghetti, with great bite and chew

Fusilli—short, tight twists, shaped like a corkscrew

Filled

Sheets of dough are dolloped with filling, folded, then cut with a cutter or rolling wheel

Agnolotti—parcels folded over themselves, like small ravioli with an extra lip

Tortellini—crescent-shaped parcels, sometimes served in broth

Hand-shaped

Small bits of dough are stretched and shaped entirely by hand

Orecchiette—cupped bits of dough, shaped like little ears

Strozzapreti—short twists (the word means “priest strangler”)

Gemelli—two strands, twisted around each other, joined at the ends